Man’s best friend wasn’t left out of the afterlife journey in ancient Egypt.

Underneath Egypt’s earliest pyramid, archaeologists have found remnants of an estimated 8 million mummified animals.

According to a new research study, a 5,000 square foot network of underground tunnels are stuffed full of linen-wrapped dogs, along with a few foxes and cats laid to rest thousands of years ago by the cult following of a canine-like deity who Egyptians believed would usher them into the afterlife.

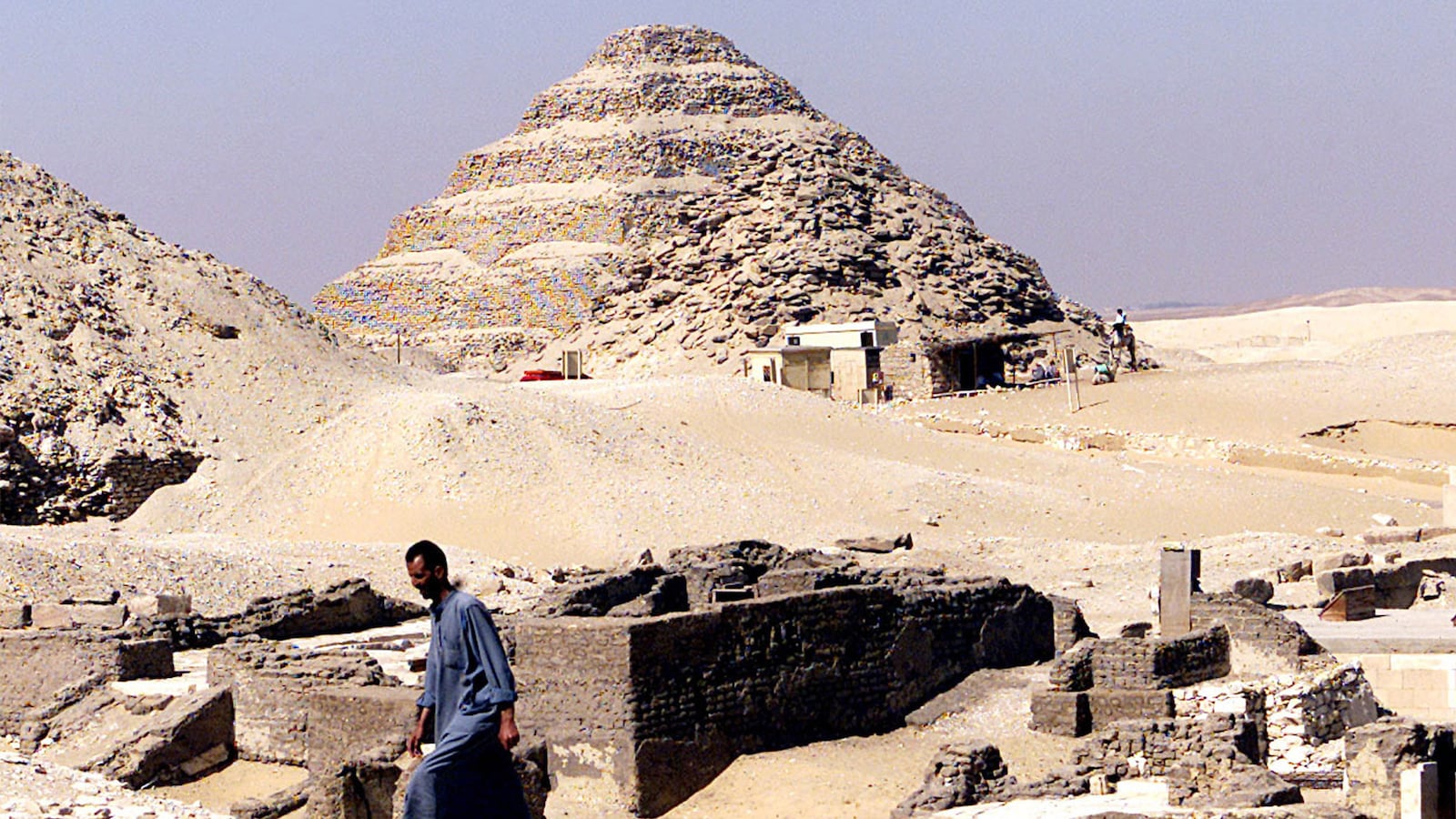

About an hour from Cairo, the Saqqara temple complex is the final resting place of royals, commoners and an enormous quantity of sacred beasts.

In the June study published in the Cambridge University-based journal Antiquity, Cardiff University and Egypt Exploration Society researchers outlined their findings from decades studying the area and six years mapping the monument.

It’s the first time modern techniques have been used on the site—the last map was sketched in 1897 by a French archaeologist.

The Catacombs of Anubis are located near the Step Pyramid on the Saqqara plateau, one of the most famous destinations for pyramid visitors.

The necropolis is filled with human burial sites, but underneath is where researchers found the real treasure laid.

“The temples and shrines, though undeniably significant, are often only the tip of the iceberg,” the study’s authors wrote.

Beneath the oldest pyramid was a labyrinth of stone tunnels and at least 49 galleries filled with an astounding number of mummified animals.

Anubis, a deity with a canine head, was the god of embalming. It was he who ushered the dead from the living world to the underworld.

In ancient Egypt, animals resembling gods were considered to be their modern-day incarnations and so 90 percent of the animals offered as sacrifice to Anubis were canines: dogs, jackals, or foxes.

The wall slots of the tunnels were filled with fully-grown dogs who were given by donors of higher status, but in the general stacks of remains, researchers found most of the bones belonged to puppies who’d been killed almost immediately after birth.

The quantity of newborns was so high that the authors posit there were ancient puppy mills “probably in Memphis and its environs, from which most of the animals were sourced.”

The catacombs have not been officially dated, but burial sites there stretch at least as far back as 3100 BC and perhaps 2,000 years earlier, according to a 2013 study in the Archaeological Review from Cambridge.

The area was home to the very first pyramid and enjoyed huge quantities of visitors as one of the holiest pilgrimage destinations.

These travelers would come with or purchase a gift to appease the gods, in this case, an animal. They believed the creature would then pass along its donor’s wishes to the deity.

Animal sacrifice was rampant in ancient Egypt. Across the country, an estimated 70 million mummified animals have been located by researchers.

Studies of these catacombs have unearthed birds, cats, and even a crocodile mummified and offered to the gods. Some have stayed specific to the creature, like the canine tombs in Saqqara, and another catacomb holding two million ibis birds.

This system, along with the sheer scale of mummies found, has led researchers to believe that there was a large-scale animal breeding system in place, possibly something akin to a puppy farm.

Part of the research into the site involves a molecular biologist who has been collecting these bones and will analyze their DNA to see if how they were bred.

There may have even been a market for fake animal mummies, as studies have found some of the pieces contain little to no animal remains.

“The ancient Egyptians weren’t obsessed with death — they were obsessed with life,” Smithsonian curator Melinda Zeder told the BBC. “And everything they did to prepare for mummification was really looking at life after death, and a way of perpetuating oneself forever.”