“It can’t happen here” is a turn of phrase regularly deployed as irony, a warning to citizens of nominally free societies that millions of Germans thought the very same thing even as the Nazis rose to power. Born as the title of Sinclair Lewis’s satirical 1935 novel depicting the rise of a populist U.S. president who becomes a totalitarian dictator, the unspoken rejoinder is that, “Yes, it can happen here.”

Which is why it would be tempting to watch the new documentary Karl Marx City—anchored by co-director Petra Epperlein’s search to learn if her father was an informant to or agent of the notorious East German secret police known as the Stasi—and extrapolate that the right-wing populism representing so much of the West’s current political upheaval could lead us down the miserable path taken by the German Democratic Republic (GDR), the Soviet-backed communist prison state which ceased existing upon German reunification in 1990.

But that would be a disservice to this excellent and very original film, which mostly avoids making such easy clickbait comparisons (aside from one talking head’s rather awkward comment about Facebook being something the Stasi would have found “useful”). For the most part, the film demonstrates how ideology matters far less than things like overcriminalization, mass suspicion, and censorship when it comes to the creation of a police state.

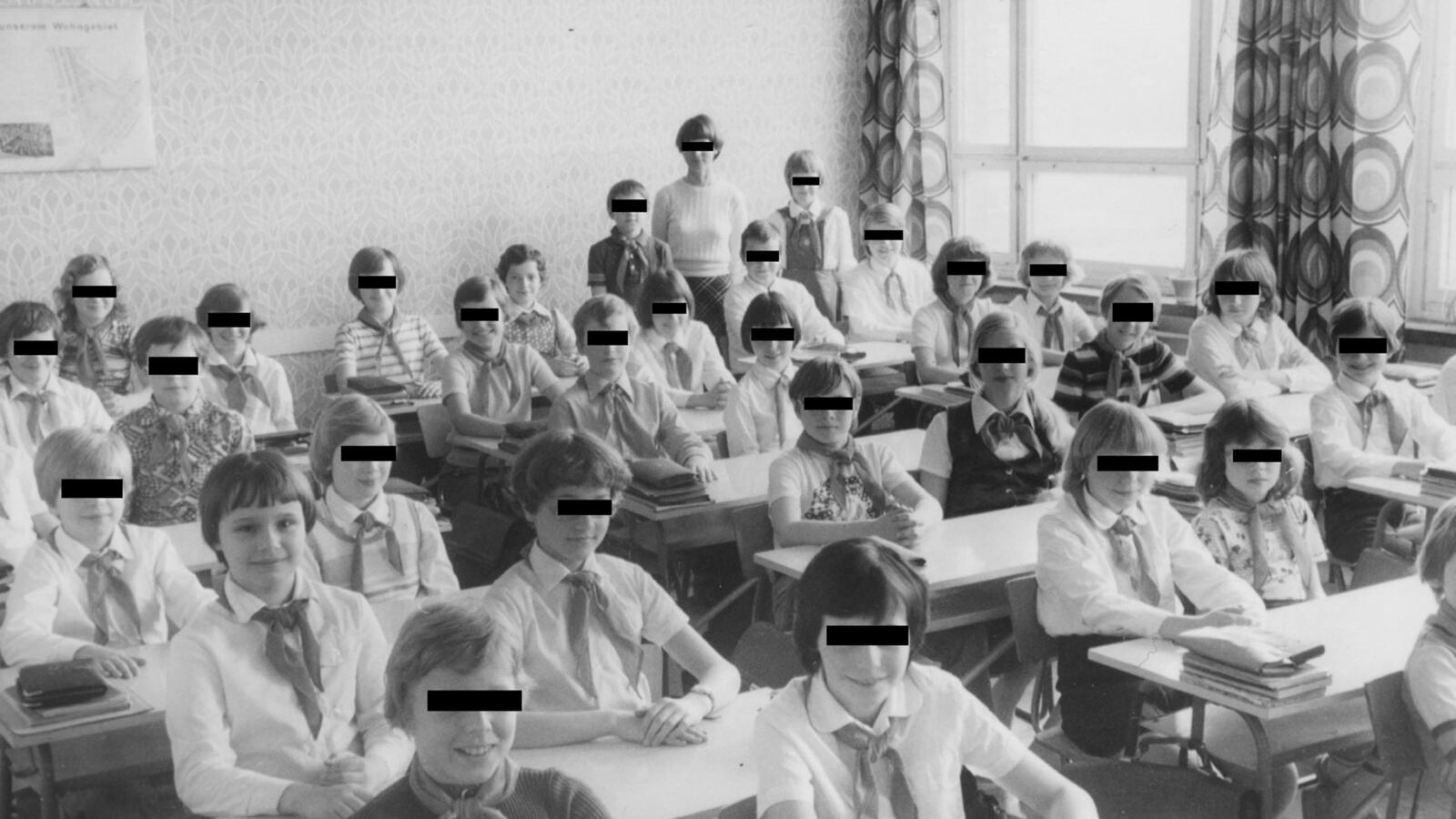

To tell a personal story in the context of the national history of an increasingly forgotten failed utopian state, Karl Marx City uses a great deal of remarkably well-preserved and time-stamped Stasi surveillance footage. As the film’s protagonist, Epperlein retraces the paths of ordinary East Germans who may not have known but likely assumed they were being watched, walking down the same unassuming streets of her home city—which shared its name with the film during the GDR era, but which is once again known as Chemnitz.

Much of the footage is frightening in its banality, such as a clip of an elderly couple innocently walking down the street, or the chilling sounds of Stasi agents sizing up an overweight visitor from West Germany: “He looks like a capitalist… A real fat entrepreneur.”

The film aptly describes East Germans as the most surveilled citizenry in human history. Indeed, those trapped behind the Berlin Wall (euphemistically called “the anti-fascist protection rampart” by the GDR government, which imprisoned its people behind the militarily fortified barrier in 1961 to stanch the exodus of citizens across its borders) were subject to relentlessly pervasive warrantless searches of their homes, mail, and personal effects. Some of these searches were done in secret, other times Stasi agents would rearrange the furniture in a target’s home as a means of intimidation. One interviewee tells a heartbreaking story of how a priest—who had enlisted him to illegally smuggle books banned as counter-revolutionary by the government—was later revealed to be a Stasi informant.

