Scott Shepherd was in Oslo, Norway, mid-performing his epic recitation of The Great Gatsby in the Elevator Repair Service’s production Gatz, and very aware of a woman sitting in the middle of the front row.

“She uncorked a bottle of wine, and she rolled a cigarette,” recalled Shepherd, and when a particularly melodramatic confrontation unfolded was extremely vocal about what she thought the characters could do.

Then there was the time in Singapore when the lighting failed during Jay Gatsby’s funeral scene. “Three to four minutes we were in complete darkness, all gathered around Gatsby’s coffin. Then the audience turned their cell phones on. We were all lit by this collection of blue lights.”

An eight-hour adaptation of The Great Gatsby, read word for word (and including breaks), may not sound like electrifying theater. But it most surely is in the hands of Shepherd and the ERS theatre company.

For Gatz’s return to New York City after its rave-received run in 2010 (when this author first saw it), old-time fans and curious first-timers are equally welcome. At NYU’s Skirball Center, they will see the handsome Shepherd play both an office worker slowly seduced by the book, and then the book’s narrator Nick Carraway, at all times seemingly reading from a copy of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel.

Shepherd isn’t. He has memorized every single word of the 1925 novel. The drama we see is The Great Gatsby, but it is also about the power of that a book exerts upon a reader.

