There is a consensus among Western leaders and strategic thinkers about how to respond to Russia’s brutal and unjustifiable aggression against Ukraine. Unprecedented and sweeping economic sanctions, moving NATO forces toward its eastern frontiers, and providing substantial lethal aid to Ukraine are the pillars of this response.

While this approach may not be sufficient to stop Russian forces from seizing Kyiv, Kharkiv, and other cities, it has already aided Ukraine in slowing Russian offensives, and should be useful in supporting a protracted Ukrainian insurgency against the Russian occupiers. If the will to maintain economic pressure on Russia remains strong enough for long enough, it could also create real incentives for Russia to negotiate and, perhaps, to withdraw.

But in the next few days, it is already clear that Russia is going to increase its pressure on Ukraine. Its tactics—which have already included indiscriminate missile and artillery attacks on civilian centers and the use of prohibited weapons, including cluster and thermobaric munitions—will grow even more inhumane. The civilian toll will rise. In all likelihood, it will rise greatly.

ADVERTISEMENT

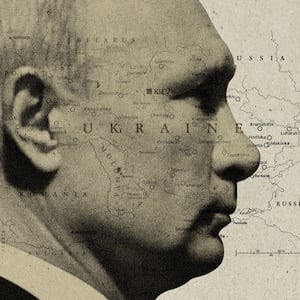

Vladimir Putin, frustrated with his progress to date, sensing what he must do next and anticipating the Western response, has prepared the ground for his stepped-up attacks by rattling his nuclear saber. He has asserted that he has put his “defensive” nuclear forces on alert. Earlier, he made reference to what he asserted would be the unprecedented costs should NATO or others step in to try to stop his invasion of his democratic neighbor.

His goal was to forestall any consideration of NATO putting troops on the ground to stop him or of introducing any other military efforts to counter his onslaught, such as air attacks. His warning was effective. Western leaders have ruled out no-fly-zones or other approaches that might be both difficult to implement and carry with them the risk of triggering “World War III” or a devastating nuclear exchange.

So pressure to do more is likely to grow even as the options for doing more have been severely limited.

Not only does this situation create real, deep conundrums for Western planners and profound unease for the otherwise brave defenders of Ukraine, it raises real long-term questions.

Ukrainian security forces accompany a wounded man after an airstrike hit an apartment complex in Chuhuiv, Kharkiv Oblast, Ukraine on February 24, 2022.

Wolfgang Schwan/Anadolu Agency via GettyNotably, if the conclusion from this war is that nuclear-armed states have the ability to do whatever they want to their neighbors, however cruel and unjustified, because the risks of fighting back against them are too high, the world will not be left a safer place.

Consider for example, Putin’s calculations regarding further reconstituting his warped vision of a Russian empire if he were to feel that NATO’s Article 5 guarantees—that all members will come to the aid of any member who is attacked—were actually just a paper tiger. Would he feel that he could roll his tanks into Latvia without fear of being challenged because so many Western leaders consider the threat of nuclear war too high to ever challenge him?

Will NATO—at the moment its renaissance is being celebrated—actually reveal to its principal adversary that it is not really up to the job for which it was intended?

These are not easy questions to answer. The risks of nuclear war are as real as they are ghastly. But the risks of giving all the world’s Putins the license to run roughshod through their neighborhoods are also, as history shows, profound.

Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman, former National Security Council (NSC) director for European affairs, said to me, “Western governments are terrified of Russia’s nuclear saber-rattling. We’ve lost our nerve in the face of shallow threats.”

Tom Nichols, a long-time professor at the U.S. Naval War College and writer of the “Peacefield” newsletter for The Atlantic, framed the situation in the following way: “The war in Ukraine is brutal and horrific. But none of that is an argument for a plunge into the abyss.”

But, Nichols cautions, “We are all suffering from the ‘CNN effect,’ watching this devastation in real time. It’s hard not to be emotional about it—I am—but a NATO intervention would be the greatest gift Putin could ask for and risks catastrophic consequences."

Russian President Vladimir Putin visits the National Space Centre construction site in Moscow on February 27, 2022.

SERGEI GUNEYEV/SPUTNIK/AFP via GettyWhat options do we have?

Lt. Gen. Doug Lute, former U.S. ambassador to NATO and former deputy U.S. national security adviser, recommends: “We should focus on anti-armor Javelins and anti-air Stinger missiles, getting as many as possible as fast as possible into the hands of Ukrainian forces and setting up resupply networks in Poland and Romania to sustain the effort over time. These are easy to transport and distribute, relatively simple to use and have already proven effective against Russian forces. We should be stockpiling these now and providing truck transport that can be handed off to Ukrainians at the border. We should take steps to ensure communications for the Ukrainian regime with secure digital comms, including satellite access. The ability of the leadership to communicate is crucial to holding together the military and the civilian resistance.”

