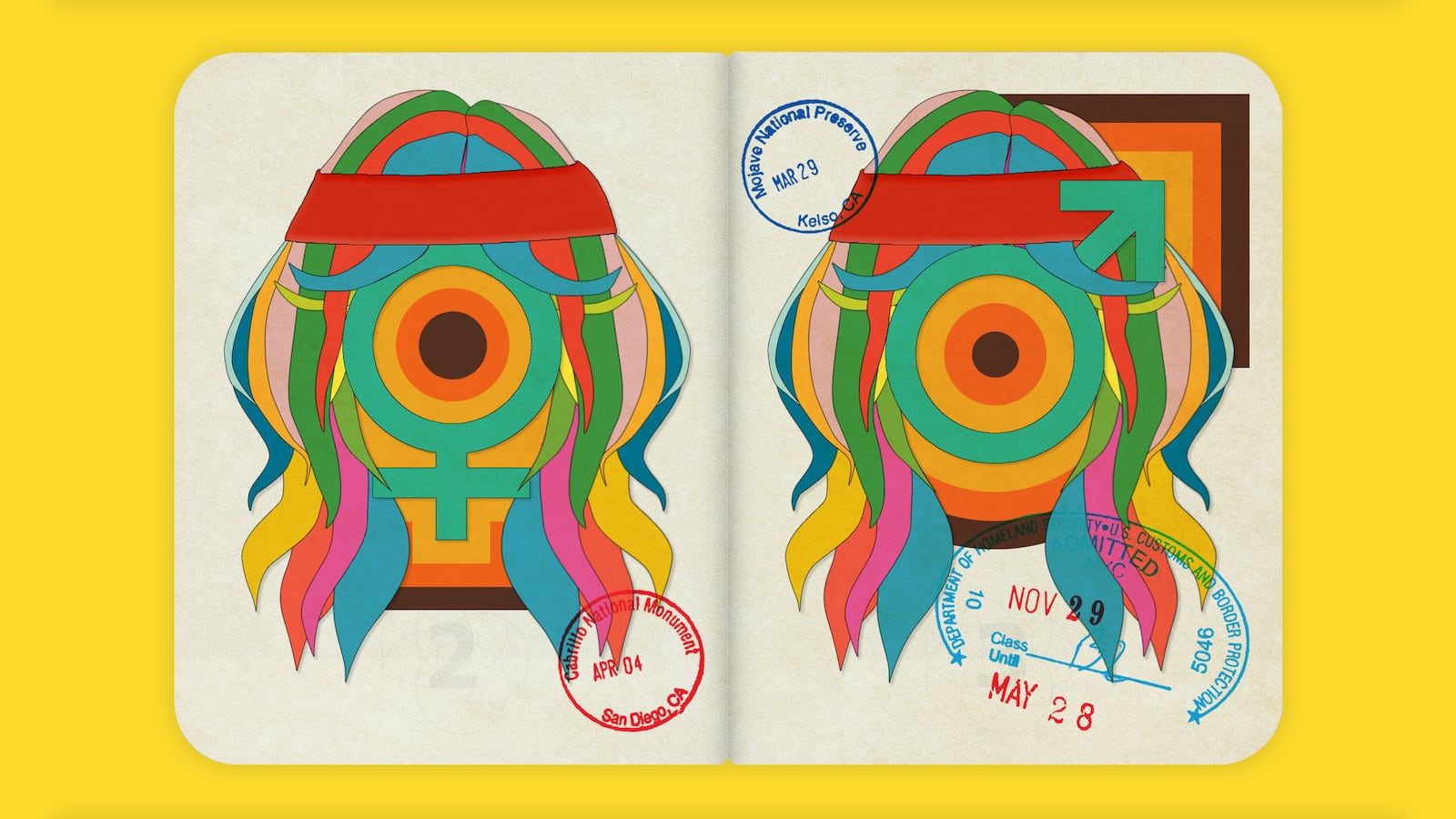

Two simple letters on American passports have recently become the site of immense cultural anxiety: “M” and “F.”

Between the transgender community’s fear that the Trump administration might make it harder to change one’s gender marker from “M” to “F” or vice versa, and a September court ruling ordering the State Department to give a passport to a non-binary intersex person who wants an “X” instead, the sex field has never been under more scrutiny.

But “M” and “F” didn’t always appear on the federal identity document. In fact, sex was not directly listed on U.S. passports until 1977.

According to court documents filed in the ongoing non-binary passport case, the reason gender made its way onto the passport at that time is a fascinating one: the rise of androgyny and unisex fashion in the 1970s is apparently why experts deemed it necessary to include a sex marker.

A four-page State Department memo entitled “History of the Designation of Sex in U.S. Passports” briefly outlines this history.

The agency submitted the memo in U.S. district court as part of its defense against a lawsuit from Dana Zzyym, the aforementioned non-binary individual who applied for a passport by writing “intersex” in the sex field.

As the State Department notes in the memo, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) first assembled “a panel of passport experts” in 1968 to devise recommendations for international standards for the travel document.

“In January 1972, the group agreed to suggest basic standard data elements for passports, including, for the first time, the bearer’s sex,” the memo notes. “This data element was recommended because the experts recognized that, in light of the increasing number of international air travelers, and the rise in the early 1970s of unisex attire and hairstyles, photographs had become a less reliable means for ascertaining a traveler’s sex.”

That recommendation—along with further work from the ICAO panel—led the State Department to begin “the collection of sex data on passport application forms” in 1976 and 1977, making it mandatory by 1978.

A 1974 report from the ICAO Panel on Passport Cards corroborates this account: In a section on the recommended “information to be included” on passports, the report notes that “the box concerning the cardholder’s sex has been included since first names do not always give a ready indication and appearances from the photograph may be misleading in this respect.”