Negative comments about the government or socialism or the wretched pollution or quality of life in the GDR were reported to authorities by a vast network of informants, which included colleagues, friends, and family members snitching on each other to keep themselves on the government’s good side. A familiar East German maxim, noted in Karl Marx City, is that if three people are in a room, one is an informer. Though the Stasi tried to destroy its records in the chaos following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, over 41 million index cards and innumerable files on the lives of East Germans survive in the preserved Stasi archives.

In “a society that promised every day would be like the last,” fear, paranoia, and mandatory nationalism (children failing to express sufficient enthusiasm at GDR military parades could place the entire family under suspicion) were essential to maintaining what the film describes as the invisible control of the modern dictatorship. It is that invisible control that those of us in “free” societies should be most vigilant against today.

Edward Snowden’s 2013 revelations about the mass vacuuming of American’s personal data by the National Security Agency (NSA) are obviously analogous to the GDR’s ethos that the government can make itself invulnerable to threats if it knows everything about everyone. The GDR used the term “prophylactic surveillance” to describe its strategy of spotting troublemakers before they could create any trouble, which also turned out to be a sound business strategy for the communist East German government, which during its four-decade lifespan ultimately “sold” over 35,000 political prisoners to the capitalist Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) in the West for more than three billion deutsche marks.

It’s not just the NSA emulating tactics used by the Stasi to maintain the GDR prison state. In the name of security following the London bus and subway attacks of 7/7/05, mass surveillance of everyday life in the U.K. continues to grow exponentially almost 12 years later.

The New York Police Department didn’t need to be sold on the idea of “pre-crime,” with its recent history of suspicionless searches of innocent people, unconstitutional spying on Muslim communities, and a tactic it calls “Omnipresence.” And while there are plenty of good reasons to encourage denizens of cities vulnerable to terrorist attacks to “say something,” if they “see something,” such a mantra can foster a culture of mutual suspicion on a mass scale if it is too broadly applied. History has shown a human tendency for citizens to willfully surrender their civil liberties to the government in exchange for security and order, which is one thing the Stasi could boast that it provided to the GDR.

We are still in the very early days of the third post-9/11 presidential administration, each of which has exploited fears of terrorism to chisel away at civil liberties—including freedom of speech and freedom from unreasonable search and seizure—in the name of security. Karl Marx City wisely avoids warning against any particular modern-day political ideology or movement. It does warn how easy it is to enlist citizens as collaborators in their own imprisonment.

In the GDR, resistance to state control over any aspect of life was suicide, collaboration was survival. It couldn’t have happened without compulsory nationalism, mass suspicion, and omnipresent eyes on the public.