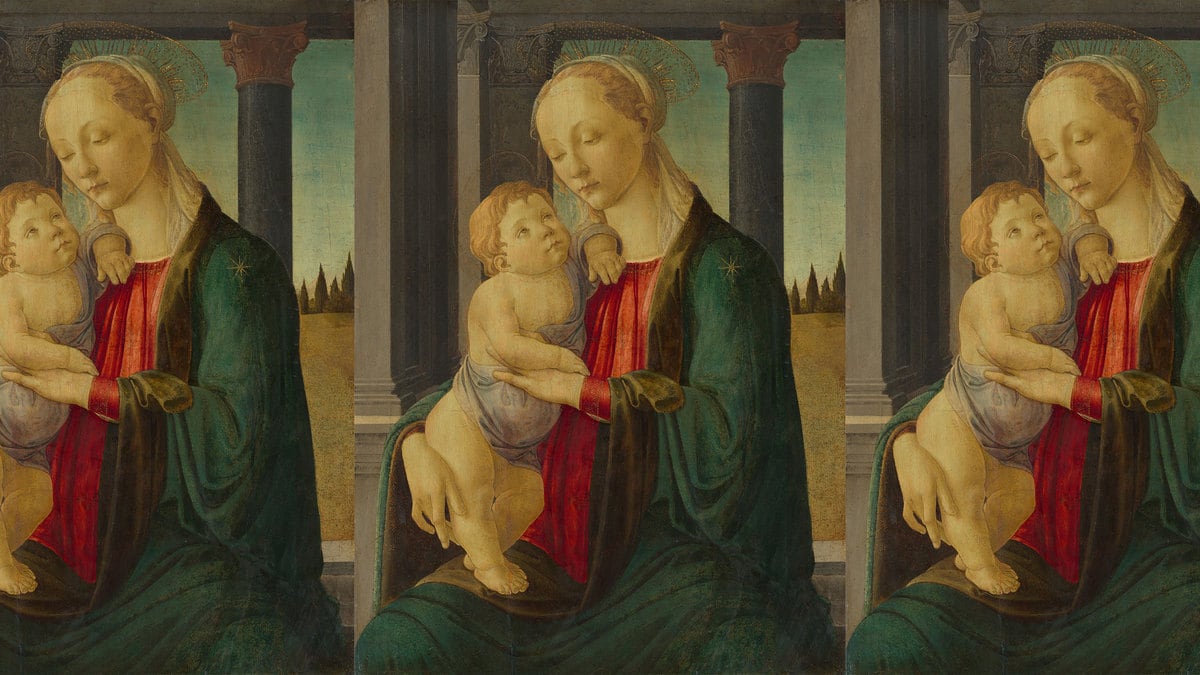

ROME—The last time anyone was slated to see Italian Renaissance master Sandro Botticelli’s 1485 Madonna and Child painting was at an exhibition in 2007 in the now shuttered New York art gallery owned by super-grifter Lawrence Salander. This was a few years before Salander was sentenced to six to 18 years in prison for defrauding famous clients—including John McEnroe and Robert De Niro’s artist dad—of around $120 million. (He’s now whiling away his time on Rikers Island after pleading guilty to 29 counts of felony fraud.) Salander’s rap sheet also includes stealing art and heirlooms from the estates of Stuart Davis and Dr. Alexander Pearlman, and secretly reselling them for his own profit.

The exhibition that was to showcase the Botticelli—called “Masterpieces of Art: Five Centuries of Painting and Sculpture”—never opened on its October 2007 inauguration date because federal marshals raided Salander’s swanky Upper East Side gallery a few days earlier, seizing thousands of artworks, including the Botticelli, and locking up the shop. Salander went to jail and his lawyers were left trying to settle up with his creditors and determine who really owned around 4,000 pieces of art he had sold. During the lengthy trial, Earl Davis, the son of modernist painter Stuart Davis, who lost around $2 million in art Salander stole and sold, told the court, “Had I been robbed at gunpoint or by a thief in the night, it would have been preferable to the ruthlessly drawn-out torture that he inflicted upon me.”

The battle for the assignment of Salander’s assets to pay off his many debts is still raging, but the fate of the Botticelli was determined in 2014 when New York judges ruled that it should go to the Panama-based offshore investment company Kraken Investments, for reasons that remain more than a little murky.

Last week, the European Investigative Collaborations consortium of journalists, which includes the Guardian, sifted through a trail of claims tied to trust company La Hougue, based on the Channel Island of Jersey, which is an offshore dependency of the British Crown, making it a convenient tax haven.

There they found a cache of inconsistencies in Kraken Investments, an affiliate company, including the fact that its owners, Canadian siblings John Dick II and Tanya Dick-Stock, had no idea they were named as owners of the company until about a year ago. Dick-Stock famously sued her father, John Dick—who has lived in Jersey for more than four decades—in March 2020, accusing him of pilfering the considerable family fortune to deny her and her brother millions. The elder Dick said instead that his daughter was “wholly unreliable.”

The investigation into La Hougue found that most of its clients were Dick’s associates. A report by the journalist consortium claims, “Among them were, for example, the Denver owner of sexually-oriented entertainment resources nicknamed Porn King, Edward Wedelstedt, convicted of extortion and tax fraud, and Israeli art dealer Ronald Fuhrer, who owned a painting by Botticelli. Some Russians are also found among those who used the services of La Hougue.”

This Botticelli is thought to be the missing 1485 masterpiece, and it has a rather peculiar provenance even without its disappearance after Salander’s arrest—including having been once owned by Imelda Marcos. Fuhrer, who runs the Golconda Contemporary Gallery in Tel Aviv, did not respond to numerous messages and attempts to reach him. But a person who answered the phone at the Tel Aviv gallery—now closed over COVID-19 concerns—said that he thought the Botticelli was in Kraken’s Panama warehouse, though couldn’t be sure it wasn’t in a Jersey mansion.

The La Hougue document dump included several receipts tied to the Botticelli, according to the journalist consortium. Among them was an invoice to Fuhrer—who was divorcing at the time— from Richard Wigley, for the creation of documents which were not specifically identified on the invoice. Wigley was later investigated for fabricating documents, though not necessarily those related to Fuhrer.

The La Hougue documents also include a receipt for $2.2 million for the sale of the Botticelli to Kraken, noted as an asset to cover a loan Fuhrer had taken from the company for unknown reasons. Der Spiegel, which is also part of the investigative journalist consortium, approached Fuhrer with the theory that the sale of the Botticelli was faked to ensure Fuhrer’s soon-to-be ex-wife couldn't claim it in the alimony settlement. Fuhrer never responded to the requests for comment.

Fuhrer did, however, tell Artnet News in December 2014 that he had personally received the Botticelli on behalf of Kraken Investments after they spent around $2 million in litigation to prove they owned it. “My advice would be to try to sell it,” he said at the time. “If a painting gives you such trouble—in this case, such unheard of trouble—that means that it wants to go away, maybe it’s not supposed to be.”