On March 2, Intercept co-founding editor Jeremy Scahill posted a Twitter thread condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, while also arguing that the United States and NATO were “in a dubious position to claim moral high ground in condemning Russia’s actions.”

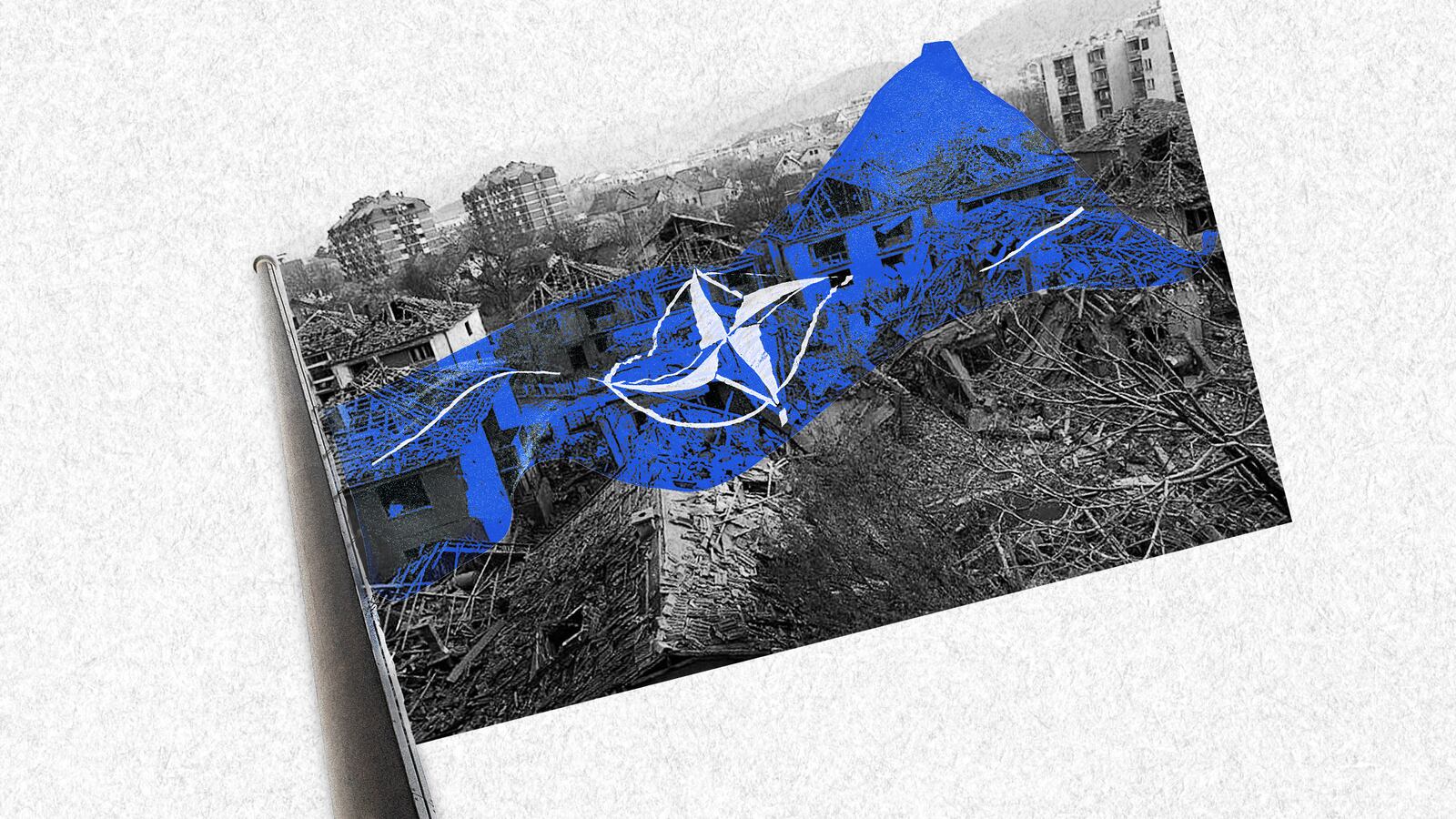

Scahill accused NATO of “similar or identical acts” of war crimes during the 1999 bombing of Serbia and Montenegro, a campaign launched in response to Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosević’s attacks against the Albanian population of Kosovo, who were fighting for their independence.

Since then, both Scahill and MSNBC host Mehdi Hasan, who retweeted the thread, have been criticized by some political scientists and ex-diplomats for downplaying Milosević’s crimes against humanity to frame NATO as little more than a defender of Western imperialism.

