Fifty years ago on a rainy April 22nd morning, the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair began with a 45-minute parade featuring a Chinese drum and bugle corps, Montana cowboys, and Japanese geishas among its 4,000 marchers. More than 250,000 people from around the world had been expected to attend opening day—hence the international emphasis of the parade—but fewer than 100,000 came, with only 63,791 of them actually paying the $2 price of admission.

What went wrong on that April morning offers us a window into the hubris of that World’s Fair, but equally important, it offers us a look at what we as country believed a half-century ago—and often still believe—makes us appealing to other nations.

“We went to the New York World’s Fair, saw what the past had been like, according to the Ford Motor Car Company, saw what the future would be like, according to General Motors,” the narrator of Vonnegut’s World War II novel Slaughterhouse Five writes in a passage brimming with sarcasm. By contrast, the science fiction writer Isaac Asimov came away from the fair feeling optimistic about the likelihood of continued peace between the United States and the Soviet Union. “Its glimpses of the world of tomorrow rule out thermonuclear warfare,” he wrote in his predictive essay, “Visit to the World’s Fair of 2014.”

The full story of the fair escapes both writers’ characterizations. The bad weather wasn’t all that kept crowds away from the New York World’s Fair on its opening day. The Brooklyn and Bronx chapters of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) had threatened a stall-in of cars on the highways leading to the fair. CORE was protesting a litany of problems, from job discrimination to slum housing, that affected New York City’s black and Puerto Rican communities, and while the stall-in did not materialize, the threat of it led many to stay at home.

It was not the kind of fair debut expected by Robert Moses, the 75-year-old president of the New York World’s Fair Corporation and master builder of bridges and roads, who had been a key figure in New York politics since 1924, when Governor Al Smith appointed him chairman of the State Council of Parks. Nor was it the last time Moses would be wrong about the fair. He predicted the fair would generate $120 million over its two seasons, leaving New York City with a $40 million profit. In the end New York City got back only $1.5 million of the $24 million it loaned the Fair Corporation, and investors in the fair earned just 62.4 cents on the dollar.

For most of the World’s Fair’s 52 million visitors, neither its opening-day problems nor its failure to turn a profit finally mattered, though. What mattered to them was that Moses had stayed true to his belief, “A fair is everything for everybody from everywhere.”

Visitors entering the 646 acres of the fairgrounds had a variety of sites to focus on as they walked or rode the Swiss cable cars that took them on a five-minute trip 112 feet above the fairgrounds. In the center of it all was the Unisphere, a 12-story, 940,000-pound stainless-steel globe surrounded by three rings designed to indicate space flight. Paid for by the U.S. Steel Corporation, the Unisphere was designed to symbolize the fair’s motto, “Peace Through Understanding.” It did that, as well as advertize U.S. Steel, but unlike the Trylon and Perisphere, which were the undisputed icons of the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair, the Unisphere faced stiff visual competition.

Nearby on the fair’s grand axis was the “Rocket Thrower,” a monumental, 43-foot-tall bronze figure hurling a rocket heavenward with his right hand and reaching for a constellation of stars with his left, and after the “Rocket Thrower” came two more gigantic, eye-catching structures. An 80-foot-tall U. S. Royal Tire, with 24 red gondolas seating four people each, doubled as a Ferris wheel, and in the U.S. Space Park, sponsored by NASA and the Department of Defense, visitors could see the largest collection of American rockets and space vehicles to appear outside Cape Kennedy.

