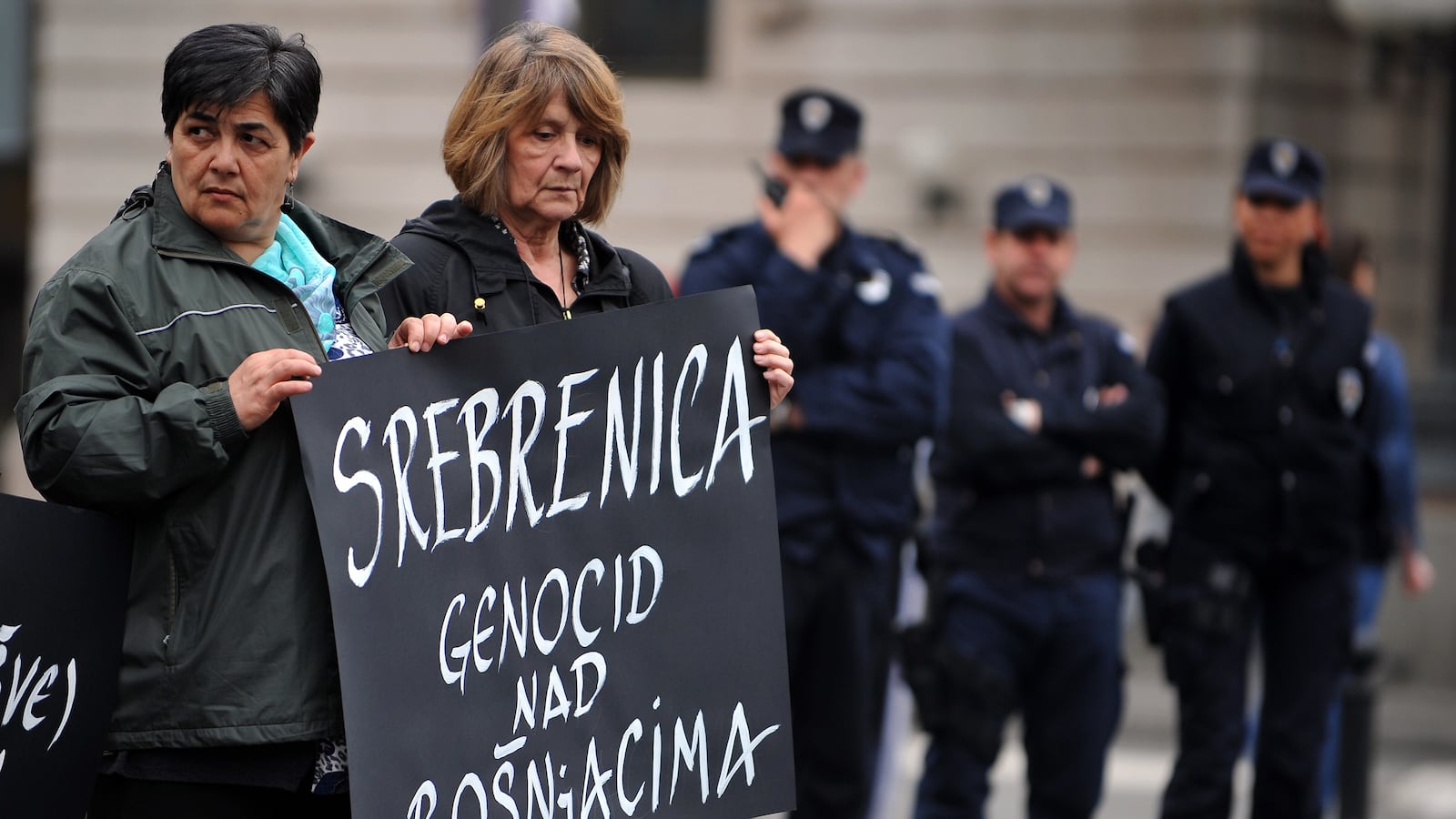

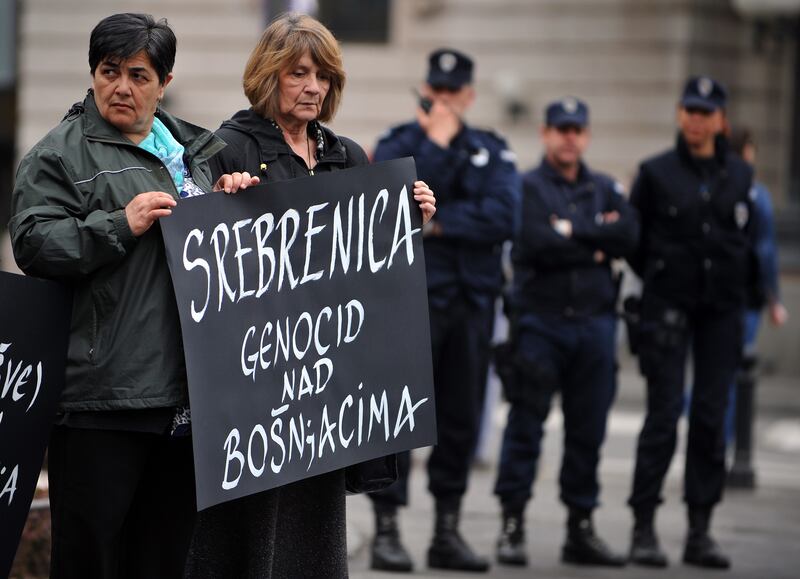

Every time I hear about a massacre like last Friday’s in Houla, Syria, I think back to Srebrenica, the July 1995 Bosnian massacre that helped turn me—and many other post-Vietnam era journalists and policy types—into liberal hawks. Since then, humanitarian intervention has become a recurring feature of American foreign policy debates. After the disasters of Iraq and Afghanistan (no, they weren’t humanitarian interventions but they have sapped America’s capacity and stomach for war), I’d have thought discussions of humanitarian intervention might go the way of the dodo bird. They haven’t. In fact, the debate over intervention in Syria sounds a lot like the debate over intervention in Libya, which sounded a lot like the debate over intervention in Darfur, which sounded a lot like the intervention in Kosovo, which sounded a lot like the debate over intervention in Bosnia.

Understanding these debates requires understanding that they’re really four-sided affairs. There’s the liberal hawk position, which advocates humanitarian action regardless of whether it extends the frontiers of American power. Think Samantha Power. There’s the neoconservative position, which tends to support humanitarian action because it extends American power, since neoconservatives believe it is mostly American power that makes liberal ideals possible. Think John McCain. There’s the anti-imperialist position, which sees armed humanitarianism as immoral because it extends American power. Think Noam Chomsky. And there’s the realist position, which sees armed humanitarianism as unwise because it detracts from American power. Think Brent Scowcroft.

