When the stress of Sehar Aqeel’s job led her to consider harming herself, she jotted down a note on her iPhone: “If anything ever happens to me, it was because of L’Oréal.”

Aqeel, who worked at the personal care company from August 2017 to March of this year, alleged in a series of Instagram posts that her time there was filled with toxic work conditions that led her to debilitating burnout, suicidal ideation, and hospitalization. Her claims were first reported by the beauty industry watchdog account Estée Laundry.

As a sales rep and woman of color, Aqeel says she was subjected to daily “microaggressions” from her white supervisors and colleagues. She says one boss referred to themselves as a “slave driver,” and a senior manager had a habit of speaking about her weight in front of coworkers. “One actually said during a meeting, ‘Sehar, you melted,’ because I had lost weight,” she told The Daily Beast.

Certain managers would make comments about how others were dressed, Aqeel said, and some “had a reputation of making people cry at work.” Late nights were normal for Aqeel, and every day she would bring pajamas into the office. She never slept at work, but it was normal for her to stay until 10 p.m. or 11 p.m., so she changed into comfier clothes once everyone left.

Aqeel’s former coworkers all agreed that she was a hard and exceptional worker who consistently met management’s goals. (They also confirmed the pajama story.)

Aqeel, who tells more of her story below, isn’t alone. Since her allegations went public last month, 50 anonymous people came forward to Estée Laundry detailing their negative experiences working at L’Oréal. L’Oréal Group owns brands such as Lancôme, Giorgio Armani Beauty, Kiehl’s, Garnier, and Maybelline.

The Daily Beast spoke with seven people who worked or currently work at L’Oréal and shared similar stories of a detrimental work environment. Some of their complaints, like long hours and abrasive bosses, sounded typical of any large conglomerate.

When reached for comment, L’Oréal put forth additional employees who wanted to counter the claims and speak about their positive experiences at work. The Daily Beast spoke with three of those workers. All of the people who spoke to this reporter—including the satisfied staff—asked to remain anonymous.

Matthew DiGirolamo, L’Oréal’s chief communications officer, declined to comment on the specifics of Aqeel’s case “out of respect for the privacy and sensitivity of this individual’s personal situation.”

In a statement, DiGirolamo added, “We have done everything in our power to address her concerns, prior to her leaving the company. At all points, we have acted with this former employee in accordance with our Ethics process and with Canadian Law and we strongly disagree with her qualification of the events.”

When asked what steps were being taken to protect employees’ mental health and work/life balance, DiGirolamo wrote, “The well-being and professional satisfaction of our employees is very important to us, and we’re constantly working to assess this.”

The communications officer also noted that every year L’Oréal sends employees a survey that is conducted by a third-party research firm called Pulse. Last year, 92 percent of workers completed the questions. “The engagement level scores of L’Oréal employees (which measures motivation, pride and level of recommendation) is industry leading—with a 78 percent favorable score, some 8 points above the norm, while additionally the enablement level (which measures how well employees feel supported and enabled by their manager and the organization as a whole) has an overall score of 70 percent positive, some 3 points above the norm.

“In 2020, 90 percent of employees felt that they are ‘treated with respect as individuals,’” DiGirolamo added. “We use the feedback from this survey to improve our policies, programs and practices. As we are a company of more than 85,000 employees with 167 different nationalities operating across 150 countries, we know our work of creating and sustaining a workplace in which everyone can experience personal and professional fulfillment never ends.”

The Daily Beast also gave L’Oréal a chance to respond to the employees’ stories below. The company declined to comment on individual accounts, but said in an email: “While these anonymous accounts being reported are impossible to corroborate, we are always open to listening to and learning from the experiences of every current and former employee. We are disappointed when anyone has a negative experience at the company and work actively to understand any serious allegations and address any behaviors that do not meet our ethical standards. We are committed to hiring, developing, and promoting people of all identities, cultures and backgrounds and to maintaining an inclusive workplace. Our priority is to build supportive and safe environments for all the members of our teams worldwide.”

