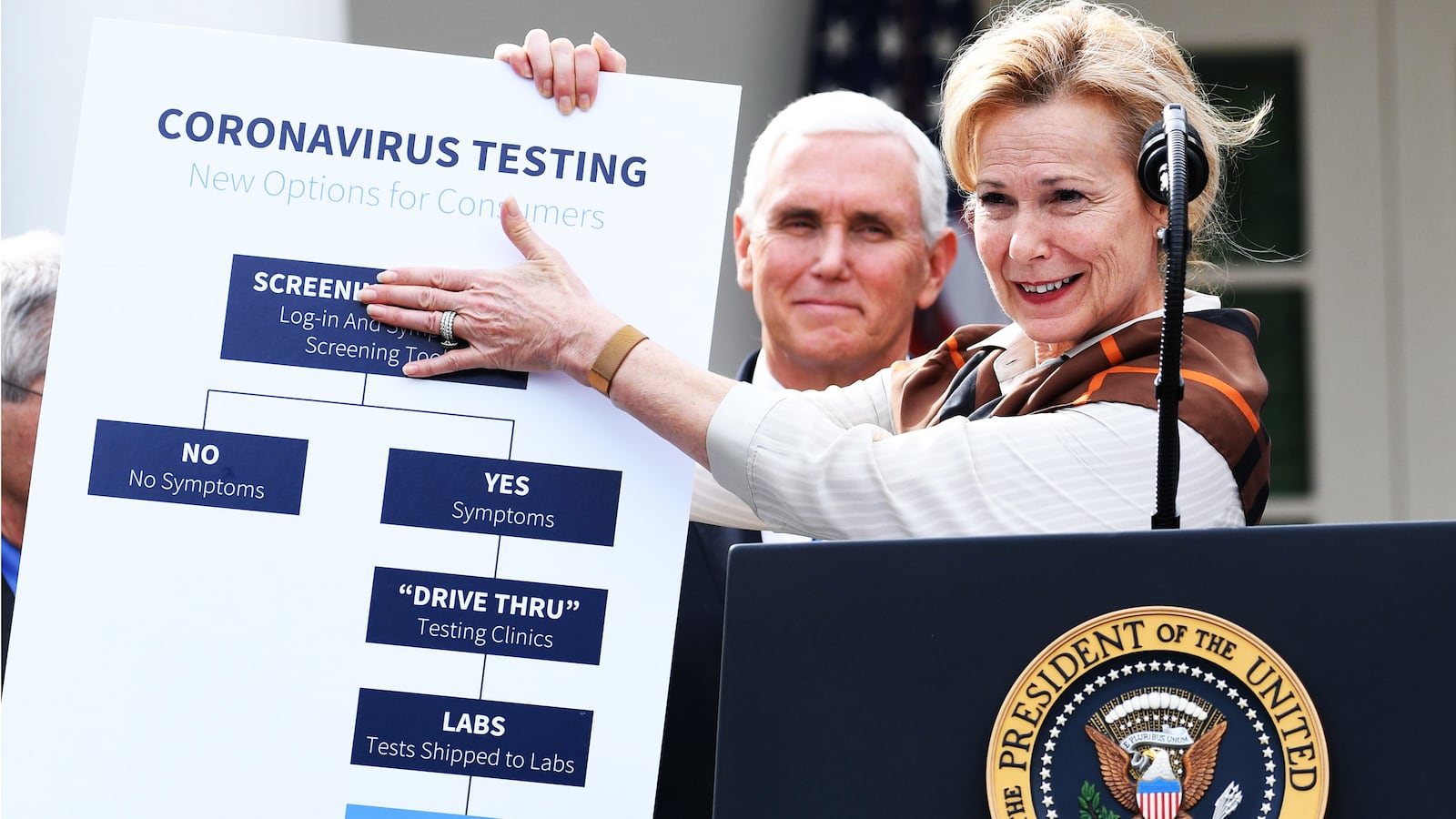

Perhaps it was clumsy language and an even clumsier tone, but speaking clumsily and looking giddy when invoking the 1980s, when so many gay men died of AIDS—in the midst of massive governmental homophobia—is jarring, particularly for a health official who lived and knows that history. On Friday, President Trump’s White House coronavirus press conference featured the highly respected Dr. Deborah L. Birx—the State Department’s U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator—sounding just like that.

It was plain weird for Dr. Birx, whom Mike Pence appointed as the White House’s coronavirus response coordinator, to breezily invoke the 1980s as such an illuminating time when the government learned so much, which now informs their response to the coronavirus. It sounded too dandy.

The truth of that history is not so dandy. LGBTQ people and their allies of that time remember something much starker: the Reagan administration’s sheer callousness, ignorance, and a willingness to let people die horrible deaths while judging and demonizing them. For the first years there appeared to be little desire to learn anything; quite the opposite.