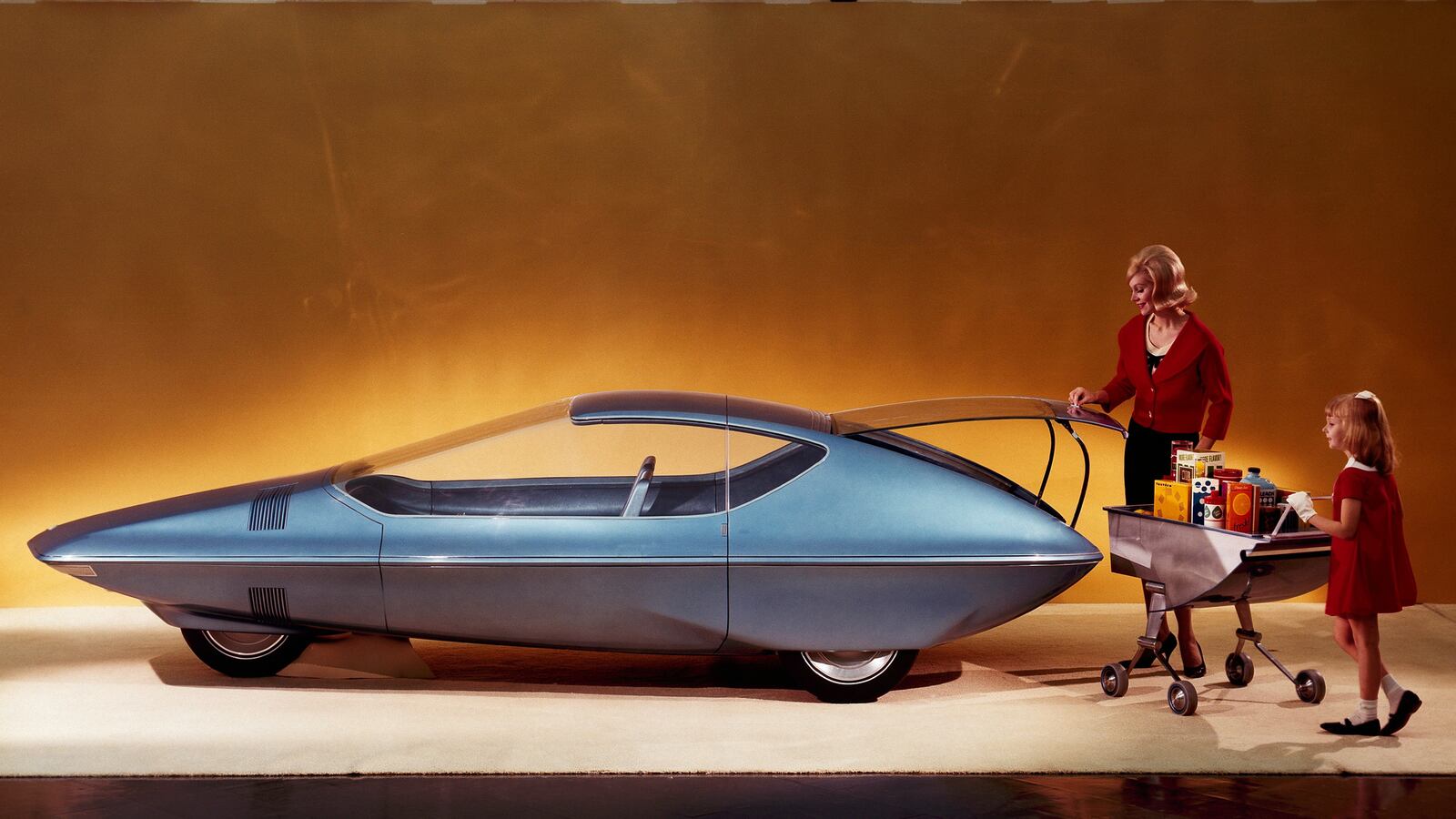

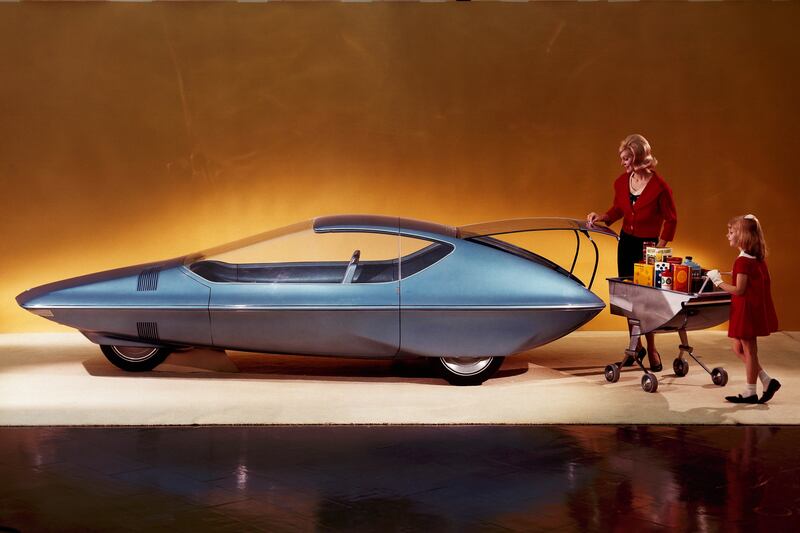

The exhibits in the corporate pavilions that fairgoers waited in long lines to enter were equally eclectic, despite their shared message that here were products everybody should want. The General Motors pavilion, which looked like a plane and came with a tail fin, featured not only a car- and airplane-dominated City of Tomorrow but also a self-propelled “road-builder” five stories high and three football fields long that could tear through the densest jungle forests and produce from within itself one mile of four-lane superhighway every hour.

General Electric’s Walt Disney-designed Carousel of Progress was only slightly less ambitious, taking visitors back in time to family tableaux of the 1890s, 1920s, and 1940s and then ending with the household of the present, in which appliances like the ones GE produced made the good life possible.

At the IBM pavilion, designed by Eero Saarinen, already famous for the swooping concrete curves of his Trans World Airline Terminal at Kennedy Airport, came the most genuinely futuristic exhibit of all—one featuring computers that quickly solved everyday problems, from planning a dinner party to doing foreign language translations.

In a Life magazine essay, “If This Is Architecture, God Help Us,” Yale architecture historian Vincent Scully Jr. threw up his hands in despair at the agglomeration he saw before him and wrote, “I doubt whether any fair was ever so crassly, even brutally, conceived as this one.” But a half-century later, as America struggles with how to define itself in the post-Cold War era, it is more telling to see the fair as a lost opportunity.

This was a time when the United States was vying with the Soviet Union for world dominance—it is tempting to imagine how the fair might have been perceived if, instead of a collection of rocketry, there had been an exhibit devoted to President Kennedy’s Peace Corps; if, instead of a display of GE household appliances, there had been an exhibit on the potential of the still-new birth control pill to shape modern family planning.

In the year the New York World’s Fair opened, the United States was changing in remarkable ways and, for an all too brief moment, free from the dark shadow Vietnam that would cast over the rest of the ’60s. Before the first season of the World’s Fair ended, Lyndon Johnson had begun his “war on poverty.” Congress had passed the Civil Rights Act, and the Beatles had won the country’s heart with their debut on the Ed Sullivan.

For anyone looking in the right places, there was more than enough to celebrate without feeling America was just flexing its muscles.

Nicolaus Mills is professor of American Studies at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Winning the Peace: The Marshall Plan and America’s Coming of Age as a Superpower.