“L’Oréal and my burnout finally broke me”

Aqeel’s story is not the first time allegations of questionable practices at L’Oréal have surfaced. Last year, workers expressed concern when they were mandated to return to their offices in July. At that point, the coronavirus pandemic had surged towards a deadly second wave and a working vaccine was still months away from hitting the public.

Five L’Oréal employees told CNN their managers told them that they would put them on a “noncompliant” list if they refused to come back in, and feared their jobs would be in jeopardy.

The company contended, “L’Oréal's plan to cautiously return employees to worksites is guided by one fundamental principle: to protect the health and safety of our employees. Being together is a key ingredient to our culture and essential to the success of our business in a creative industry. As such, we have gradually returned employees to offices in locations around the world under a comprehensive safety plan only when permitted by local governments.”

In Aqeel’s case, she told The Daily Beast she was promised a promotion, but it never came. She says she had an “anything for the company” mentality; when management noticed negative reviews of the workplace on Glassdoor and “hinted” that “it would be helpful if [L’Oréal] had more positive comments,” Aqeel wrote a glowing one, though she says that deep down, she had some reservations.

Things changed after the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin in June 2020. L’Oréal, like all brands, fumbled to find a meaningful way to respond to the cultural reckoning.

A British transgender model named Munroe Bergdorf called the brand out after it posted a graphic on Instagram in support of Black Lives Matter.

“You dropped me from a campaign in 2017 and threw me to the wolves for speaking out about racism and white supremacy,” she wrote, referencing her short-lived stint as the first trans model in the UK to front her own L’Oréal campaign. Her tenure ended in controversy, when the Daily Mail accused her of “racism” after the tabloid unearthed posts Bergdorf wrote on Facebook saying that whiteness was “the most violent and oppressive force of nature on Earth.” L’Oréal fired her for posting “hate speech.”

“There was a whole discussion internally and I couldn’t believe how long they took to make a statement about it,” Aqeel said. “Internal employees said we needed to address [Bergdorf’s claims], and it took a few days for the CEO to finally put out a comment and statement.”

Eventually, L’Oréal announced it hired her to serve on its newly formed UK Diversity & Inclusion Advisory Board. The model said in a statement that she considered the new gig a “reconciliation.”

But this came off as performative to Aqeel, who noted that she was still being treated the same by her white bosses despite the brand’s online posturing. She spent the first week of global BLM protests exhausted, and was not her usual cheery self at work. In one Friday meeting, she says a manager told her to “take some time this weekend” to relax.

“I thought it was easy for her to say that,” Aqeel recalled. “I can’t take the weekend off. I have to live through it. I lived in Chicago during 9/11. I was nine years old walking home from school with my 6-year-old sister getting screamed at to go back to my own country, that I didn’t belong here. I didn’t understand why people were yelling at me for the color of my skin, so it really affected me when I saw George Floyd’s daughter saying she didn’t know why she was treated differently because of the color of her own skin.”

Aqeel said she brought up her feelings to a manager, and said she did not think L’Oréal was meeting the moment. The manager, who was white, allegedly responded, “I have friends of color. I know how you feel.” Aqeel said that in that moment she knew she needed to take a break from the company. She went on disability for six months, citing burnout.

Aqeel lost four pounds during her first week of leave. She’d been trying to lose weight for a year, and finally hit her goal after being inside, depressed, crying, and refusing to eat. “I didn’t want to lose those final four pounds that way,” she said.

But eventually the time off helped her work on better coping mechanisms and link up with a therapist. She returned to L’Oréal at the end of the year.

Almost immediately, her workload picked right back up to unbearable levels. Aqeel said she worked about 56 hours a week without getting her promised promotion. She felt “gaslit” because she did her job well but received no appreciation from her bosses.