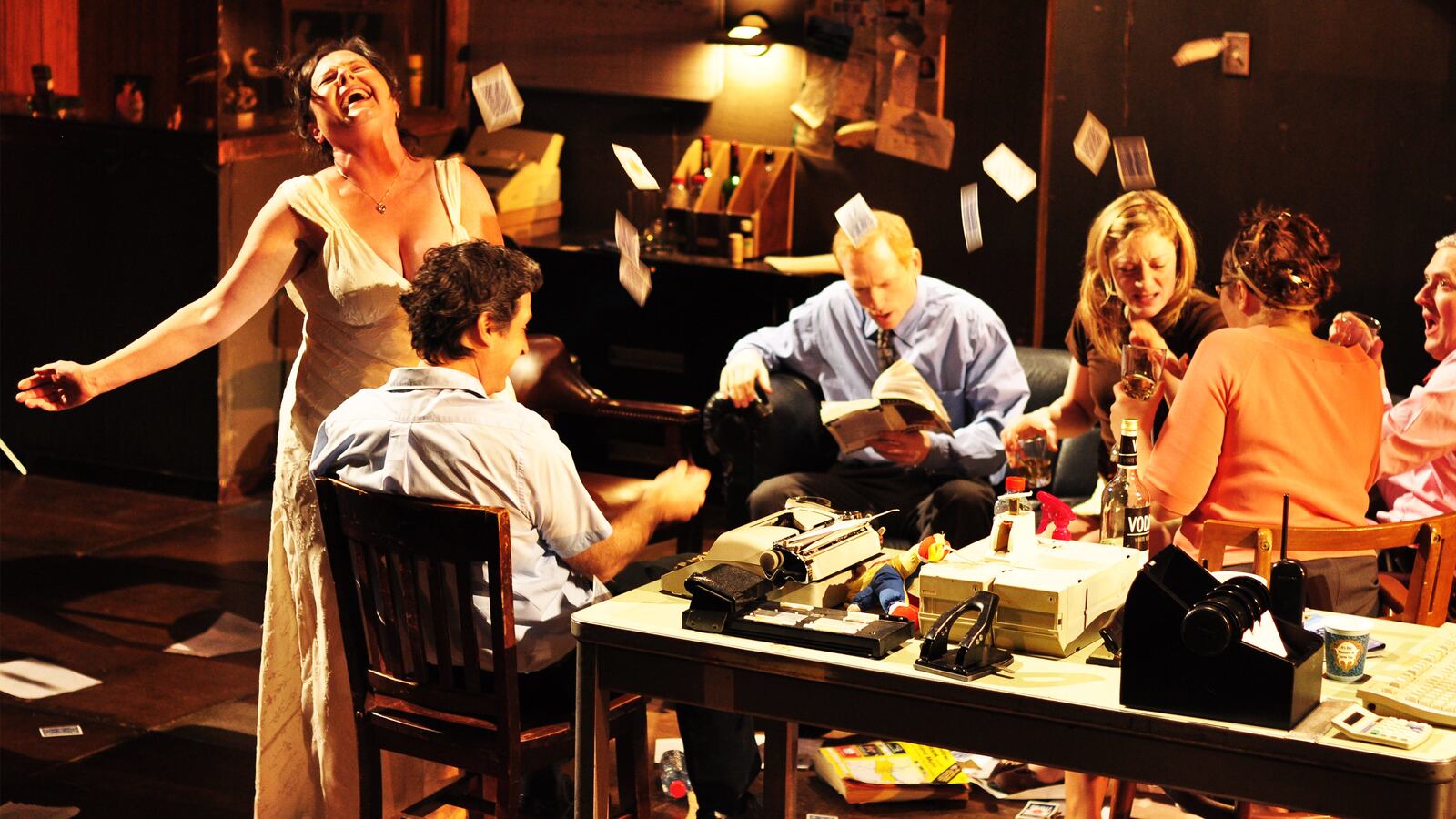

Around Shepherd a company of actors play out scenes from the book in what looks like a dusty office full of files, cabinets, bored workers, and dim pools of light. It is not the setting Fitzgerald sketched. The play starts slowly, before explosive confrontations and raucous party scenes.

John Collins, artistic director of the Elevator Repair Service, said the company had first performed Gatz in 2004, for a four-week run in a 75-seat theater. In the intervening years it has been performed in Los Angeles, London, NYC (again), and last September in Abu Dhabi.

Collins said he had felt “some dread” about that performance of the play, the first in a number of years. “My worry was that it wouldn’t feel fresh any more. How would the UAE audience respond to it? Would the thrill be gone for us? We would all feel too old…” He laughed.

Instead, he felt “emotional” and “moved” in seeing it done again, and how well it held up. He still had faith in it, despite the “exaggerated popularity” the show had in the past.

“It feels like a lot to live up to,” Collins said. He’s worried that those who saw it in 2010 (like this author) will come and see it in 2019, and not feel the same magic. “But this is a natural anxiety to have about something that got universal praise. It certainly had its detractors, not everybody loved it.” But Gatz was predominantly lionized, and so the pressure to get it right remains.

One adjustment is to play it on a bigger stage than its last New York engagement at the Public Theater, where a small stage gave Gatz an added intensity. The text and conception of the play won’t change. “The text is a pretty fixed element of the piece,” Collins laughed.

There are minor changes in action, where Collins and the company have spied over the years opportunities to illuminate the text that Shepherd is reading; conversely, there are moments when you are simply listening to Shepherd’s wonderful delivery.

“It is strange to bring it back for a couple of weeks—like a sort of encore,” said Shepherd of preparing to dust down Gatz again. After its run at the Skirball Center, Gatz tours to Princeton, NJ, and Perth, Australia.

“This was a ,show I thought was safely locked in the trunk, but it seems like it’s maybe having a second life now,” said Shepherd. “We’ll have to see.”

What should Gatz first-timers expect?

“There is a recitation of The Great Gatsby embedded in what we do, but that is not the totality of what we do,” said Collins. “In Scott as Nick, this is the story of someone becoming completely lost in a great novel. And it is a slowly emerging hallucination of the novel against a very unlikely backdrop. I think what people will see a play about the profound imaginative experience of reading.”

Things begin so slowly in Gatz, as Collins said, that you may be under the mistaken impression that all you’ll be watching is a guy sitting at a desk reading the novel, doing different voices for different characters. The early pages of the novel are reflective exposition, so stick with it. Soon, Shepherd as the office-bound Nick starts trying to do clerical duties as he reads, other characters wander in, and soon their actions organically align with what is happening in the book.

