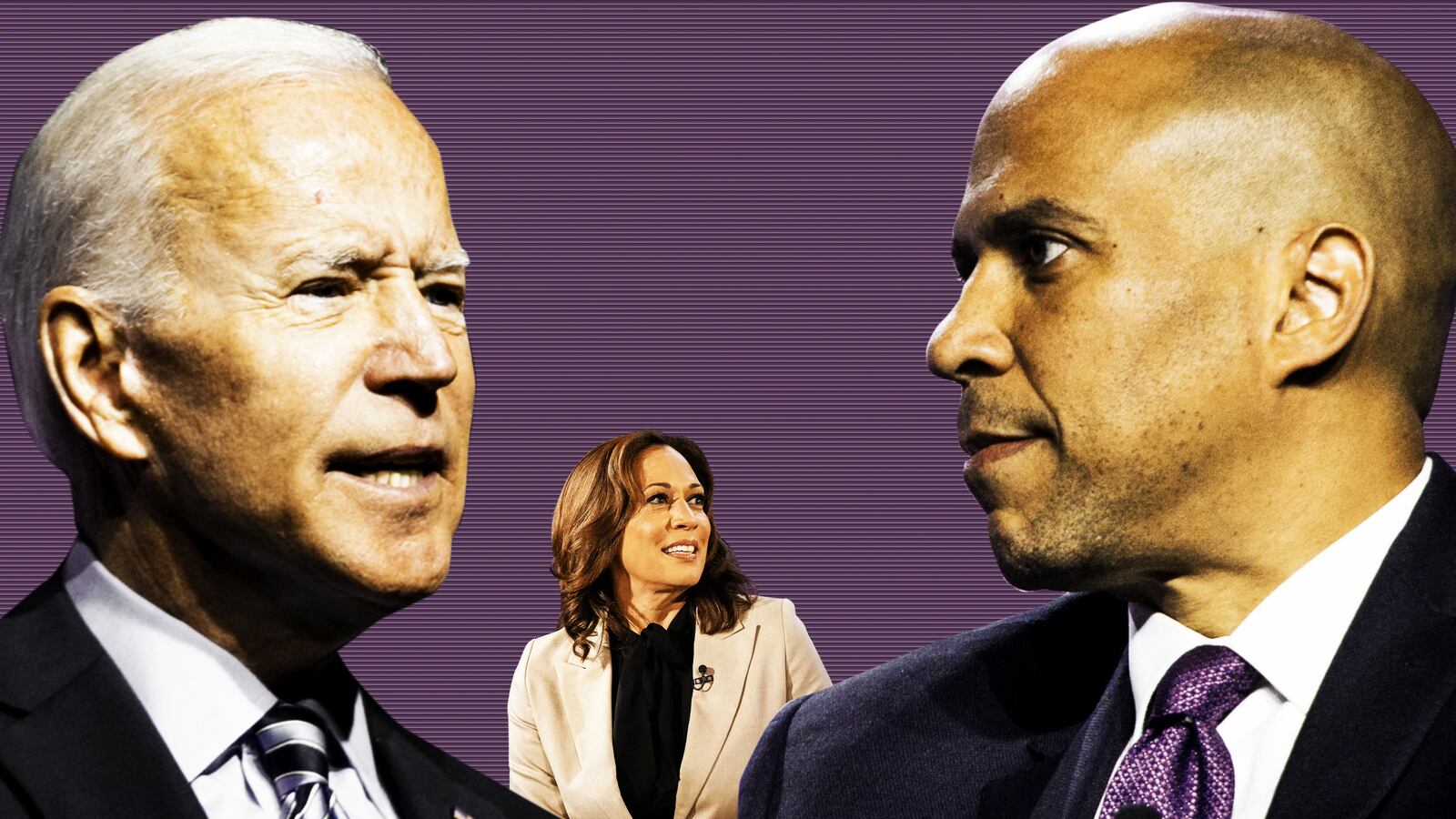

Cory Booker is ready for his moment with Joe Biden.

A week out from their appearance on the same stage at the second Democratic presidential debate in Detroit, the New Jersey senator and the former vice president traded jabs over criminal justice reform—previewing what promises to be a contentious issue among the two rivals.

Speaking to reporters after his appearance at the NAACP convention in Detroit on Wednesday, Booker referred to Biden as “an architect of mass incarceration.”

“I’m disappointed that it’s taken Joe Biden years and years until he was running for president to actually say that he made a mistake,” Booker said. “That there were things in that bill that were extraordinarily bad. I’ve been living and working now in Newark, New Jersey for 20 years and we’ve seen the devastating impact of legislation like that. That has destroyed communities.”

Booker and his campaign have spent weeks targeting Biden, sharpening attacks on his role in crafting the 1994 crime bill and characterizing Biden’s recent efforts to undo the mass incarceration caused by that law as too little too late. Whether the attacks will land in a way that propels him upward in the polls, remains to be seen.

But it was clear that Biden and his campaign were not going to be caught flatfooted for a second time. Last month, Biden found himself reeling in the first debate following an exchange with Sen. Kamala Harris (D-CA) that hemorrhaged the Democratic frontrunner’s lead.

So instead of turning the other cheek, Biden and his campaign leaned in.

"His police department was stopping and frisking people, mostly African American men," Biden said. “If he wants to go back and talk about records, I’m happy to do that. But I’d rather talk about the future.”

Hours later, the Biden campaign pounced. In a rare on-the-record attack about another opponent, Kate Bedingfield, Biden’s deputy campaign manager, said that “It is Senator Booker, in fact, who has some hard questions to answer about his role in the criminal justice system.”

She referenced that at Booker’s inauguration as mayor in 2006, he pledged to implement zero-tolerance policing which would include stop-and-frisk searches and overall police practices that earned a “D” grade from the American Civil Liberties Union in 2009. Additionally, Bedingfield referenced Booker’s initial resistance to a 2010 petition from the ACLU to the Department of Justice for an investigation into the city’s police department. In a 2014 report, DOJ found that “approximately 75% of reports of pedestrian stops by NPD officers failed to articulate sufficient legal basis for the stop” and that African-American residents in Newark were “at least 2.5 times more likely to be subjected to a pedestrian stop or arrested than white individuals.”

Booker, who has focused his presidential campaign and Senate tenure on robust criminal justice reforms, has acknowledged that he could have handled the police department better during his time as mayor.

“Even as I had strived my entire life to be a force for equity, fairness, justice and opportunity, it was obvious that some of our police practices, on my watch, were undermining not only my own values but my life’s mission,” he wrote in his 2016 book United, according to The New York Times.

There have been early signs that Booker was gradually shifting away from his “radical love” message during the Democratic primary, though his interactions with his rivals have largely remained diplomatic. But tension had been building between Booker and Biden, the current Democratic frontrunner, over the past several weeks with new force.

While Booker’s campaign declined to say whether hitting Biden on criminal justice was a possible line of attack he would use in next week’s debate, his campaign manager, Addisu Demissie, responded to Bedingfield’s statement on Twitter.

“‘For decades, Joe Biden has been working on criminal justice reform,’” Demissie wrote, quoting from the Biden statement. “That’s the problem. And that's the tweet.”