Hunter Biden’s plea deal on Tuesday immediately triggered Republicans who cast the no-jail-time agreement as a gross case of judicial favoritism. Democrats quickly shot back that, by facing consequences at all for not filing his taxes and possessing a gun for two weeks while he was on drugs, Biden was indeed receiving special treatment—just not the type Republicans were accusing him of.

The reality may be somewhere in the middle. But regardless of whether his punishment fits the crime, federal prosecutors in Delaware are once again illustrating the very real gray area that applies to the nation’s firearm laws.

The particular gun charge the feds brought against Biden—a drug user in possession of a firearm—is rarely brought as a standalone crime, especially now that roughly a fifth of the country uses cannabis—with an inevitably significant overlap with the nation’s estimated 80 million gun owners. When the feds do bring this type of case, they come down hard. But it’s usually a tool they use to take down tough to arrest criminals, like militant white nationalists, Islamist terrorists, or narcotraffickers.

Hunter Biden is none of those. And that situation is leaving former federal agents, prosecutors, and gun industry experts scratching their heads.

To some, it reads like favoritism.

“I don’t want to throw the book at people. And I don’t want to sound like I'm a Trumper. But this strikes one as really very specially favorable treatment,” said former FBI special agent David M. Shapiro, who now teaches at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

To others, the mere fact that the feds brought this case at all indicates something of a compromise by Delaware U.S. Attorney David C. Weiss, a Trump-era holdover who stayed on the case to minimize the appearance of political meddling. It’s a “sensible bargain,” as Los Angeles Times columnist Harry Litman put it.

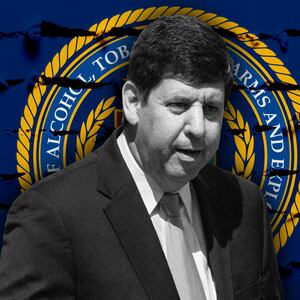

“I don’t see it as him getting some free pass. He's admitted to a serious gun charge, and this diversion process is typical for someone with no criminal record or no backstory that suggests the only way the community can be safe if he's incarcerated,” said former ATF agent David Chipman. “This seems absolutely legitimate, and he's taking responsibility.”

Either way, it shows just how much discretion prosecutors have when targeting gun owners—and presents a question about whether it’s time to stop stripping drug users of their Second Amendment rights.

“The gun debate is a little schizophrenic,” said Konstadinos T. Moros, a California attorney who advocates for wider access to firearms. “The older NRA crowd is very much against drugs and thinks those people are dangerous, always. The younger people, ‘gun culture 2.0,’ most of us have tried cannabis and some actively use it. For most of us, we know it's no different than alcohol. You shouldn’t be armed when drinking, but it doesn't mean you can’t have guns at another part of the day.”

Moros currently represents the California Rifle and Pistol Association in an effort to abolish the state's magazine capacity limit and handgun roster law, but he has also monitored the nationwide push for decoupling the war on drugs to firearms access.

“It's ironic, because Joe Biden has repeatedly defended his son as having done nothing wrong. If so, he should quit defending this law in federal court,” Moros said.

In the United States, a person must pass a background check when buying a gun from a licensed shop. And that includes a federal questionnaire that asks, among other things, if you’re “an unlawful user of, or addicted to, marijuana or any depressant, stimulant, narcotic drug, or any other controlled substance.” Answer truthfully, and you’ll get denied. Lie, and you break the law.

Hunter was caught in a maelstrom of his own making: His 2021 memoir, Beautiful Things, described how he struggled with addiction and was sometimes high on cocaine “every 15 minutes.” During the very same time period, he bought a .38-caliber Colt Cobra revolver that later got on police radar when a girlfriend chucked the gun into a dumpster. Although he only had it for 11 days in October 2018, that short time still overlapped with his drug usage—meaning he almost certainly lied on the ATF form when buying the handgun.

