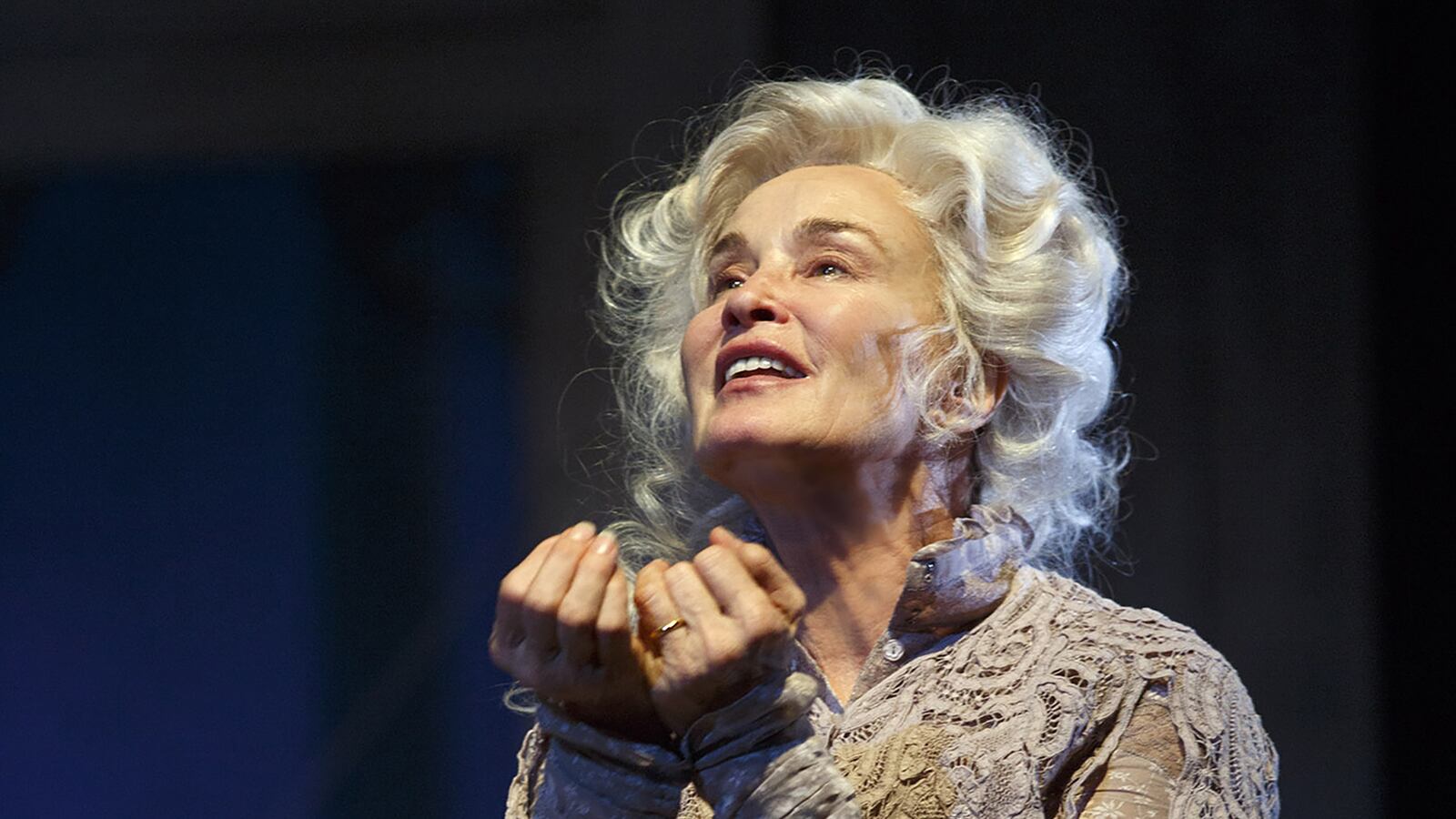

Even when Jessica Lange is not physically on stage as Mary Tyrone, in the current Broadway production of Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night, her specter hovers.

The character of Mary is the querulous fulcrum around which the other characters orbit in Jonathan Kent’s beautifully and precisely realized production for the Roundabout Theatre Company—although her husband, James Sr., sons James Jr. (Jamie) and Edmund, and an Irish maid, Cathleen, are always on thin, unknowable ice with this matriarch.