“I didn’t recognize myself anymore,” she said. “I wasn’t smiling, I was so pessimistic and I wasn’t happy. This wasn’t me. I spent the entire lockdown alone by myself and that didn’t break me. But L’Oréal and my burnout finally broke me.”

Aqeel filed a complaint with HR about her bosses’ behavior and L’Oréal hired an external mediator to launch an internal investigation. As it went on, Aqeel began her second disability leave in mid-February. By March, the company informed Aqeel that her claims were “unfounded.”

The investigation also found that “[her] behavior may represent a risk to the psychological safety of other employees.” According to the investigation, Aqeel did not attend one of her year-end meetings and that counted as “insubordination.”

Aqeel told The Daily Beast that she did attend her first year-end meeting, but would not attend the second unless it was recorded or a woman of color was present. (The Daily Beast viewed emails written after the meetings where Aqeel reiterated she had made those two requests to HR.)

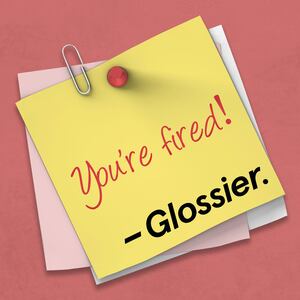

Ultimately, Aqeel was fired. As HR put it in their email, “Your actions have irreparably broken the bond of trust that is of central importance to the continuance of the employment relationship,” the email alleged.

Aqeel says no one from the company has reached out to her since she went public with her allegations. Three of Aqeel’s former coworkers, who asked to remain anonymous, corroborated her exceptional work ethic and the verbal mistreatment she says she endured.

A week after getting fired, Aqeel was on the phone with Sunlife, her insurance company. The customer service representative told her that the company had denied her disability claim. Aqeel said she felt “overwhelmed” during the phone call, and mentioned that she had thoughts of suicide. She made clear to The Daily Beast that she wasn’t threatening to harm herself on the call, but since she blurted out her ideation the customer service representative sent police to her apartment.

The cops asked her to come to the hospital for a welfare check, even though Aqeel says she was in the company of a close friend and did not need to go. She spent about five hours waiting in the hospital until a doctor discharged her after speaking to her family members and therapist on the phone.

If you or a loved one are struggling with suicidal thoughts, please reach out to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741

Aqeel has filed a complaint against L’Oréal with the Committee on Standards, Equity, Health, and Safety at Work in Montreal. A representative for the labor board did not respond to The Daily Beast’s request for access to Aqeel’s complaint by publication time.

Four months after leaving L’Oréal, Aqeel said that she feels “a weight being lifted off” of her shoulders. “They just make you feel like you’re the one in the wrong,” she said. “[By posting about my experience] I didn’t want to harm L’Oréal. I just want to help somebody else who might be feeling the same way, so they don’t feel alone like I did.”

Aqeel’s case isn’t the only one that has led to legal action. In 2018, a former vice president of marketing at L’Oréal named Amanda Johnson filed a lawsuit against the company claiming she was fired after complaining about race, sex, and disability discrimination at work. L’Oréal denied the allegations, which according to accusations Johnson made in court documents included stories about “sex-fueled” parties at European hotels during business trips and accusations that her boss watched porn during a business meeting. The case is ongoing.

“The people who were mean were the people who got promoted”

One former employee who spoke with The Daily Beast said the working environment at L’Oréal was “especially abusive.” Three used the word “toxic” to describe a culture of non-stop stress they said prompted mental health issues which stemmed from their treatment at L’Oréal. All of the employees expressed a fear of retaliation for speaking out, even if they no longer worked there.

One former global creative director based in New York said they worked such extreme hours—around 7am to 4am the next morning—that they would sometimes sleep in their car instead of heading home for the night.

“I would keep a change of clothes in my car, and sleep one or two hours and go back to work,” the worker said. “When I was hired, we were promised Summer Fridays. But those did not exist, and we spent Saturdays and Sundays working.”