On Tuesday, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Delaware filed single-count information charging Biden with 18 U.S. Code § 922(g)(3). In a separate letter, prosecutors also indicated the existence of a second information charging him with two separate counts of belatedly filing his taxes.

In both instances, they’re wielding a hammer that rarely gets slammed on everyday Americans. The IRS estimates that roughly 10 million people each year don’t file their taxes. Only a small percentage of non-filers are ever charged—and even fewer ever get jail time. The fact that those tax charges are coming back to bite Hunter at all is evidence that the Justice Department is treating him as something different than the average Joe.

But that special treatment may also be at play with the gun charge, albeit in a different way.

In their letter, the feds said Biden will get pretrial diversion on the gun charge, essentially letting him off the hook. He’ll be subject to a program that the Department of Justice reserves for what it calls “opportunities for treatment, rehabilitation, and community correction.”

As a result, Biden could face stiffer penalties for the tax charges, but the DOJ letter is telegraphing that the gun issue is essentially going away.

However, that situation presents an odd result, because the mere fact that they’re charging him shows rare aggression—while, at the same time, letting him go with a warning leaves him better off than others who’ve faced the same charge.

“It's reflective of a compromise, a decision to make this go away and deal with it expeditiously, undoubtedly in light of political circumstances—including who his father is,” Shapiro said, noting that the criminal charge “is subject to a 10-year term of imprisonment. That's not the kind of charge where you'd put somebody in pretrial intervention. That would be for lesser felonies.”

Feds often use the drug-user-in-possession-of-a-gun charge as a fallback for punishing a hard-to-nail criminal when evidence of other crimes is scant. The FBI has wielded it against Neo-Nazis and motorcycle gangs, usually in an effort to get at a wider conspiracy.

Legal scholars and former federal investigators told The Daily Beast that this type of gun charge is normally used to pressure defendants into striking a deal, a method for squeezing information out of them and locking them away with a short stint in prison. It’s not something prosecutors drop, only to apply a slap on the wrist for a tax crime.

“It's usually reserved for somebody that's a real problem in the community—and when that's the only thing we can get them on,” said one ex-ATF agent. “We can jumpstart gang cases, guys selling rock on the corner. You get them on (g)(3), then you start flipping people.”

Years ago, CNN profiled how the FBI orchestrated an elaborate sting operation to ensnare a depressed Michigan pizza delivery guy and actively guide his suicidal thoughts toward violent ISIS martyrdom. That violent terrorist attack never happened, and eventually, what appeared to be a terrorism case against Khalil Abu-Rayyan really just came down to two counts of drug user in possession—all because he was pulled over by a Detroit cop for speeding and found with four plastic bags of marijuana, sleeping pills, and a revolver in his old Buick Century. A federal judge sentenced him to six years in prison, and Abu-Rayyan served most of it before his release in 2020.

On Tuesday, Abu-Rayyan told The Daily Beast that while the president’s son was clearly getting handled with kid gloves, at least the feds weren’t overreaching.

“I do feel like there's special treatment,” Abu-Rayyan said. “My past self would say that's not fair. But it's a step in the right direction… why don't we go after the mass shooters acquiring AR-15s and AK-47s and arsenals, rather than people with simple possession?”

That thinking represents a growing sentiment in younger gun owners, who have increasingly advocated for looser restrictions—and dropping the drug screen altogether. Those calls have grown as states continue to decriminalize marijuana, because federal law enforcement keeps cracking down on pot users with guns in those jurisdictions.

“Feds have been clear that even in states that legalize marijuana, it's still illegal federally, and you're not supposed to have a gun,” said Dru Stevenson, a professor at South Texas College of Law Houston who has conducted extensive research on firearms. “Some states give people medical marijuana cards, and I've talked to people who got a medical marijuana card, so they couldn’t pass a background check to buy a gun anymore.”