Not only does this narrative ignore the reasons for NATO’s intervention in the Balkans, but it’s a dishonest way of trying to convince the public that NATO shouldn’t intervene in Ukraine.

The Kosovo War was one of many conflicts in the Balkans during the 1990s, all resulting from the breakup of the communist Yugoslavian state. Beginning with the 1991 Ten-Day War, Milosević and the largely-Serbian Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) waged war against the states that declared independence from the former Republic of Yugoslavia—including Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. The JNA committed gross violations of human rights, including mass rapes and ethnic cleansing. Most infamous of all was the 1995 Srebrenica genocide, in which more than 8,000 Bosniak Muslim men and boys were slaughtered.

Milosević and the JNA launched their first attack on Kosovo in February 1998, in response to the territory’s growing independence movement led by the Kosovo Liberation Army. NATO, with the backing of the United States, negotiated a ceasefire in October 1998. But the resumption of violence in December and the failure to reach a peace agreement led to NATO’s decision to launch a series of airstrikes on Yugoslavia on March 24, 1999. The strikes were led by U.S. General Wesley Clark and a NATO spokesperson summed up the plan as “Serbs out, peacekeepers in, refugees back.” Milosević surrendered on June 11, after 78 days of airstrikes.

NATO’s bombardment, and the United States’ role throughout the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s are often held up to this day as an example of successful humanitarian intervention. That is not to say they were flawless. NATO went ahead with the airstrikes without the approval of the United Nations. And as Scahill points out, there were terrible instances of civilians and journalists killed by NATO’s intervention.

Then-UN Secretary General Kofi Annan expressed mixed feelings about the alliance’s decision, but understood why it was made. “It is indeed tragic that diplomacy has failed,” Annan said, “but there are times when the use of force may be legitimate in the pursuit of peace.”

If Scahill and Hasan wanted to question whether airstrikes are justified without UN approval, that would be part of a legitimate debate. Instead, they cherry-pick NATO’s mistakes, some of which are inevitable in the fog of war, to argue that the intervention was just a form of Western imperialism. Then, they apply the same logic to the situation in Ukraine.

But ahistorical Twitter threads are merely a symptom of a greater problem: over the past 20 years, many prominent far-left journalists and intellectuals have revealed a grievous blind spot towards the wars in ex-Yugoslavia.

Linguist and left-wing activist Noam Chomsky has repeatedly stated that Milosević’s actions were less severe than NATO said. In 2003, he endorsed journalist Diana Johnstone’s book Fool’s Crusade, a revisionist history of the Yugoslav wars that denies the Srebrenica genocide and questions the authenticity of events like the 1999 Račak Massacre, in which 45 Kosovar Albanians were killed by Serbian guards.

When Guardian journalist Emma Brockes asked Chomsky about his endorsement, he doubled down on his praise for Johnstone’s work, and compared people’s advocacy for Balkan intervention to “old-fashioned Stalinism.” In 2015, Serbian President Tomislav Nikolic honored the legendary leftist with the Order of Sretenje for his criticisms of NATO’s airstrikes in 1999.

In 1999, Australian journalist John Pilger criticized NATO in the left-wing journal New Statesman, calling the bombardment a “cowards’ war” and equivocating between Milosević’s attacks on Kosovar Albanians and the Luzane bus bombing, in which a NATO bomb struck a bus carrying civilians. In December 2004, he wrote a column calling Kosovo “a genocide that never was,” despite the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugsolavia charging Milosević with genocide (along with 65 other counts) in 2002.

In their attempts to support a larger narrative about interventions and imperialism, these left-wing thought leaders make nuance-free arguments to support a predetermined conclusion that all intervention, regardless of context or intent, is imperialism. Not only does this give their readers permission to ignore the atrocities committed by Milosević and Putin, it’s also license to ignore the suffering of the victims themselves. To this day, Serbians are uncovering mass graves of Kosovar Albanians. Where are the angry leftist tweets about that?

What’s more, their bad faith arguments could potentially make it easier for readers to accept dubious sources of information. Recently, Kremlin media outlet Redfish has spread memes intending to dupe Americans into not supporting Ukraine in its war against Russia. The most infamous of these—a map of Europe and Africa highlighting where airstrikes take place—says, “Don’t let the mainstream media’s Eurocentrism dictate your moral support for victims of war.”

Hasan and Scahill are in no way responsible for people sharing Russian propaganda. But when Russian trolls are arguing the same thing you are (during a Russian war of aggression), it calls for a little self-reflection.

It's good to be vigilantly skeptical of the drumbeat of war, as even the most righteous military intervention can lead to deadly collateral damage. But when you dishonestly omitting relevant facts to make your point, you’re not for peace. You’re just against one side.