It is not such a surprise when, amid the pedophilia, massacres, orgy, naked bodies smeared in blood and feathers, and painful deaths in coffins, a machine gun is trained on us, the audience. Then the shots ring out, as a light flashes on and off, the assassin’s body in jerking silhouette.

No bullets. But yes: Ivo van Hove is back in town!

There may be articles in the next few days about the shocking nature of van Hove’s staging of The Damned—a theatrical version of Luchino Visconti’s 1969 movie of the same name—at New York City’s Armory, which opened Tuesday night.

And yes, in this massive, cavernous space, the master of theatrical spectacle, directing the Comédie-Française company, both does what we have come to expect him to do and outdoes himself. After his production of Network at London’s National Theatre, the Armory offers a thrillingly large stage to open up his formidable box of tricks on.

On a grand scale, The Damned contains graphic violence, graphic sex, graphic orgiastic excess, graphic murder, Nazism in graphic tooth and claw, and—most disturbingly—child sexual abuse, scenes that stop barely short of showing that abuse in graphic detail.

“Graphic” is the performance’s guiding principle, for good and bad. Watching The Damned is like lying down with writhing snakes coated in cyanide and neon flashing lights.

On the right of the stage is a set of bleachers, with six coffins. Into those coffins go all those who die during the production. A camera inside the coffins transmits their mostly agonized deaths to a big screen in the center if of the stage. This is a piece of theater with a proudly cinematic heart.

With each death, a nameless performer deposits their ashes in an urn at the front and middle of the stage—and that urn resembles the urn that is the centerpiece of the family dining table in Visconti’s movie.

At the point of a character’s death, the camera operators who follow the actors around supply us with close-ups of us, the audience, watching on.

Above all the arresting sound and fury van Hove’s fiercest, most furious message, conveyed in silence, is a moral one about the complicity and willed myopia that abet the rise of fascism, with the faces of us—the public, the audience in Trump’s America of 2018—reflected back to us, perhaps as both warning and indictment.

That is extremely powerful, but a downside of van Hove’s bombardment of spectacle can be a failure of basic storytelling and erasure of character nuance. We see a lot, big messages and themes are loudly presented, but the characters and their stories get blurred in the onslaught.

Shock can be shocking, particularly when channeled via the powerful conceptual visions of van Hove and his partner Jan Versweyveld, scenography and lighting designer. They work on scales small (like Lazarus at the New York Theatre Workshop) and large, like his Broadway A View From the Bridge. Van Hove makes sure our eyes are dazzled, seduced, and revolted. This vivid barrage can also be muffling, numbing.

Whatever headlines and pearl-clutching become attached to it, the fundamental tone of van Hove’s production isn’t transgressive or radical.

It faithfully mirrors the content and tone of Visconti’s movie, which starred Dirk Bogarde, and it is more respectful distillation than grand reversioning of the screenplay, written by Visconti, Nicola Badalucco, and Enrico Medioli.

‘The Damned,’ 1969.

Mario Tursi/Italnoleggio/Eichberg/Kobal/REX/ShutterstockVisconti was an opera, theater, and film director. His film of The Damned, in its lighting, design, and direction, is quite clearly the work of a director—like van Hove—keen to subvert, heighten, and reshape the dramatic forms they inhabit. Visconti and van Hove in theatrical and cinematic conversation is as tantalizing as it is uncomfortable.

The primary homage to the movie is there in the center of the Armory stage, the screen on which the action on stage is shown in close-up, as the characters are followed around the stage by camera operators.

This gives us immediacy, for sure, but it also flattens characters and the story. Video designer Tal Yarden also deploys pre-recorded pieces of action, and vintage newsreel footage, of the Nazi burning of books and Dachau, for example. (In one of the play’s few funny moments, we watch one character run all over the Armory, and then outside, to see a stunned modern-day New Yorker looking back at them.)

The Damned marries both soapy dynastic drama (a vicious battle for the von Essenbeck family steelworks), with political and cultural tragedy, as this battle unfolds in Germany as Hitler and Nazism rise to power and precedence.

The most striking direct nod to Visconti is in designer Jan Versweyveld’s orange-colored floor of the Armory, mirroring the livid orange flames of the von Essenbeck steelworks that open the movie credits sequence, eventually billowing to ashy smoke.

The flames return in a later and then a final scene, alongside the infernal clanging of the factory; a forbidding dirge Eric Sleichem, the sound designer of this stage version, opens and peppers the show with. They are the licking flames of the Inferno, hell by any other name—and also a prefiguring reference to the furnaces the Nazis would eventually build to burn their victims' bodies.

