At the start of Donald Trump’s second impeachment trial, Democrats thought they knew how it would end: with Trump’s acquittal and the party unified behind the case that was made against him.

Ultimately, that was the ending Democrats got on Saturday—but not without a few surprising twists.

In the inevitable march to a second Trump acquittal, a surprising seven Republican senators joined Democrats in concluding the ex-president was guilty of inciting the insurrection at the Capitol on Jan. 6. Where in January 2020, Sen. Mitt Romney (R-UT) was the only Republican to vote for Trump’s conviction on the charge of abuse of power; this time, he was joined by Sens. Susan Collins (R-ME), Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), Bill Cassidy (R-LA), Pat Toomey (R-PA), Ben Sasse (R-NE), and Richard Burr (R-NC).

ADVERTISEMENT

The remaining 43 Senate Republicans voted to acquit Trump, many citing the highly disputed claim that it’s unconstitutional to convict a former president—even if some of them blamed Trump for inciting the deadly riot. Trump, said impeachment manager Rep. Joaquin Castro (D-TX) after the vote, “was let off on a technicality.”

But the route to that historic vote was a bumpy and chaotic one, and it angered seemingly everyone in the Democratic Party, opening up rifts about their core values and priorities in the post-Trump era, and undermining the unity they’d shown up to that point.

It began when Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-MD), the lead Democrat prosecuting the case against Trump, appeared on the Senate floor Saturday morning to deliver what everyone thought would be his closing argument. Instead, he dropped a bomb: he motioned for additional testimony to be heard in the trial.

Democratic senators—who said they would defer to Raskin’s team on calling witnesses but made it clear they wanted to get the trial over with—had no idea the announcement was coming. Several of the aides working closely with the nine impeachment managers had no idea, either.

At issue was a piece of evidence that drew scrutiny late in the trial. A CNN article published Friday night reported that Trump called House Republican leader Kevin McCarthy (CA) on Jan. 6 and, among other things, told him that the mob storming the Capitol was “more upset” about the election than McCarthy. Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler (R-WA) had publicly confirmed this detail a month ago, and Democrats wanted to call her in for a deposition to explain the damning episode and provide more information.

A bipartisan majority in the Senate voted to allow more testimony after Raskin requested it. But a frantic three hours later, Democrats caved, simply saying they would accept Beutler’s statement on the Trump-McCarthy call being read into the record as opposed to being provided through a sworn deposition or testimony. The trial then proceeded to closing arguments, as if the puzzling detour didn’t happen.

As commenters around the political spectrum scorched Democrats for the reversal, furious aides on both sides of the Capitol questioned how it could have happened like this, with Democrats backing down after securing 55 votes for witnesses, including five Republicans, who could shed more light on Trump’s conduct on Jan. 6. Many strongly supported having as much information as possible for the historic record, even if Trump’s acquittal was a foregone conclusion.

When it became clear that the Democrats would back down, the self-deprecating gallows humor began. Several aides texted The Daily Beast a famous joke from The Simpsons, a scene showing a fictional party convention with a slogan on banners: “We hate life and ourselves!” and “We can’t govern!”

There was ample blame to pass around internally. Some pointed the finger at Senate Democrats, who were perceived by some in the party as eager to dispense with the trial—an exercise they were tepid on to begin with—so they can move on to coronavirus relief and Biden’s agenda. A report from CNN on Saturday afternoon indicated that Senate Democratic leadership “pressured” the managers to fold on moving ahead with witnesses.

The fact that no legislative business is scheduled for next week, theoretically giving more space for expanded trial proceedings, rankled many.

“If you’re a Senate Dem and next week is already wide open, why not just roll with it? What do you lose by taking testimony?” asked one source familiar with the impeachment strategy. “It’s vintage Washington, DC Democrats. We box Republicans into a corner and then step back to let them off the ropes.”

But other Democrats said it was the impeachment managers who set the stage for the about-face. A Democrat familiar said that the managers were arguing until 3 a.m. Saturday about what to do, and did not notify Senate Democrats until five minutes before the trial’s 10 a.m. start time that they intended to call witnesses. “After the vote, it was clear the managers had no plan,” said the source, who added that the managers then decided to reach an agreement with Trump’s team on entering Beutler’s remark into the record. A spokesperson for the managers’ team did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

At a press conference following the vote, the Democratic managers defended the decision not to call more witnesses, arguing that most Republicans would have acquitted no matter what. Raskin said the decision to push for the initial vote was his call and said he’d accept any blame.

Before the Senate convened Saturday morning, Democrats’ prosecution of Trump was on track to fail in delivering a conviction but succeed in ratcheting up the political pressure on those who still defended the ex-president.

Knowing that getting 17 GOP votes to secure Trump’s conviction was a longshot, the House managers had put together a brisk but powerful case that Trump incited the Jan. 6 riot. Even Trump’s biggest supporters in the chamber admitted that Democrats had handled it capably, lavishing praise on Raskin’s team for putting together a compelling argument, a bar that many Republicans noted that Trump’s own defense lawyers did not clear.

The responses from the GOP senators who voted to convict—a mix of Trump critics, retiring members, and wildcards—referenced the effectiveness of that case.

Saying that Trump is guilty of inciting an insurrection, Burr said that “by what he did and by what he did not do, President Trump violated his oath of office to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

In a statement, Romney agreed with virtually every charge the Democratic managers made. “President Trump incited the insurrection against Congress by using the power of his office to summon his supporters to Washington on January 6th and urging them to march on the Capitol during the counting of electoral votes,” said Romney. “He did this despite the obvious and well known threats of violence that day.”

Even top Republicans said they were quite close to considering the ultimate punishment for the ex-president. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), who was reportedly open to conviction, wrote in an email to colleagues on Saturday morning, that his decision to acquit was “a close call” but said “I am persuaded that impeachments are a tool primarily of removal and we therefore lack jurisdiction.”

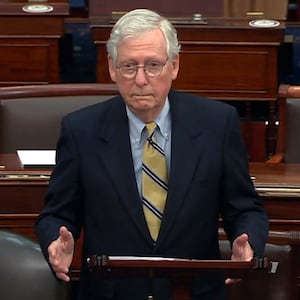

In a speech from the Senate floor after the vote, McConnell was even harsher, even though he voted to let Trump off the hook. "There's no question—none—that President Trump is practically and morally responsible for provoking the events of the day,” he said. “No question about it.”

The GOP leader even suggested Trump could still face accountability and pointedly noted that civil and criminal proceedings are possible. But he said he voted to acquit because the Senate was not the proper venue for trying an ex-president—though McConnell could have facilitated an earlier trial if he had wanted to. “We put our constitutional duty first,” he said.

The Democrats prosecuting the case were determined not to let that argument—one adopted by most Republicans who voted to acquit—slide. After the witness drama had passed, they used their closing arguments to reinforce the stakes of the question at hand: laying down the marker that Trump’s actions on Jan. 6 warranted the strongest possible response.

“Senators, this trial, in the final analysis, is not about Donald Trump,” said Raskin in his closing argument. “The country and world know who Donald Trump is. This trial is about who we are.”

“This is almost certainly how you will be remembered by history,” he continued. “That might not be fair, it really might not be fair, but none of us can escape the demands of history and destiny right now.”