I had a feeling that once I wrote my 2014 e-book Yeah! Yeah! Yeah!: The Beatles and America, Then and Now, published through the good offices of The Daily Beast and Vook e-publishing—and by the way, it’s a genuinely good little book; 45 customer reviews, average 4.5 stars!—that I’d be on the hook for future Beatles anniversary essays.

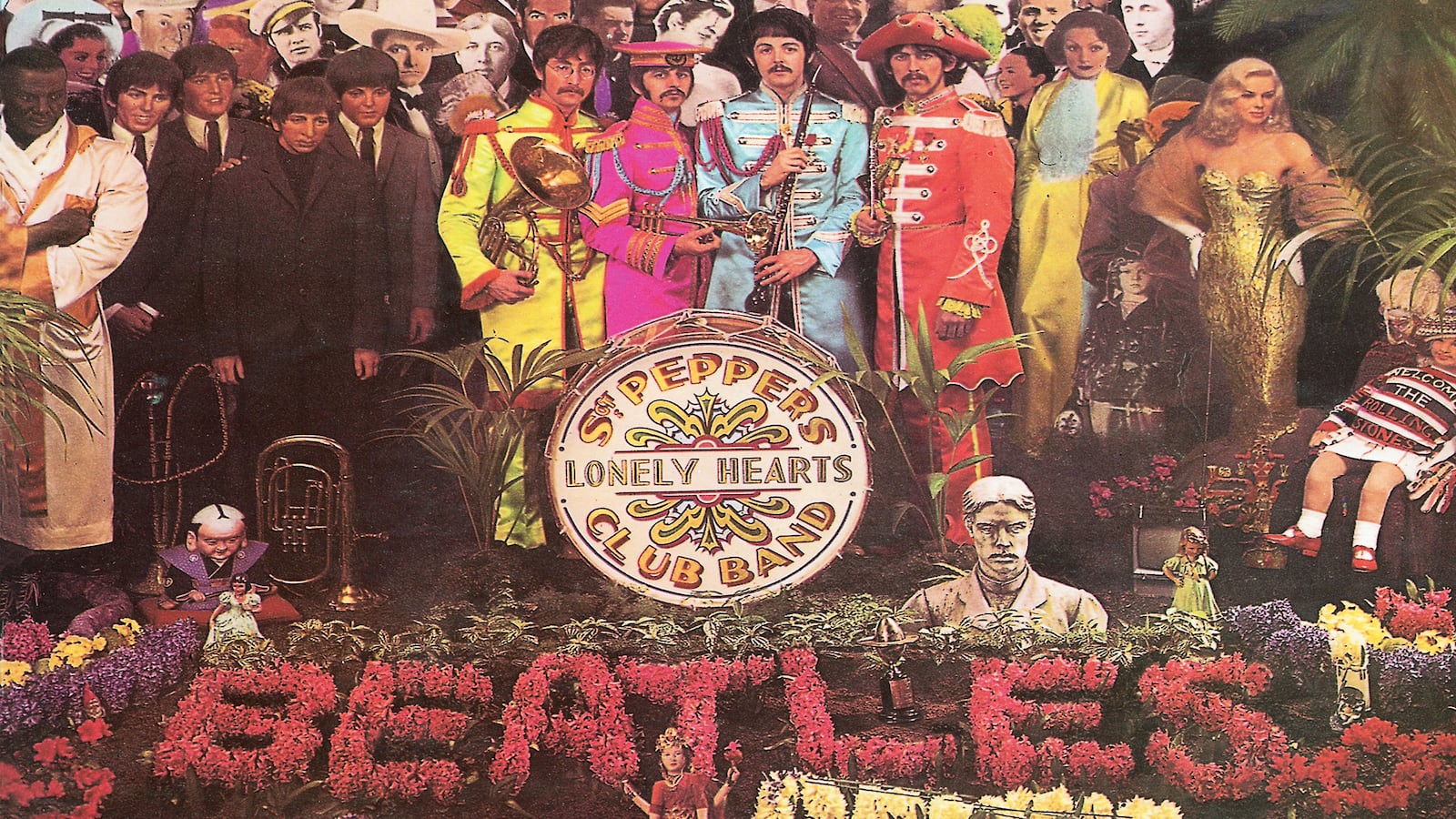

So here we are at the big one: Sgt. Pepper turns 50. Sure enough, my esteemed boss has asked me to weigh in. I’ve thought and thought about this. The normal posture of someone like me would be to play defense. To concede that much time has passed, and maybe it hasn’t worn well, but to plead with readers to understand that in its moment …

