During the first presidential debate, NBC’s Lester Holt asked Hillary Clinton, “Do you believe that police are implicitly biased against black people?”

Hillary Clinton answered, “Implicit bias is a problem for everyone, not just police. I think, unfortunately, too many of us in our great country jump to conclusions about each other. And therefore, I think we need all of us to be asking hard questions about, you know, ‘Why am I feeling this way?’” Clinton also said, “We’ve got to address systemic racism in our criminal justice system.”

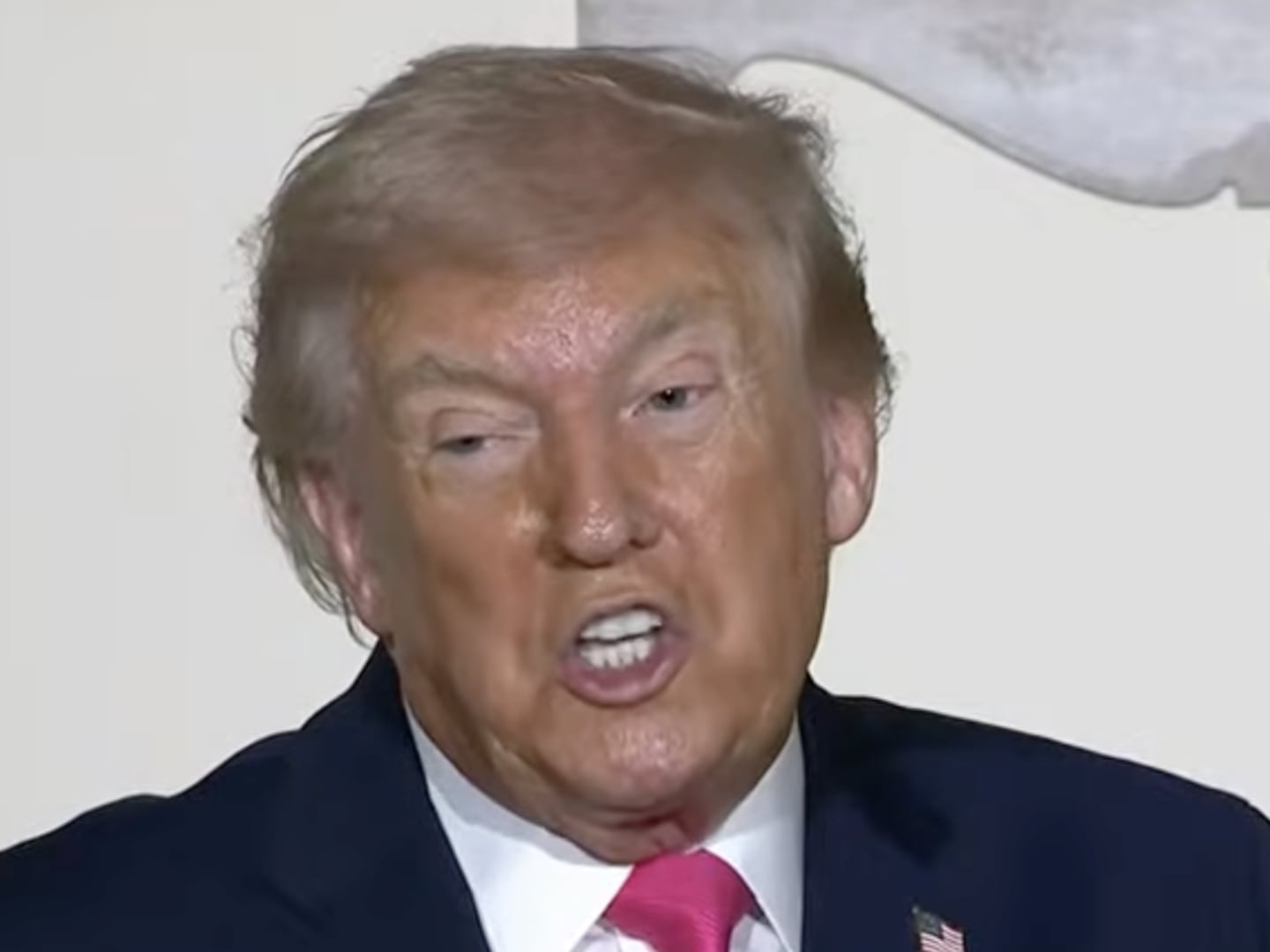

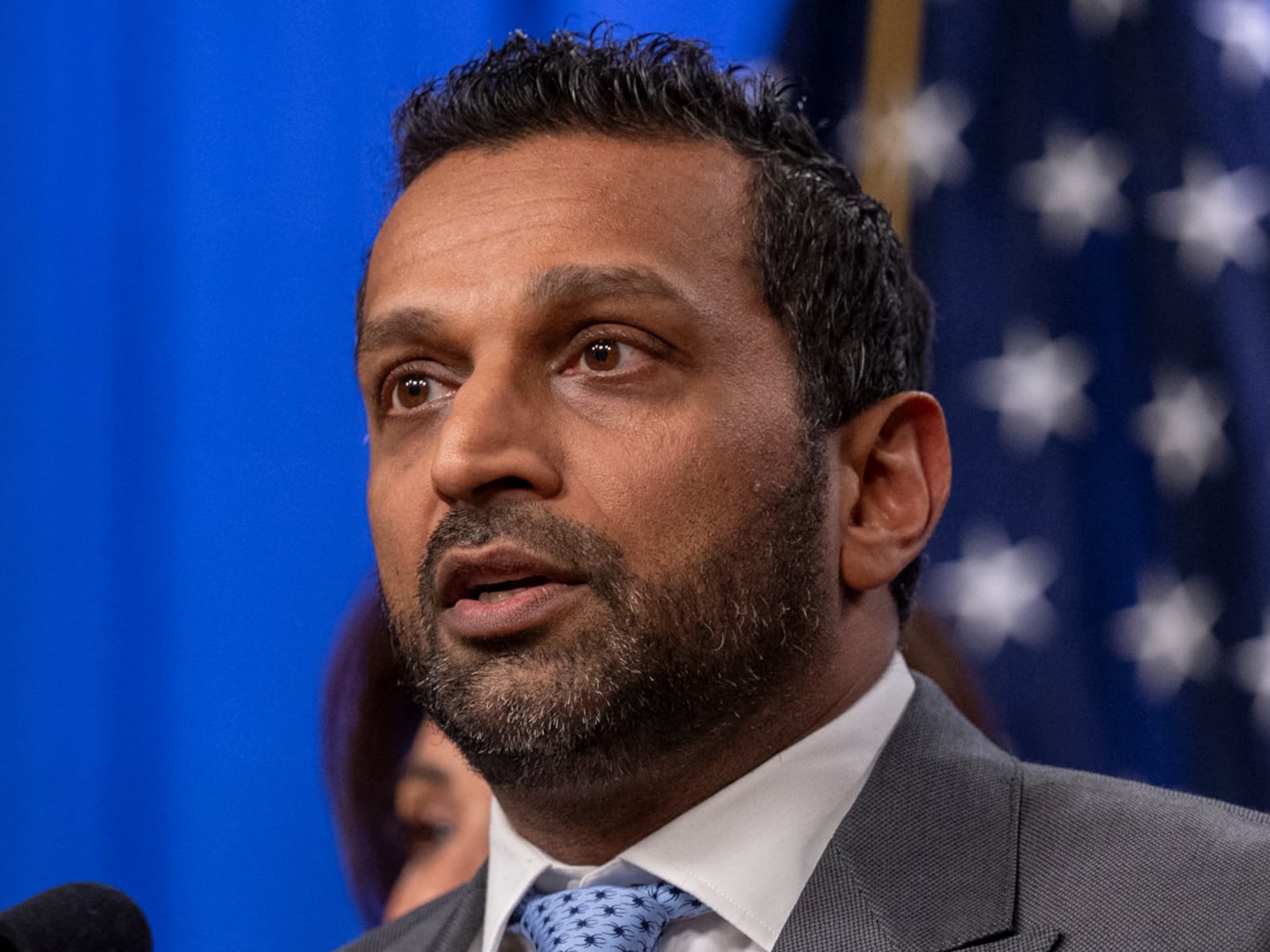

The right wing exploded. Days later, Donald Trump said that Clinton was “suggesting that everyone, including our police, are basically racist and prejudiced.” Then vice presidential candidate Mike Pence, in his own debate comments, laid into Clinton. “Enough of this seeking every opportunity to demean law enforcement broadly by making the accusation of implicit bias whenever tragedy happens,” Pence fumed. Pence went on to note that some of the shootings of unarmed blacks were by black officers. His implication was that disproportionate police violence against the black community can’t be due to implicit racial bias, because black cops do it, too. But Pence is wrong on this. Everyone is biased.

“There’s way too much research on implicit bias to deny its existence,” conservative columnist William Saletan wrote in response to Pence. “‘Implicit bias’ isn’t an accusation. It doesn’t mean you’re bad. It means you’re normal.” And because implicit bias is normal, normal people have it. That means black people, too.

This is one of the things that white college students have in common with black police officers—they’re all biased. Why? “Blacks and whites receive the same narratives and images that perpetuate stereotypes of black criminality and flippancy while synonymizing white culture with American values,” writes Theodore R. Johnson, a former navy commander who is a fellow at the New America think tank. In an article in the Atlantic, Johnson writes about discovering his own implicit antiblack bias as a black man after taking the Implicit Association Test (IAT), the test most commonly used to measure implicit bias. Johnson writes, “My own hidden biases punched me in the gut.”