ICAO communications officer William Raillant-Clark told The Daily Beast that records from the January 1972 meeting are not available: “Consequence of the paper age and all the associated archival constraints, I suppose!”

The Daily Beast has asked the State Department’s Bureau of Consular Affairs for more information about that meeting and will update should they provide.

When gender markers first appeared on U.S. passports, they were received by the press as a total non-event, according to Northeastern professor Craig Robertson, author of The Passport in America: The History of a Document.

“In my research, every time there’s a slight change to the passport, newspapers will run what is essentially a State Department press release,” Robertson told The Daily Beast. “When they are changing the passport in 1977, the main newspapers all run a story on it but the headline isn’t ‘Gender Added to the Passport.’”

For example, a Boston Globe article from October 1977 headlined “About passports…” notes that”the sex of the passport holder, to be denoted by the symbols ‘M’ and ‘F,’ will be included for the first time”—but waits until the ninth paragraph to do so. The new, smaller size of the passport book was apparently considered more noteworthy.

That’s not to say that the introduction of the sex marker didn’t have an impact. It certainly affected transgender people, long before they became hyper visible in the media.

It wasn’t until 1992—as the State Department memo indicates—that there was a clear policy for transgender people who needed to change a gender marker, and even then doing so required costly surgery. Not until 2010 did the State Department lift that surgical requirement at the request of then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

Nor was it the first time that passports had communicated gender. As the State Department memo notes, “early U.S. passports” used “masculine and feminine pronouns” in text descriptions, and used “the word ‘wife’” to describe familial relationships.

Before World War I, as Robertson explains to the The Daily Beast, men were expected to be the passport holders for their families—a situation that changed in the 1920s as women began to travel more as individuals.

“The specific category of gender isn’t there, but the passport is used to police gender within heteronormative and dominant heterosexual ideas,” said Robertson.

In the 1920s, pictures fully replaced text descriptions of a passport holder’s physical appearance—and it was society’s faith in the photograph’s relationship to “truth” and “objectivity,” Robertson says, that made a separate gender marker seem completely unnecessary.

“The assumption is that the photograph must be a reliable source of identity,” he told The Daily Beast. “There’s so much confidence that gender can be read easily off the body that it’s not on the document directly. It’s not even discussed.”

Robertson added that in all the archival material he consulted for his book, “there was not one mention that I found—in the documents I could get my hands on—of gender.”

It apparently took an era of unisex names, long hair, and gender-bending fashion to prompt passport experts to decide that the photograph could no longer be trusted to indicate a passport holder’s sex.

As the Atlantic noted in a 2015 history, 1968 marked the start of “the unisex movement” within the fashion industry and from there, the trend spread out to the broader public through roughly the mid-1970s before the resurgence of more conservative dress in the 1980s.

The fact that sex markers would show up in the passport during this precise time, Robertson says, “makes perfect sense,” given how the document tends to change during moments of cultural shift.

“Once the passport emerges, changes in what information is on there seem to me to always respond to moment of anxiety when, suddenly, what are viewed as these set and natural categories are revealed to be problematic, and revealed to be introducing uncertainty,” he told The Daily Beast, explaining that the introduction of a category like “sex” helps the government maintain authority over a passport holder’s identity.

“When the body becomes less than reliable—according to the standards that the government wants—they can go to the document.”

But it’s still not clear why the government had to know the sex of passport holders, as U.S. District Judge R. Brooke Jackson wrote in his Sept. 19 ruling in favor of Dana Zzyym. The State Department has long been fighting to avoid issuing a non-binary passport to Zzyym, and so far Judge Jackson is not persuaded by the agency.

In his most recent ruling, Jackson reviewed the State Department memo—including the detail about unisex attire leading to the introduction of binary sex markers—and then noted that “this still doesn’t answer the question of why a traveler’s sex needed to be ascertained,” especially because ICAO standards have since changed.

Indeed, the ICAO has been much more flexible than the U.S. State Department when it comes to gender on passports: According to the agency’s most recent specifications for machine-readable travel documents, sex on a passport is “to be specified by the use of the single initial commonly used in the language of the State where the document is issued,” meaning, in the United States, “the capital letter F for female, M for male, or X for unspecified.”

In 2012, the ICAO even reviewed whether or not gender should still even be required to be displayed on travel documents, concluding “at this stage” that it’s more important to keep the requirement in place despite several potential benefits, like increased comfort for “transgender passengers” and a decreased data collection burden for offices that issue travel documents.

Ultimately, though, the ICAO concluded that cons like the financial cost of changing “border control software” outweigh those benefits for the time being. (The report concludes by mentioning that “the mandatory requirement” might still change “in the future.”)

Raillant-Clark told The Daily Beast that the ICAO has recently “received a lot of inquiries about ICAO standards pertaining to gender markers in travel documents.”

“We are pleased that the wider community is interested in ensuring that travel documents are respectful of everyone’s gender identity or lack thereof,” he said.

The State Department, on the other hand, is still “reviewing [Judge Jackson’s decision] and consulting with the Department of Justice,” as The Daily Beast previously reported, rather than announcing they will expand the binary gender marker policy.

That stance raises an interesting question: If it was ICAO that prompted the State Department to put sex markers on the passport in the first place, why hasn’t the State Department fallen in line with ICAO’s new recommendation that there should be three sex marker options?

“The Department does not explain its departure from adherence to this standard,” Judge Jackson wrote in his ruling.

What will happen to passport sex markers remains to be seen: The State Department could continue to refuse to allow an “X,” potentially triggering a Supreme Court case down the line. Perhaps sex markers could disappear altogether.

But from a historical perspective, it is perhaps only fitting that the very letters used to police the transgender, intersex, and non-binary travelers of today were first introduced to police gender fluidity during another era of cultural upheaval.