In The Damned worst elements of personal and political venality and ruthlessness murderously feed each other. Everything in The Damned is poisoned, everything and everyone is damned by the end. Nazism feeds, quickens, and darkens the fall of the house of von Essenbeck.

Patriarch Joachim (Didier Sandre) is ready to cede control of the family’s steelworks, but to who? Student son Gunther (Clement Hervieu-Léger) is sensitive and vulnerable.

Then there is pedophile Martin (a squawking, transfixing Christophe Montenez), who’s also into mom-and-son incest and a cross-dresser. This last element should have been struck from the script. It’s an offensive underscoring of supposed perversity and reminded me of similarly misdrawn villains in The Silence of the Lambs and Cruising. As the most morally depraved character, Martin finds himself coziest in Nazism’s embrace.

Van Hove’s production has shocks and provocation of all kinds, moral and visual. The child abuse, creepily shot in close-up for us to watch on the screen, is carried out by Martin on his young cousin Thilde (Gioia Benenati) and another little girl, Lisa (Lucy-Lou Marino).

Truly, it’s more unsettling to watch in Visconti’s movie, but that doesn’t make it any less hard to watch on stage. One of the little girls screams (presumably as Martin abuses her). That scream goes unmet, the most terrible abuse is unconfronted—again reflecting the production’s bigger theme of the neutered response to fascism.