I thought back to a trip I’d taken with my friend Scottie Nell Hughes, a colleague at CNN and prominent Trump supporter. In October 2016, Scottie and I find ourselves together in Farmville, Virginia. Vice presidential candidates Mike Pence and Tim Kaine are at Longwood University for their one and only debate during the election campaign, and Scottie Nell and I are both there for CNN’s coverage. Long before this debate, Farmville played a far more important role in U.S. history. In 1951, black students at Robert Russa Moton High School staged a walkout to protest the intolerable conditions of their segregated school, and to challenge segregated education in general, a vestige of Jim Crow laws that persisted in Virginia and nationwide. Ultimately, the Moton High walkout helped lead to Brown v. Board of Education. When the Supreme Court struck down school segregation in 1954, three-fourths of the plaintiffs in the case on which they ruled came from the Moton school. But it wasn’t until 1959—and only under federal pressure—that Virginia finally started the process of integration.

Prince Edward County—where Farmville is located—didn’t want to integrate its public schools, so the country just shut them all down instead. For five years, Prince Edward County had no public schools. White kids flocked to all-white private schools that were being created in response to integration. The county’s black students crammed into churches and living rooms as volunteers from the community and some teachers from up north tried to give the students the education they were missing. It took another Supreme Court case to force the county to reopen its schools in 1964.

The school is now a museum, and Scottie Nell and I have a little downtime. Side by side, we walk through the halls of the former Robert Russa Moton High School without speaking. Each room captures a snippet of history, with photographs and text that explains what happened then, but the history you can’t see in each room, what that space represents, is palpably heavy. We’re both trying to read as much of the wall texts as we can, taking it all in.

After a long while of moving from room to room in silent contemplation, I finally speak.

“This is just so awful,” I blurt out. I don’t know what else to say, but I want to say something.

“Yeah, it really is,” Scottie Nell replies. And then we both take a deep breath at the same time, followed by more silence. Because really, what more is there to say?

Then, maybe a minute later, Scottie Nell adds, “But thankfully it wasn’t everyone who supported this.”

“Huh?” I respond. “What do you mean?”

“Well, I mean, thankfully most of the white people thought this was wrong,” Scottie Nell says. “It was just some bad apples who supported it.”

“No, Scottie Nell, it wasn’t,” I say, trying to sound earnest but probably sounding as shocked as I feel. “It was most of the white people. The vast, vast majority of the white people supported and defended segregation.” A 1942 poll confirms this. It asked Americans whether “white students and Negro students should go to the same schools.” Only 30 percent of Americans—nationwide—said yes. In 1956, the same question was asked, and support for integration still fell below 50 percent. And that’s just the people who were willing to admit it to the pollster.

I turn and face Scottie Nell. “I like to think that if I’d been alive back then, I would have fought against segregation,” I say. “But the odds are, I wouldn’t have. That’s just a reflection of the reality of the time that I would have been a product of, just as much as anyone else.”

“You don’t know that!” she says, raising her voice and becoming more and more visibly upset. “You don’t know what your ancestors thought or what they believed.”

Clearly, Scottie Nell has never met my racist grandfather, but that’s not the point. The point is statistics. “I know that the vast majority of white people back then supported segregation, and the odds are that I would have been one of them,” I say.

Not because I’m an evil person but because that’s how hate works—when it’s all around us, we soak it in and regurgitate it. In the case of the U.S. in the ’50s, we’re talking about explicit aggressive racism, but the same is true of unconscious bias.

“I wish that wasn’t true,” I say to Scottie Nell, “but it is.”

Let me be clear. I believe that most Americans today really don’t consciously subscribe to racism or most other overtly bigoted beliefs. Even still, African Americans are incarcerated at five times the rate of whites and receive harsher sentences for the same crimes. Women earn less than what men earn for the same work. LGBT youth are disproportionately more likely to be homeless. Unemployment rates for black and Latino Americans are almost double those for whites. If we’re no longer, by and large, overtly bigoted, how do these blatant injustices persist?

A large body of research assigns some of the blame to our unconscious biases—or, as the academic community calls them, “implicit biases”—the attitudes and misperceptions that are baked into our minds due to systemic racism and pervasive stereotyping across society. As products of a sexist society, we all have a bias in favor of men and masculinity and against women and femininity. As products of a racist society, we all have a bias for white people and against people of color. As products of a classist society, we all have a bias for rich people and against poor people. And so on. We don’t consciously hold these beliefs; they’re like deep-down reflexes we’ve habituated to over time. They’re encoded in our brains and, in turn, they play out in ways that then reinforce society-wide bias.

For the record, I don’t think Scottie Nell Hughes is a deliberate, explicit bigot. And I don’t think the vast majority of Americans—right, left, and center—are deliberate, explicit bigots. But I do think all of us need come to terms with the fact that we all hold unconscious ideas about the superiority of some groups and the inferiority of others—ideas that may not be expressed like they were in ’50s Virginia but that come from that same history and hateful legacy. And when I say all of us, I really do mean everyone. Myself included. And you, too.

Adapted from The Opposite of Hate: A Field Guide to Repairing Our Humanity by Sally Kohn © 2018 by Sally Kohn. Reprinted by permission of Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. All rights reserved.