For liberal hawks, making humanitarian intervention happen requires winning support from both other nations and from neoconservatives, two groups with diametrically opposed desires. Other nations will support humanitarian intervention if they believe it is not a vehicle for extending American power. Neoconservatives will support humanitarian intervention if they believe it is a vehicle for extending American power. For other nations, UN Security Council approval is crucial because it limits America’s ability to make humanitarian war serve its own ends. For neoconservatives, UN Security Council approval is dangerous because it limits America’s ability to make humanitarian war serve its own ends. What other nations liked best about the war in Libya was that America “led from behind,” which was exactly what neoconservatives liked least.

I suspect that we’ll increasingly see the same dance play out over Syria. To get Russia’s support in pushing out the Assads, the United States will need to find ways of limiting America’s influence over a new Syrian regime, which is exactly what neoconservatives oppose. Asking Vladimir Putin for help, declared McCain, is evidence of “a feckless foreign policy which abandons American leadership.”

Therein lies the rub. For neocons, “American leadership” is a good in and of itself. There’s little recognition that American leadership might ever be bad for America and for the world, just as there’s little recognition on the anti-imperialist left that American leadership might ever be beneficial. The Obama administration, which is largely an alliance of liberal hawks and realists, is trying to figure out how to exercise enough American “leadership” to pressure Russia into dumping the Assads but not so much that Russia fears Syria becoming an American client. Whether that effort will work is anyone’s guess, but the idea that America can be more effective when it restrains its power via international cooperation—as the US did when it helped establish NATO and when it forged international military coalitions in the Gulf War and the Balkans—makes a lot of sense. Self-limitation can be a tricky concept to defend at home. Then again, as in the days of the Balkan wars, most Americans aren’t paying attention anyway.