That’s the essay I was going to write. But now I’ve had a drink, and I’ve decided to play offense. So here. Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band may or may not be, in your opinion, the greatest album of all time. “Greatest” is subjective. You might think lots of other records are the greatest. You might think Exile on Main Street is the greatest. Or London Calling. Or In Utero. Or Back in Black. Or Back to Black. Or It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back. Or The Fame Monster. Or The Life of Pablo.

I’m not sure that even I think Sgt. Pepper is the greatest album ever; I’m not even sure it’s The Beatles’ greatest album ever. Most days I think that’s Abbey Road. And about 27 days out of any given year, I think it’s Revolver.

But this is an unshakeable truth: If you don’t grasp that Sgt. Pepper is the most important album ever made—well, sorry, you’re just being dense.

And yes, to grasp this, you do have to have a bit of a handle on the times, and that isn’t some big demand on my part. I just published at The Atlantic’s website an essay that uses the occasion of this anniversary not as a celebration of Sgt. Pepper per se, but as a moment to toast the golden age of the vinyl album. In that essay, I trace the history of the record album, which was invented in 1948 almost wholly for the convenience of the classical music fan. When the long-playing, i.e., 20 minutes a side, album was invented, that’s what it was: A way for classical music fans to not have to get up and change sides in the middle of movements, as they had with the old 78s. (And by the way, if 78, 45, and 33 don’t mean anything to you, click here.)

The people who invented the “LP,” as it was called, never imagined that music directed chiefly at young people could make for a coherent work of art. A few other records had sorta-kinda done that—Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde, the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, and Revolver, most notably.

But no one had ever made a record that was designed to be listened to in one sitting as a performance. Anyone who knows anything knows this.

The quality of the songs is ridiculously off the charts. And the subject matter. Yes, the subject matter. That’s what makes it hold up, I think. We know today that songs can be about anything. But back then, songs weren’t about anything. Most pop songs then (as now, come to think about it) were about love. But there wasn’t a love song on the entire record. There were love-ish songs: “Getting Better,” “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” But even they were shifty and enigmatic and full of strange layers.

And the songs that weren’t about love were about … life. “Fixing a Hole” was literally about Paul McCartney fixing the leaking roof in his Scottish country home; but metaphorically, it was about the possibilities and limitations of the human imagination. No one had written a pop song about that before.

And then there’s the big one. “A Day in the Life.” This one’s about no less a subject than existential alienation. I remember watching an episode of American Idol many years ago, in the Simon-Paula-just-go-have-hate-sex-already era. It was the first night they’d secured the rights to perform Beatles songs. Weirdly, they had one of the kids sing “A Day in the Life.” This little fawn who’d been belting out drippy love songs for weeks was suddenly singing a lyric about a man dying in a car crash, narrated by a Meursault-like singer whose indifference is so overpowering that he laughed at the picture of it in the newspaper. The young man was clearly confused by the words he’d been ordered to sing. A deliciously subversive little moment, for the old-fart caucus.

Later verses are as surrealist as a great painting. Four thousand holes in Blackburn, Lancashire. That line came to John Lennon from a news clip about potholes in the roads of said Blackburn, Lancashire, but in his hands the holes became the kinds of things that Magritte or Ernst might have painted, or an image Breton might have incorporated into a poem. And then there’s the whole orchestral build-up. Twenty-four measures (that’s about 15 seconds) for which the orchestra was told: Score? There is no score. Just start on your lowest E and end on your highest E and do whatever you please in between.

OK, I’ll stop there. As for this new Giles Martin-produced mix, I listened to it. I honestly can’t tell any difference. I never could. Stereo, mono. Just words. I’m gratified to see that it’s getting great reviews, but that just isn’t what I listen for. I listen for the joy and intelligence being communicated. If you can’t hear those qualities in staggering abundance on this record, I can’t help you.