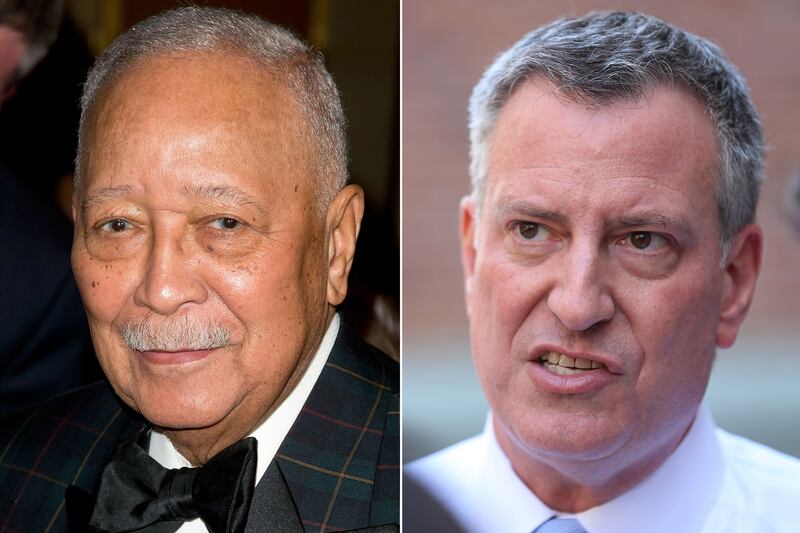

Bill de Blasio’s full-throated call for a left turn in New York City politics has vaulted him into the lead among the Democratic candidates for mayor. The public advocate is running a narrowly tailored campaign designed to fit the sensibilities of hard-core Democratic primary voters who chafed under the policies of Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg over the past 20 years. He promises the same combination of higher taxes on the wealthy and more government that characterized Giuliani’s precursor, liberal Democrat David Dinkins.

By contrast, de Blasio’s chief rivals, former city comptroller Bill Thompson and City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, are running what amounts to general election campaigns designed to appeal to a broad constituency, including those who think Bloomberg has done a decent job over the past 12 years, to win the September 10 primary.

For the broad public, the Dinkins years are best summarized by the opening lines of The Power of the Mayor: David Dinkins 1990-1993, written by the moderate Democrat Chris McNickle. “David Dinkins,” wrote McNickle, “failed as mayor … When David Dinkins governed, many New Yorkers felt adrift.” They “lacked confidence” in his ability “to run the city.”

Those looking to explain away Dinkins’s failings as New York suffered from record high levels of crime and taxes, a shrinking job base, and a dangerously swollen debt, insisted that New York, with its competing ethnic identities and intransigent interest groups, was simply ungovernable.

A key element in de Blasio’s appeal to liberal activists and older African-Americans has been attempting to revive the reputation of Dinkins, New York’s first black mayor. The Dinkins mayoralty meant a great deal to de Blasio, who met his wife and came of age in local politics while both were working for the Dinkins administration. Dinkins, according to de Blasio, was, unbeknownst to the public, a staunch and effective crime fighter. His problem, argues de Blasio, was communications, not substance, though many who lived through the paralyzing fear of the Dinkins years would probably disagree.

Talking to Salon, de Blasio gives Dinkins credit for expanding the number of cops in New York City with the “Safe Streets, Safe City” program and for bringing the great crime fighter Bill Bratton to the fore. But neither is true.

It was City Council Speaker Peter Vallone who took the lead in expanding the police force. And in the wake of an out-of-town tourist murdered in Times Square, it was the tabloids—with screaming headlines like “DAVE, DO SOMETHING”—that forced the issue.

As for Bratton, there I played a small role. In 1992, along with George Kelling, one of the founders of “Broken Windows” policing, I interviewed Bratton for City Journal on his extraordinary success in turning around crime in the subways. Pre-Giuliani Gotham had separate police forces for public housing and the subways, as well as the NYPD. Between 1991 and 1992 Bratton used the Broken Windows approach of sweating the small stuff—i.e., arresting fare beaters—to reduce subway crime by 30 percent. But Mayor Dinkins had limited interest in Bratton’s achievement, so Bratton returned to Boston to take over his native city’s police department.

In late 1992 I had the opportunity to talk briefly with Mayor Dinkins as part of a group interested in municipal reform. I told him of Bratton’s accomplishment, but he seemed indifferent. Dinkins, like his fellow liberals, thought crime was a matter of root social causes, so policing strategies could have but a marginal effect.

It’s only now, when de Blasio wants to revise negative memories, that we are presented a Dinkins who believed policing could be crucial in making the streets safe. But in 1993, Dinkins delayed implementing “Safe Streets, Safe City” so that the newly hired cops were slow to take up their posts, where they continued to police in the old-fashioned, reactive manner. Dinkins’s emphasis was always on social work.

It’s true that some liberals were happy with policing in the Dinkins days. As one wag put it, the police didn’t bother the criminals too much and the ACLU didn’t bother the police too much. But liberal activists aside, the city has come to expect the active policing and largely menace-free streets as the norm—indeed, overall crime is down almost 75 percent over the past two decades (PDF).

Now the effective repeal of active stop-and-frisk policing at the hands of a federal judge and the increasingly left-wing City Council is putting all that in jeopardy. A de Blasio primary victory could provide an opening for the Republican nominee for mayor in the general election come November. If the Republican nominee can talk convincingly about the dangers of returning to the bad old Dinkins days, he might be able to expand the electorate and at the least make the 2013 mayoral election competitive.