At the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, the location where tradition says Jesus was born, something strange was recently discovered hidden inside the church’s octagonal baptismal font. In the course of restorations and renovations to the building, a much older baptismal font was uncovered. The newly discovered Byzantine baptismal font dates to the sixth century, a mere 200 years after the Church of the Nativity was built. But for most of its 1500-year history it has lain hidden from the world.

Ziad al-Bandak, the head of the Palestinian presidential committee that leads and oversees the church renovation, said last week that the font was a “magnificent” discovery and that the stone used in its construction appeared to match that of the church’s columns. “Nobody knows,” al-Bandak said, “why it has been covered and put in this place and never written in any historical book about it, either in the church or in the historical books.”

The church itself has something of a tumultuous history having been deeply affected by the shifting religious and political power structures in the region. The original Church of the Nativity was commissioned by the Emperor Constantine the Great and his mother, Helena, two years after Helena undertook a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 325 A.D. Constantine wanted to construct a church that would honor the birth of Jesus in much the same way as he wanted to celebrate the death and resurrection of Jesus by building the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. Clearly, for Constantine, this was supposed to be one of the most holy places in the world. To this day, millions of visitors have visited the fourth century grotto underneath the church, the place that tradition maintains Jesus was born.

When archaeologists excavated the church in the 1930s they discovered a thick layer of ash, burned wood and broken tiles above the mosaics on the floor of the original church. This evidence suggests that at some point in the sixth century (some historians guess that it was 529 A.D.) the church was badly damaged by a fire. Shortly thereafter the Emperor Justinian rebuilt and expanded the structure. Unlike so many other ancient churches, the Church of the Nativity preserves much of that Justinian structure even today.

The current excavations at the Church of the Nativity began five years ago. In 2013 UNESCO declared the church a World Heritage site. City officials hope that the renovations—which have restored beautiful mosaics and columns—will boost tourism to the region. In 2018, Bethlehem Mayor Anton Salman said “Christians are leaving the Holy Land due to lack of peace and economic hardships and we are struggling to keep them in their homeland.”

The Church of the Nativity has not been immune to these hardships. In 2002, the church became the site of a siege when 200 Palestinian militants sought refuge there from Israel Defense Forces that had entered the West Bank. After 39 days the siege ended when many of those inside agreed to be exiled to Europe and the Gaza Strip.

Today, the restored mosaics and columns bring life and color back into a structure that, only five years ago, was greatly at risk and leaking water through its roof.

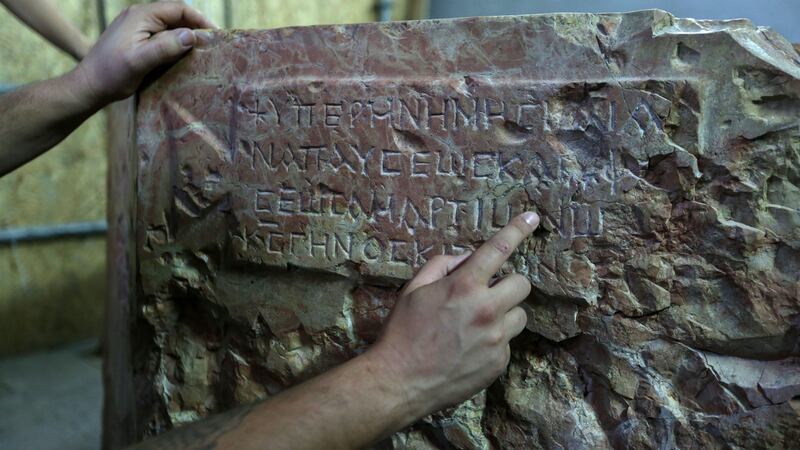

An ancient text on a baptismal font discovered at the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, West Bank.

Anadolu Agency/GettyIt’s easy to see why ancient Christians would have been interested in being baptized in Bethlehem. Baptism is a ritual of rebirth by which people die to their old lives and are reborn as Christians. What location (other than the River Jordan where Jesus himself was baptized) could be more appropriate for the baptism of oneself or one’s family members? Remarkably, the tradition associating this location with the birth of Jesus is much earlier than the fourth century. In the early third century Christian writer and philosopher Origen wrote that people in Bethlehem knew the cave in which Jesus was born and would identify it to others. (This doesn’t mean that Jesus was born in a stable-cave in Bethlehem, just that the tradition of his birthplace is an ancient one).

As to the previously hidden font, it seems likely that the newly discovered Byzantine font was incorporated into a later, larger design. Those renovating and adding to the church wanted to update the style of the design without destroying or neglecting the more ancient construction. The same phenomenon can be found all over Europe, where baroque facades conceal medieval Gothic architecture. The preservation of the Byzantine basin within the later octagonal font demonstrates just how important the history of the Church of the Nativity was to later generations of Christians. It’s the connection both with tradition and the physical space associated with Jesus’ life that give the place its significance. The fact that the font was retained and encased in another structure perfectly symbolizes how central contact with the Christian past is to the Christian present.