The three L’Oréal current employees who enjoy their jobs all reported having Summer Fridays. One of them, based in New York, said that sometimes she’ll use that time to finish up work or hop on a quick call. “But generally, I have every other Friday off,” she said.

Another employee based in the United States said that her supervisors are “very aware” and supportive of providing a work/life balance. “I’m very vocal about the time I need to handle an issue at home,” she said. “I might not be at work for a few hours, but I’ll make up the work at a later time. We have certain policies where supervisors don’t do meetings early in the morning or late in the evening to respect our different [home] schedules.”

One New York employee said that she’s seen L’Oréal’s human resources department take steps to address worker malaise through its “Simplicity Project.” She was a member of the team, where staff can opt-in to meet with human resources, survey their colleagues, and discuss ways to improve work culture.

“The Simplicity Project has been quite successful for as long as I’ve been in the group,” she said. “We got a flexible work schedule directly because of feedback in that team. Prior to those discussions, our policy was work from home two days a month. Now you can do it two days a week.”

But another New Jersey-based employee who left L’Oréal this year and also took part in the Simplicity Project told The Daily Beast that she remembers the initiative as ineffective.

“We’d do a yearly, company-wide survey to see what the biggest issues and obstacles were, to figure out ways we could improve things,” the worker said. “What stuck out to me was that the biggest thing people complained about there year-over-year was people were doing good work and not getting promotions. Instead the people who were the loudest people in the room—the most toxic people there—seemed to be the ones who were elevated.”

People also reported feeling “burned out and super stressed,” according to the employee. “It felt like when we would review those things and come up with solutions, it fell on deaf ears,” they added. “They’d set up ‘no meeting Fridays,’ but it was never enforced. Just something they did for show. Ironically, the Simplicity Team was a huge time commitment, too.”

The same worker remembered getting “reamed” by a boss during a busy conference call because they did not answer an email that was sent at 10 p.m. the previous night. “They would just make you feel like you had dropped the ball when that’s unreasonable,” the former employee said.

Working from home during the early days of the pandemic didn’t help ease expectations. “People knew you were home, so you didn’t have an excuse to not answer emails or phone calls, no matter when that was,” they said. “I was so stressed and breaking out in hives. I had really bad anxiety and went on anxiety meds for the first time in my life.”

The employee said that near the end of 2020, enough people complained to HR about burnout that some executives began adding disclaimers to their email signatures that said, “Even though I work at all hours, you’re not expected to.”

The worker claimed, “You are 1000 percent expected to.”

“I wouldn’t say I have to answer emails,” another New York employee provided by L’Oréal countered. “My team and the partners I work for have a transparent [relationship]. If something is sent outside of working hours, I’m going to answer when it is working hours. I have personal boundaries, like I don’t have email notifications set up on my iPhone.”

One former executive assistant remembers feeling deflated on their very first day with the company. Right after signing their offer letter, the assistant attended a “Fireside Chat” where employees aired their grievances in a meeting with executives.

“It didn’t seem like anyone was happy or treated well,” they said. “There were no concrete steps to make things better, and that made me feel nervous. I remember telling my mom that night that I felt like Ariel signing away her voice—that’s how I felt when I signed that offer letter. It was a bad feeling.”

As an executive assistant, the worker was tasked with mainly administrative work. L’Oréal bosses referred to it as “low value work.” According to the employee, the phrase was used in a derogatory and “belittling” way by higher-ups.

“They’re constantly talking in meetings asking, ‘How can we reduce our low value work and give the executive assistants more of it?’” the executive assistant said. “I remember one time my boss had a project of hers that she wanted me to work on, and she asked, ‘Would you like some real work?’” the former employee said. “Everyone saw my tasks as beneath them.”

Early into the job, the executive assistant attended goodbye drinks at a nearby bar for a departing colleague. It was after work hours and people were in party mode, but her boss stormed up to her and “shoved her phone” into the employee’s face. An upcoming flight had been canceled and needed to be rebooked. In front of everyone, she says her boss said, “Prove you’re a good employee and fix this.”