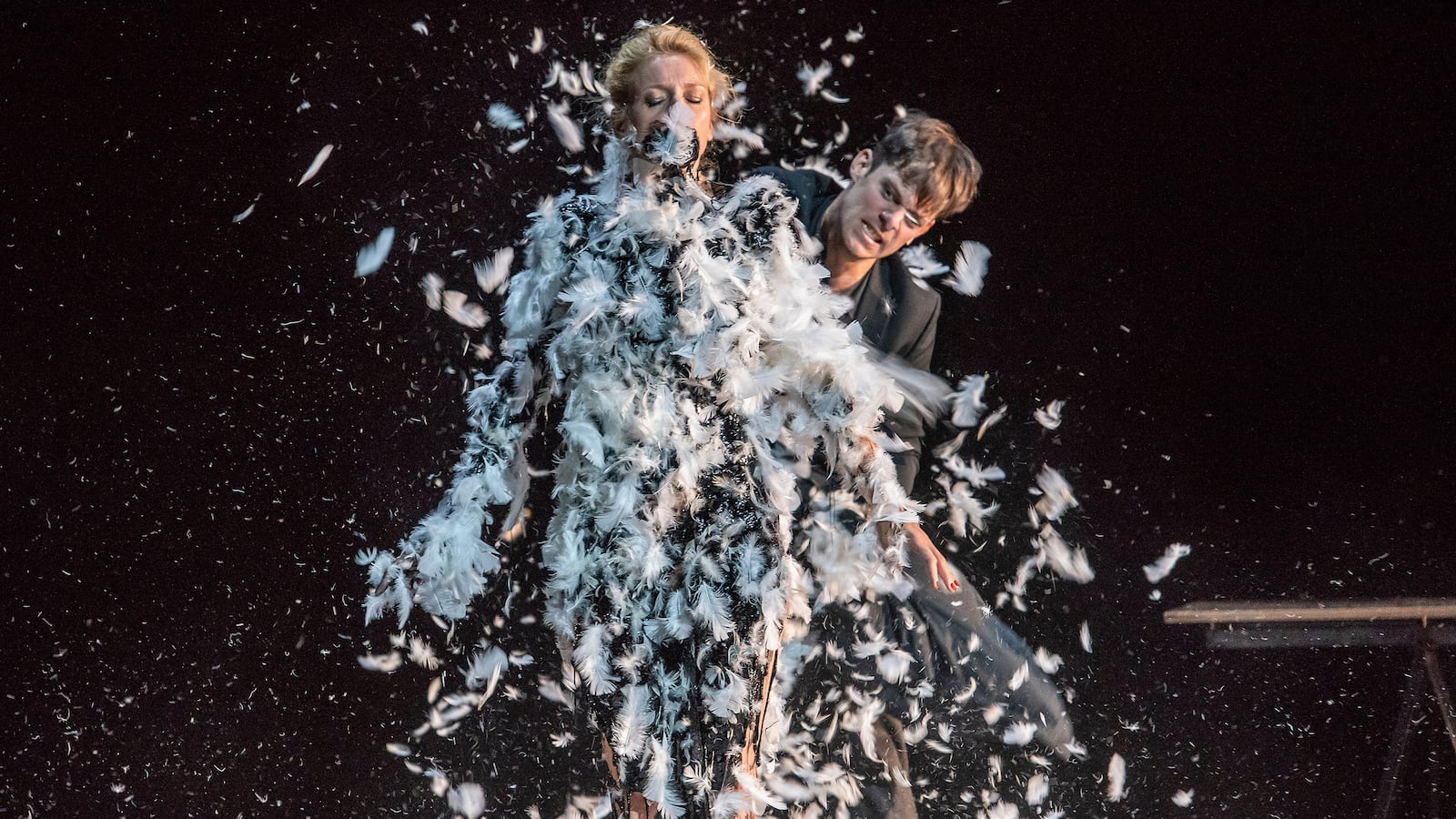

Elsa Lepoivre, as brilliantly chilling as Ingrid Thulin was in the movie as Lady Macbeth-matriarch Sophie, is finally undone by her incestuous sex with her son, and in an astonishing scene is stripped naked, tarred and feathered (those feathers eventually billow and waft towards us).

Lepoivre is not alone in her stage nudity. You will not soon forget van Hove’s take on the Night of the Long Knives, and the massacre of naked, carousing SA officers.

In Visconti’s film, this happens in a beer hall and lodgings on the side of a lake in the misty violet of early dawn. The gunfire and blood are plentiful. Van Hove has two SA officers throw beer across the orange floor, strip, swim in it, wrestle and writhe in it, while on the screen behind them we see more naked officers, in pre-taped footage, doing the same.

When the massacre comes on screen the blood of each shot corpse blooms as if on a petri dish. In person, buckets of blood are deposited on the officers.

Another family relation, Konstantin (Denis Podalydès), and SS officer cousin von Aschenbach (Eric Génovèse) will do anything to twin the family to the Nazi Party’s greater objectives.

The wholly good and ill-fated firm’s vice-president Herbert Thallman (Loïc Corbery) can see all too clearly the rise of fascism around him, and the Nazis desire to avail themselves of the steelworks; in a nod to his movie counterpart, Corbery wears a similar light green trench coat as he prepares to escape.

Visconti couldn’t train his camera on his cinema audiences, but he let his characters underscore the same point as van Hove.

“It’s all over,” Herbert says. “It was our fault, everyone’s—even mine. It does no good to raise your voice when it’s too late—not even to save your soul … Nazism is our creation. It was born in our factories, nourished with our money.”

The staging of van Hove’s adaptation, first performed at the Avignon Festival in 2016, is also an exercise in formalized ritual—another echo of Visconti’s movie. Heels click across floors, the action has a cold efficiency to it. The Damned as both movie and play aims to animate the hopelessly propulsive progression toward dictatorship.

Van Hove also seeks to make the act of theater a piece of theater in itself. On the left of the Armory stage are a set of bleachers where some actors sit when not in scenes, a set of five makeup seats and bulb-surrounding mirrors where characters dress and interact, and four mattresses, where characters occasionally throw themselves.

Beyond that, in the shadows of the Armory, are rails of clothes and helpers aiding the characters robe and disrobe. The servants we see throughout Visconti’s film, involved in their hushed ballet of picking up towels and serving food, are here six men in black stationed beside the big screen.

The main setting of the movie was the echoing von Essenbeck family mansion, which the scale of the Armory naturally evokes. Like the movie, the play opens and nearly ends with a silver-service banquet, family breakdown rather than celebration the main course.

Sophie’s last words in both movie and play are “Thank you for coming.” In the movie she says it to her wedding guests, occupying the von Essenbeck mansion now transformed into a proto-Nazi command center, with floor to ceiling Swastika banners. The family, and the family as symbol for a nation, has been utterly overrun and infected. Sophie is broken, barely sentient.

On stage, Sophie says it to the camera, to us: that implication again, that invitation to a terrible complicity. The final stunning van Hove visual—care of fruit loop Martin—is shocking, predictable, and grotesquely ambiguous.

People in the future “must know and remember,” Herbert says of the physical and moral horror the family is living through. But even if people know, what should they do? That’s the question van Hove leaves unasked and unanswered, as his cameras survey all our faces.

The silence is damning, if not yet of the damned.

The Damned is at the Park Avenue Armory, until July 28. Book here.