Dr. Birx said: “In less than two weeks together, we have developed a solution that we believe will meet the future testing needs of Americans. I understand how difficult this has been. I was part of the HIV/AIDS response in the ‘80s. We knew from first finding cases in 1981. It took us to almost 1985 to have a test. Another 11 years to have effective therapy. It’s because of the lessons learned from that we were able to mobilize and bring those individuals that were key to the HIV response to this response.”

Any learning that was done over 30 years ago was done because LGBTQ activists and their allies were doing the teaching, and doing that teaching through a mixture of anger (directed at politicians, officials, scientists, and the medical community), rapid accrual and dissemination of knowledge to their communities, and compassion and bravery (as they tried to take care of their loved ones who were dying, sometimes with sterling medical support and too often with not).

If anything, anyone from that era may look at the White House coronavirus press conference on Friday and think, “Well, at least the government seems to care this time. You sure as hell didn't in the 1980s. There were no Rose Garden press conferences about strategies to tackle AIDS back then.”

Dr. Birx’s too-brisk crunching of 1980s history does not match the real, much gnarlier and far more painful timeline. She, like Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, knows that era all too well; she, like Fauci, has 30-plus years of experience in the HIV and AIDS field, a time “when you not only couldn’t make a diagnosis, you didn’t know what the problem was, and you didn’t know how to treat it, it was devastating,” as Dr. Birx told the George W. Bush Presidential Center in 2019.

If the present team of coronavirus experts are crediting their 1980s experiences as instructive, then they should also do some proper name-checking—starting with Larry Kramer, Peter Staley, Sean Strub, ACT UP, and Gay Men’s Health Crisis.

This was an era, from 1981 onwards, when people with AIDS died horribly. It was also a time that, as the pandemic grew, the American government did worse than nothing. They twinned with the religious right to make LGBTQ people, and people with AIDS’ lives appalling. Reagan and his administration let people with AIDS die terrible deaths. Reagan only mentioned the word “AIDS” in public for the first time in 1985—and this was no set-piece speech to show engagement with the issue, but simply in response to a reporter’s question.

Watch Kramer’s The Normal Heart, or Tony Kushner’s Angels in America; bodies of AIDS patients were being just dumped. No one wanted to touch them. Families rejected children as they lay dying. Read Randy Shilts’ And The Band Played On, Edmund White, David B. Feinberg, Sarah Schulman, Andrew Holleran, David Wojnarowicz, Paul Monette, and David France’s How to Survive a Plague (and the documentary). Watch TV shows like Pose and films like Longtime Companion; gay men and their allies had to find their own way through this. The government, media, and church looked on, not impassively, but with venom and prejudice.

Any person who is a survivor of that era, or who lost a loved one, or who remembers that time, may have been watching the last few days and allowed themselves a disbelieving smile as governments, experts, and journalists rushed and dithered over what to do and how quickly to do it. In the 1980s, during the HIV and AIDS pandemic, there was no sense of that urgency, at least publicly.

Dr. Birx and Dr. Fauci may have been working hard with scientific colleagues to find solutions (and they are rightly recognized as leaders now), but their work was not as emphatically supported by the government then as their efforts to stem coronavirus is now. They were also eyed with suspicion by activists, who saw scientists as working too closely with drug companies to the detriment of AIDS patients.

“When the activists started to appropriately react to the rigidity of the clinical trials [to research anti-HIV drugs], for instance, they started storming the NIH and burning people like me in effigies, and Larry Kramer, now a close friend, was calling me a murderer,” Fauci has said. “The best thing I’ve done from a sociological and community standpoint was to embrace the activists. Instead of rejecting them, I listened to them.”

Fauci’s point is well-made. As coronavirus evolves and develops, it is vital to listen to those—patients, doctors, and nurses—living at its sharpest end to inform the most effective policy responses.

Dr. Birx was not incorrect in what she said on Friday. But her tone was wrong, and she was missing a few vital sentences. The AIDS pandemic spiraled out of control because a government did not care for those that the pandemic most sharply affected. It did not listen to them, or care for them. Instead, it stigmatized them.

In response, the LGBTQ community, while enduring the general prejudice and hatred of that time, showed up for each other and schooled the wider world—including scientists like her and Dr. Fauci—in how to respond to a pandemic. It was a selfless, socially magnanimous, and sadly utterly necessary response. The first commemorative looped ribbon, before we began drowning in them, was the red AIDS ribbon.

If that era provides any kind of model, it is squarely down to LGBTQ activists like Kramer, Staley, Strub, ACT UP, and GMHC—and the peer-based mobilization they oversaw within the LGBTQ community and pressure they brought to bear on governments, organizations like the CDC, and the world of science.

Acquaint yourself with their ingenuity, passion, bravery, their never-taking-no-for-an-answer, and their witty and sexy confrontations. Eventually, they prevailed, but it was a brutal fight. Sure, learn from it when it comes to coronavirus—but also credit them for it, and remember that dark period of history for what it really was.