The worker remembers getting laughed at by her boss and she fumbled with the phone. “In the future, she’d continuously reference the incident in front of others as if it was a funny memory, but I found it horrible,” they said, adding, “It’s like if The Devil Wears Prada wasn’t fiction, except they had better clothes.”

One former VP said that it was commonplace to see people crying at work or running to the bathroom holding back tears. “There was a culture at L’Oréal where you were rewarded for being harsh,” they said. “The people who were mean were the people who got promoted.”

Another L’Oréal employee who spoke up for the company said that in nearly seven years there, she had been promoted five times.

“It was difficult for me to understand the culture because I’m not from America, I’m Latina and an immigrant,” she said. “Initially I felt like I didn’t know if it was the right culture for me.” She alleges that one of her early bosses at the company asked that she not speak Spanish at work. The manager, who only spoke English, said they were worried that the worker might be gossiping about her.

“Initially I didn’t see a lot of people like me—I saw a lot of French people or European people,” the worker said. “My first two years, I did not know if I should stay. L’Oréal is not for everyone. You have to be resilient, take initiative, and be proactive. Work-wise, it’s very demanding.”

The worker stuck it out and says that things have improved for her in the past four years. “I feel like a lot of [bosses] were coached and had the ability to understand that the way they were acting was not going to make them successful,” she said. “Other bosses couldn’t [adapt] and left. I feel that people can speak up a lot more now.”

“I haven’t had the experience where I was disrespected because of my race,” one employee of color told The Daily Beast. “I am impressed with my ability to be involved in different branches of the diversity and inclusion programs, which is a good way to connect with people I can relate to and have conversations that feel very comfortable and safe. I’ve been in listening circles where we talk openly about race… We use the term ‘microaggression’ in training to educate people on how it can be a subconscious thing.”

“A L’Oréal Baby gets the culture of being vicious and winning at all costs”

There is another type of person who seems to get promoted by management within the company: the so-called L’Oréal Baby.

Workers who spoke with The Daily Beast all knew what this meant: employees who get plucked right out of college and are groomed for success. They rise through the ranks quickly and effortlessly. And, as most of the workers said, they’re usually white men or women.

“A L’Oréal Baby gets the culture of being vicious and winning at all costs,” the former VP said. “These are the people who squeeze and kill the little guys. For many of them, this was their first job and all they ever knew. They’re favored.”

A New York employee who has been with the company since she graduated college considers herself a L’Oréal Baby, but she doesn’t take much stock in the label. “It just means someone who’s started and grown up in the organization,” she said.

The self-proclaimed L’Oréal Baby added that she thinks Aqeel and other online allegations are “sad.” “You feel not great to see that,” she said. “But it’s certainly not representative of the experience I’ve had with the group. I think it seems quite extreme.”

The employee added that one of her goals on the Simplicity Project is to “modernize” L’Oréal’s offices. “The workplace of 10 years ago is vastly different than the one we want today,” she said.

DiGirolamo, the L’Oréal spokesperson, said in a statement that L’Oréal Babies “is a term used informally by some L’Oréal employees to express their pride in the fact that they have been with the company from the start of their careers. It is not an official designation given or tracked by the company. Workers stay at the company “for an average of nearly 14 years.”

Things did end for the former employees who told The Daily Beast that they quit after L’Oréal pushed them to breaking point. A New York employee said she did not work for a year-and-a-half after leaving the company because she suffered from racing thoughts and insomnia. “You can get damaged if you stay in the company for a long time,” she said. “I had to heal myself emotionally and physically and mentally.”

Others described feeling disillusioned with the beauty industry in general after seeing how one of its biggest names operated. “They run the place like it’s like an ER,” the former executive assistant said. “But it’s just makeup at the end of the day. Because of L’Oréal I no longer have aspirations in the corporate world. I don’t care about a title or money. As long as I’m not like these people, I’m very grateful.”