Scott Shepherd

Paula Court“Nobody walks on stage trying to convince you they are Jay Gatsby or Tom or Daisy or Dick,” Collins said. The office idea came from Collins and Shepherd and another actor meeting in a little office at the theatrical space where Gatz was first performed in the infancy of the project.

They were wrestling with where and how to set Gatz. They looked around and thought, for the sake of experimentation, to use the office itself, with Shepherd as a worker hiding from his boss to read the novel.

“It stuck as a concept because unlike lots of other adaptations of this novel you get at something more truthful by not having to buy into the period glamor and glitz,” said Collins. “Ultimately this novel isn’t about those things, but about people in the novel imagining those things. What makes it a profound story is that it is not about the great success of a reinvented man, it’s about the failure of it. It’s about the fact that Gatsby cannot accept who he was, and everyone else—Daisy, Tom—accept themselves either.”

Shepherd, speaking from Albuquerque where he is working on a film he declined to name (although he has grown a mustache and is wielding a 9mm Glock, he revealed), said he had some trepidation doing Gatz again in Abu Dhabi last year.

“But as soon as I dusted a layer of dust off the top of it, I was right back in this familiar place. If there’s been a gap of significant time, you’re blissfully free of the other problem which is kind of being locked into choices you’ve made, because it’s hard to get your mind out of patterns which have been working.”

Shepherd laughed when asked about memorizing the book.

“It was accidental. Fitzgerald’s text is like Shakespeare. The thing about memorizing Shakespeare is when you have it wrong you feel it, and when you know what the rights words are, you immediately know it: it sounds so much better. Shakespeare has a particular poetic meter and certain patterns of inversion. It just clicks. It’s just this pleasure, like a Dopamine hit or something. It’s similar with The Great Gatsby; a similar sense of poetry, and a similar pleasure for me in getting it right which makes it easier to memorize.”

Shepherd conceded he has a “freakish tendency to retain” information (except historical dates). He has read about the “memory palaces” that memory contest champions construct to save information; in Gatz that palace is very literally the office in which the play is set. The only chapter Collins asked him to memorize in full—no spoilers—is chapter 9.

Otherwise, although he appears to be reading from the book itself, he is not. He has it down. He switches between fake reading and real reading, he said. Her sometimes tests himself as he recites. One time, the book flew out of his hands, the section he had already read, falling loose on to the floor. Occasionally he uses the book as a crutch if he has a genuine memory lapse. “I call it a freak failure, because at events we do a thing called ‘Stump The Freak,’ the freak being me, and people attempt to stump me by reading out a few lines from the book from which I have to follow on.”

How does he do it for six and a half hours? Shepherd laughed. “I have a coffee before starting, a Power bar during the dinner break, and a cigarette halfway through the second half.”

Performing Gatz is exhausting, although Shepherd finds it “feeds” him too. On tour performing it, he was also working as a computer programmer and felt over-extended. Generally he finds it both “exhausting, energizing, and exhilarating, which is a bizarre combination. When the show is over I feel ready to hit the town. Then after the first beer I feel completely devastated.”

The original idea for Gatz came in 1999. Steve Bodow, Collins’ co-director at the time, had just re-read it, and felt the exuberance and new wealth of the time matched the Gatsby atmosphere. Collins read it for the first time. “It seemed the perfect novel to me, it was like a perfect crystal where everything was in exactly the right place.”

ERS asked the Fitzgerald estate for permission to stage it, “and we got the first of many no’s,” said Collins, with a laugh. They didn’t object to ERS’ office-set concept, but had committed themselves to another Gatsby-related theater project. The estate eventually relented, and, said Collins, like the first audiences was “startled by the humor in the show, particularly the screwball comedy. There’s such reverence for the book, people are often reluctant to accept the silliness of it and Fitzgerald’s own sense of humor.”

The writing takes care of the audience, said Collins, and that is true; but you don’t feel the hours passing. It is as immaculately and intimately directed as it is read by Shepherd. “It’s amazing to get to the final 10 minutes, and have absolute silence in the house,” said Collins. “People are sitting so rapt and drawn in. You have to come to Gatz, and let go. The play has its own orientation. You just have to come to listen. Scott Shepherd deserves tons of credit for that. He has such ease with the language and this language in particular.”