Lute emphasizes that now is the time to take such actions while Russia’s attentions are focused away from the western part of the country—the ones that border the EU—and where a long-term resistance is likely to be based. He also advises that more of the private sector should be mobilized (as has happened with recent energy company and airline efforts to pull out of Russia) and that we continue to “pay attention to the flanks” by cultivating the engagement and support of potential new NATO members like Finland and Sweden.

On my Deep State Radio podcast this week, former U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Bill Taylor added that the U.S. could provide more forms of technical assistance like helping the Ukrainian Air Force counter Russian jamming of their radio frequencies, providing Multiple Launch Rocket Systems (MLRS) while we still can get such larger weapons systems into the country, and considering new sanctions like those targeting Russia’s oil sector. (Canada has just announced energy sector sanctions against Russia.)

People crowd the Kyiv train station platform to catch trains to Poland or to places in the western parts of Ukraine on February 28, 2022 in Kyiv, Ukraine.

Chris McGrath/GettyBut what do we do about the moral hazard associated with caving in to Putin’s nuclear gamesmanship? The former NSC senior director for arms control and nuclear proliferation in the Obama White House, Jon Wolfsthal, said: “Putin’s threats are designed to shield him from US/NATO response while he takes conventional action against Ukraine. While abhorrent, it has been clear all along that we were not going to commit troops to Ukraine for a variety of reasons, including the risk of nuclear war (President Biden is 100% right on that). I don’t think [Putin] will use nukes, knows it would be suicide, and not clear his military would support that action.”

Wolfsthal continues, “I don’t agree that failure to send troops or ‘defend’ Ukraine adds to the danger that he might roll into a NATO state. I believe that he is very well-aware that any kinetic move against NATO territory would trigger a full Article 5 response. This is one of the reasons he has moved against non-NATO states and why is he so adamant that Ukraine not join NATO. He knows he would never be able to reabsorb it into greater mother Russia. His attack has united NATO in a remarkable way. And it has shown NATO states that they can be strong and protected without making nuclear threats. And it shows how extreme and unhinged making nuclear threats are.”

Joe Cirincione, a distinguished fellow at the Quincy Institute and nuclear non-proliferation expert and advocate, observed, “Nuclear weapons are praised by most theorists as providing stability, as keeping the peace in Europe. But here we have Putin using nuclear weapons as a shield to wage conventional war—the kind of war in Europe nuclear weapons were supposed to prevent.”

While he concurs our current strategies are effective and may define the limits of what we can and should do and while he also does not believe Putin would attack NATO, after the conflict, Cirincione argues: “After the war, we will have a brief window to discuss not just what our policies should be going forward but to examine what went wrong with our policies in the past. This was not supposed to happen. Either the invasion or the nuclear risks. So, why did it? What could we have done better? I think we have to go back to the 1990s and examine our policies for NATO expansion (Should we have moved so quickly? Could we have reassured Russia more fully?). But also on the nuclear front.”

In a recent article, Cirincione cited a 2007 warning from former Secretaries of State George Shultz and Henry Kissinger, former Defense Secretary William Perry, and former Sen. Sam Nunn, that “unless we moved step by step to reduce and eventually eliminate nuclear weapons, we would “be compelled to enter a new nuclear era that will be more precarious, psychologically disorienting, and economically even more costly than was Cold War deterrence.”

Cirincione says we are now “in that world.” He adds: “If we assume that there must be a diplomatic termination of this war (it is possible that it could end with a palace coup against Putin but I wouldn’t bet on it), then we are going to have to offer Putin some face-saving way out. We are going to have to address his legitimate security concerns (and he does have some).”

Among the suggestions he favors are, “pulling our 100-150 tactical nuclear weapons out of Europe in exchange for reduction in his force, restoring the ban on intermediate-range nuclear weapons that ended when Trump tore up the INF treaty, getting rid of the pointless missile interceptors and silos we deployed in Poland and Romania that Putin fears could be used to house offensive nuclear weapons… getting real about the ‘strategic stability talks’ to include immediate, deep reductions in nuclear forces, making mutual declarations to never use nuclear weapons first and making that the international nuclear gold standard all states should follow, [with] mutual steps to reduce the alert levels of nuclear forces by taking them off hair trigger alert and (as some already do) taking the warheads off of the delivery vehicles.”

Lute says, “Before Putin backs down, he will double down.” That is certainly true. But a growing consensus is that if the U.S. and our allies maintain our resolve and our unity and by ratcheting up existing measures rather than taking steps that risk escalation, in the end Putin and the Russians will likely have to withdraw from Ukraine without having achieved any of their major goals.

That may not come soon. The cost to get to that outcome may be horrific. But fortunately, the X-factor backing up all these measures from the U.S., NATO, the EU, and allies worldwide is the courage and the commitment of the people of Ukraine. Whatever advantage Putin may have in terms of military hardware, that is not something he can replicate or, it increasingly appears, defeat.