Drug-user-in-possession is usually just one of a litany of other charges, so it’s hard to find an exact parallel to Hunter’s case. The Department of Justice only files 200 or so cases a year nationwide where this crime is the only charge, Stevenson said.

“It's rarely a standalone charge,” Stevenson said. “Partly that's because of how police find out someone has a gun, like a drug bust or drug-related violence.”

It’s made even more rare because of how vague the situation can be, and when someone buys a gun versus when they used illegal drugs.

“You get into philosophical questions like, ‘I was a drug user until yesterday,’” Stevenson said.

This particular gun law has been on the books for 37 years and has received widespread support from firearms enthusiasts and gun control advocates alike. While the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Bobby Kennedy brought about the first serious restrictions in 1968, the narco crime wave of the ’80s led to the 1986 Firearm Owners Protection Act that prohibited drug users and undocumented people from passing necessary background checks. The law got little pushback in the decades to come.

Unlike other laws—like restrictions on silencers that can dampen the sound of a shot, or short-barreled rifles that are easier to swing around in tight spaces—it hasn’t been controversial in traditional gun circles.

The National Rifle Association, in an effort to avoid further gun control, has vociferously demanded that the government simply enforce the laws like this one that are already on the books. The NRA has firmly stood against the idea of drug users owning guns, evident by its support for a law enforcement effort called “Project Exile” that involves dragging low-level gun possession cases into federal court to snag stiffer penalties, something that NRA CEO Wayne LaPierre Jr. commended in The Wall Street Journal in 2008. “Leave the good people alone and lock up the bad people,” LaPierre said.

But an effort to push back against the law preventing a drug user from owning a gun is, in fact, in the works.

This month, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals concluded that lifetime gun bans like a Pennsylvania law prohibiting non-violent felons from having guns were unconstitutional. In February, a federal judge in Oklahoma sided with a medical marijuana dispensary employee who had a gun in his car when he got pulled over by a cop. And just last month, a federal judge in Texas dropped the drug-user-in-possession charge against a woman when she wrote that “the government has failed to carry its burden to demonstrate that § 922(g)(3) is ‘consistent with the nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.’”

The drug question on the ATF form—when answered honestly—ranks as the third-most-common reason that firearm purchases get denied in the United States, according to the most recent figures from the DOJ’s Bureau of Justice Statistics. Of the 179,587 gun purchases and permits that got denied in 2018 because of failed background checks, 11 percent of those rejections came from drug use or addiction. But given the widespread use of drugs in the United States, it’s clear that few people actually answer that question honestly. Drug use might be a top reason for rejections, but they still made up only 19,523 of the 16.7 million applications that were screened that year.

“We have to use discretion with these charges. There has to be some danger to the community. We just don’t have the resources to charge everyone who violated this,” Chipman said, recalling his years in the field as an ATF agent.

Federal prosecutors also stack this particular charge with other conduct, even when it’s relatively minor. In 2006, DEA agents searched a Missouri man’s home and found two bags of what appeared to be marijuana, which the man said was for his personal use. But they still nailed him for having a .40-caliber pistol under his pillow—a case they pursued, in part, because he was undocumented. He got two years in prison and was put on track for deportation.

The feds have even gone after a cop for returning guns to a known drug user, even when that person is being friendly to law enforcement. In 2002, the DOJ charged an Iowa police officer for, among other things, giving firearms back to a drug user who’d begun to cooperate with the Drug Enforcement Agency.

When ATF goes after someone solely for being a drug user with a gun, it’s usually a pretty extreme circumstance. For example, the feds charged a Nebraska meth user in 2008 with a single count of a user-in-possession of a gun—but only after discovering his sizable collection of 18 rifles, 11 shotguns, a couple of pistols, and a revolver. Even then, he spent only a few months in jail after getting caught using drugs while out on bail and was eventually sentenced to time served.

The question now is whether Biden’s case marks a turn in how the feds pursue this type of charge—or whether avoiding prison time is the special treatment Republicans in Congress keep railing about.