Collins knows that some people have left at the dinner break. He has noticed some reviews don’t mention details from the second half. For those who have said ERS is mocking The Great Gatsby in any way, Collins would recommend they read Fitzgerald’s text; it is, he said, all on the page.

“People have accused us of adding words, but Gatz is performed word for word as Fitzgerald wrote the novel. Gatz may surprise you if you know The Great Gatsby from the 1974 movie starring Robert Redford or Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 film, but you are going to hear what Fitzgerald wrote and see our characters experiencing that as well.”

There was some discussion of taking Gatz to Broadway when it became such a hit in 2010. “If that opportunity came along now I would certainly entertain it," said Collins. “It’s a special thing and would require some special faith from big investors.” Collins laughed. He added, if any reader had “a spare million dollars to spare,” then to get in touch.

Had Gatz been a burden as well as a proud theatrical herald for the ERS? Collins laughed, and said he had “complicated” feelings about it. They came to Gatz wanting to do something as original and unconventional as their other productions, which include an element of “generative failure” in attempting “an absurdly impossible task.”

Gatz had been surprising as it hadn’t failed in the way Collins and ERS had expected.

By reading The Great Gatsby word for word, they hoped it would be “audacious in a very appealing, intriguing way.”

It was, but the rave reviews also bought huge income and touring opportunities. ERS had produced a hit, and, as Collins said, with a success like that it means they had alighted on a magic formula. But risk defines the ERS. “Part of the reason I was reluctant to do it is because I hope we have other great things as artists to say and do,” said Collins.

He laughed recalling one lady, who approached him after another (but very different) verbatim production, Arguendo, about a Supreme Court case focusing on erotic dancing, “and said with a disappointed half-smile, ‘We liked Gatz.’ But an early belief of the company was that as soon as you have a successful formula, it deadens creativity. If you have a successful formula there isn't any danger in creating something new. You’ve eliminated all the necessary frustration of creating something.”

That said, Collins conceded, after Gatz came productions of William Faulkner’s The Sound and The Fury and Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, which, together with Gatz, came to be a kind of trilogy.

“We approached them differently. They weren’t verbatim. We couldn’t trot out another ‘You’re here for every single word of The Sun Also Rises, and it’s 17 hours this time.’ But they did contribute to the impression that we were a high-school novel staging company, which was lucrative and brought us both an audience and opportunities. It’s a difficult thing to step away from that, but we moved back into genuinely uncertain territory.”

Shepherd was concerned, like Collins, about the element of “turning out this horse again, doing the greatest hits aspect” when it came to performing Gatz in 2019, but the difference of six years—he discovered in Abu Dhabi—was in how he had grown and evolved as a performer, and tweaking what did and didn’t work any more: "I haven’t changed anything fundamentally about the essence of the character, but I do feel there is something about being six years older and coming at it from a different point of view.”

Shepherd said, “Some days when I’m standing beside the door waiting to go on, I think, ‘Boy, do I have to do this whole thing again.’ But there’s nothing like the end of Gatz in rest of my performance career. At that point you’ve been with the audience all day. The audience themselves are experiencing that elation of being there all day. They’re proud of themselves for going that far, you can feel them experiencing this close accumulation of concentration of 8 hours on one thing.

“The book does not let you down in terms of Fitzgerald’s own performance, which has been so good since chapter 1. Then he outdoes himself in the final paragraphs. When I come to the end of Gatz it’s always extraordinary.”

The next ERS production, Collins said, will return the company to its roots in that it blurs the lines between audience and actors. Collins says ERS may adapt other novels; transforming a novel into a play, one genre into another, comes with “problems to solve” which is central to the ethos of ERS. “We don’t like things where the problems are already solved,” Collins said.

And, who knows, that next bout of “generative failure” may produce another theatrical hit.