The play—nominated for seven Tonys, including for Lange as Best Actress in a play, and Gabriel Byrne as James Sr. for Best Actor—is three hours and 45 minutes long. There is only one 15-minute interval. It is not a play of feverish action. You must sit there, and listen (and listen you most certainly do, utterly rapt), as O’Neill twists and turns the characters around a family tragedy and the many distortions it has wrought over the years.

The trajectory of the play is in the title. It is a summer’s day in the life of the Tyrones, a family based on O’Neill’s own. Byrne’s character is an actor who is disillusioned with his craft and how his own career has unfolded—but could that be because his main area of concern has been Mary, as played by Lange in many shades of flighty, tender, skittish, damaged, all-knowing, and shrewish?

Alongside Mary’s addiction is James Sr.’s careworn dependability, and the sons—one possibly very sick and the other extremely reckless (John Gallagher. Jr. and Tony-nominated Michael Shannon)—rattling about the house, as a long day does indeed stretch into night and the fog rolls in engulfing the house, muffling it.

However seriously ill Edmund is, his condition is seen in light of a terrible event that befell his parents many years ago, and which led Mary to her morphine addiction.

Lange originally played Mary in London in 2000, and the modulation and feel of her performance also has echoes—abandonment, a fluttering madness, desiccated passion, a pained, very personal nostalgia—of A Streetcar Named Desire’s Blanche duBois, whom Lange played on Broadway in 1992.

The play has already won Best Revival of a play, and acting awards for Lange and Shannon at the Outer Critics Circle awards on Monday.

The success of this Long Day’s Journey… is in the fluency of its direction and performances. One watches the play unfold—its characters’ moments of volcanic rage and extreme tenderness, their meditations, personal catechisms, their justifications and shadowy histories—on what we know to be a stage, right there separate to us, and yet for the fiction to feel as immediate as a piece of immersive theatre.

We may not be being guided around the theatrically ornate rooms of Sleep No More, and forced to hover over writing desks, or lost in dimly-lit faux woodland, but the great success of Kent’s direction in Long Day’s Journey…, is that the audience is so enveloped in the travails, traumas and relentless psychodrama of the Tyrone family, we feel as if we too are there, in an adjacent room mesmerized and helpless.

The weather systems are both outside the windows of the family’s summer home, and on stage—squalls give way to tenderness, shouting and recrimination come studded with cracks of emotional thunder. The fog which engulfs the house is also present metaphorically as a muffling cloak for the family too, rooted in the past.

Tellingly, the dissonant note is Long Day’s Journey… is the cheery, inappropriate Irish maid Cathleen: her brightness and breathy gossip and trivialities are light relief in the greater scheme of the play’s heaviness.

Your patience may be tested by the back and forth—back and forth they all go, which doesn’t seem to go anywhere or lead to change—and returning from the interval, one seatmate noted to his pal, “Long day’s journey to nowhere in particular.”

Perhaps some abridging could be done, but the challenge and demand of the play is one which TV and film, and theater, rarely do: It demands we sit still, shut up, and appreciate and luxuriate in the dramatic feast in front of us.

Byrne and Lange are perfectly judged and nuanced counterweights to one another: He is lugubrious, and with all the kindness and resentment a longtime career has to someone much loved and worried over. Lange is a temperamental cat: horrible to him, and cutting to her children, then gentle, then demanding reassurance, then terribly vulnerable.

Mary is a prisoner of her own addiction, a prisoner of the demons that led her there, and her husband and children both fellow inmates and (in her mind) her jailers.

Nobody is sure the mood Mary will be in, nobody is sure if she has returned to drug addiction, nobody is sure what her thudding footsteps above mean, and nobody is sure if they can all survive what they must survive.

The toxicity in the house, and the strength of the family ties and the frays of those same ties all seem to be of Mary’s initial making and marshaling—and the complicity and fear of her husband and children have had their own tragic and deleterious consequences too. The family feels lost—in time, and in itself. Everyone is scared for Mary, of Mary, and of confronting history.

For nearly four, very special hours, the Tyrone summer house is prison, psychiatric hospital, battlefield, retreat, and life raft. It would be too much, and too easy, to say there is a happy ending, but you feel enriched to have joined the Tyrones for the storm-tossed, battering ride.