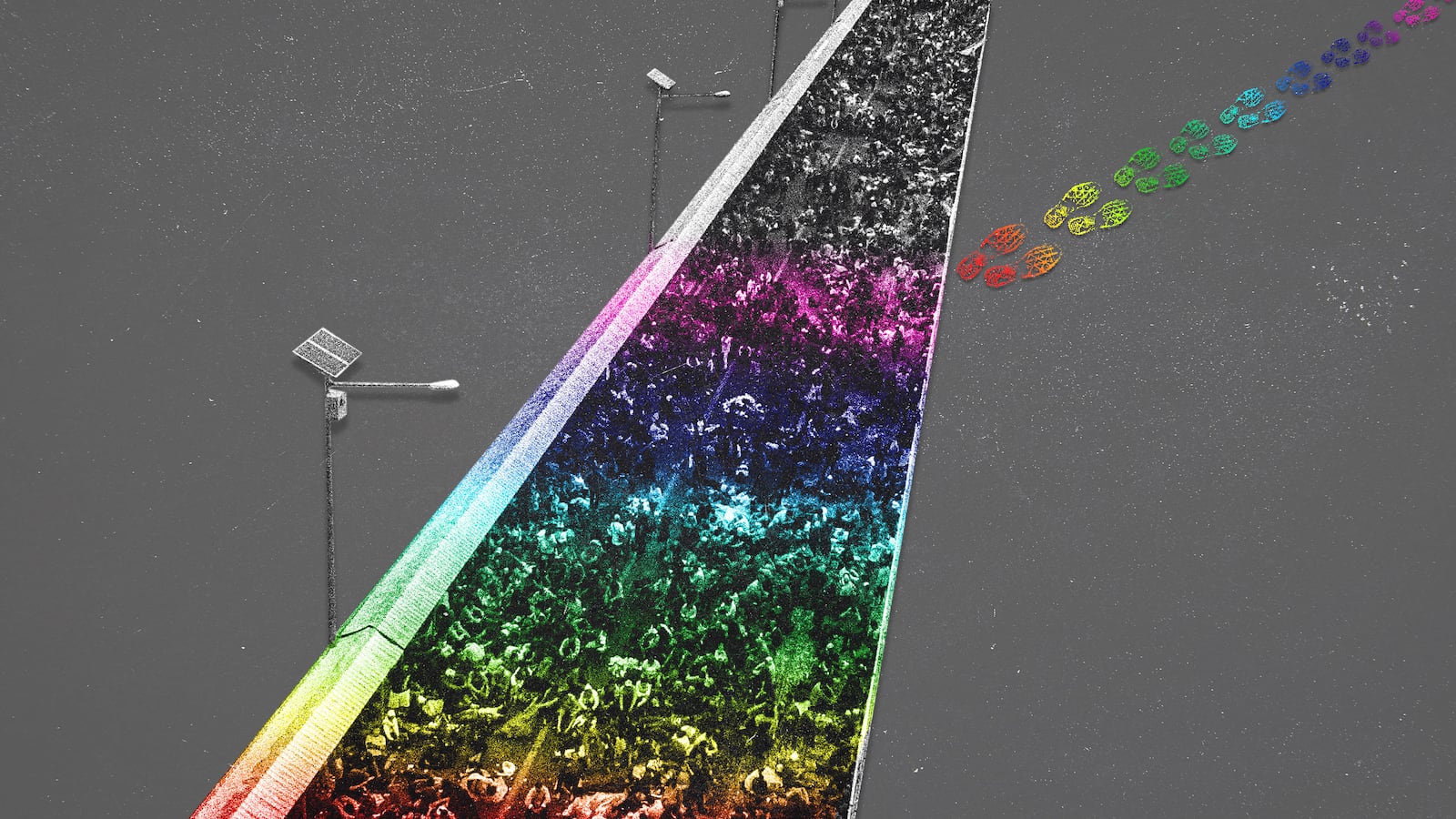

For most of the people traveling as part of a thousand-person migrant caravan in the hope of reaching safety at the U.S. border, the group represents their best chance to escape persecution, violence and criminal exploitation in their native countries. For roughly 80 LGBT Hondurans, however, the group itself became a dangerous place—dangerous enough for them to break off into a caravan of their own.

Now, American relief groups are mobilizing to ensure that their asylum claims are being taken seriously by an immigration infrastructure that has a long history of poorly handling undocumented LGBT immigrants.

“Many more LGBTQ asylum seekers are currently trapped in dangerous detention facilities,” said Jackie Yodashkin, the public affairs director of Immigration Equality, a nonprofit organization that advocates for LGBT and HIV-positive people in the immigration system. “LGBTQ people are 97 times as likely to experience sexual violence than non-trans, straight people.”

César Mejía, a gay man from San Pedro Sula, Honduras, was among the first people to join the original caravan headed for the U.S. southern border, spurred to make the 2,800-mile trek by homophobic violence and police indifference in his homeland. After he and other lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people began facing the same threats that they had hoped to flee—this time, from some of their fellow travelers—they decided to start their own journey to safety.

“We were with the caravan, the part of the caravan that is still on its way, and we left because we wanted to avoid problems,” Mejía, a 23-year-old with blonde highlights and sparkling stud earrings, told reporters in a press conference in Tijuana earlier this week. “Whenever we arrived at a stopping point, the LGBT community was the last to be taken into account in every way. So our goal was to change that and say, ‘This time, we are going to be first,’ so we left.”

Now, Mejía and other LGBT migrants are willing to wait for as long as it takes to follow President Trump’s restrictive new rules for would-be asylum seekers—even if those rules seem designed to discourage waiting at all.

“We are fleeing a country where there’s a lot of crime against us,” a transgender woman, who did not give her name, told reporters at the presser, organized by Mejía, who has emerged as a leader of the LGBT caravan members.

The LGBT caravan’s lonely exodus, first from the so-called “Northern Triangle” countries of El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, is representative of the larger problems faced by LGBT immigrants seeking asylum in the United States.

“The conditions in the Northern Triangle countries are immensely dangerous for LGBTQ people,” said Yodashkin. “According to [United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees], 88 percent of LGBTI asylum seekers and refugees from the Northern Triangle… reported having suffered sexual and gender-based violence in their countries of origin.”

According to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, a body of the Organization of American States that works to safeguard human rights in the Americans, there were 174 recorded violent deaths of LGBT people in Honduras between 2009 and 2014. The vast majority of those killings are committed with apparent impunity—of 141 violent deaths of LGBT Hondurans reported between 2010 and 2014, less than one in four was prosecuted, a trend that extends across the region.

“Our clients have survived kidnappings, rape, torture, and death threats, often perpetrated by gangs that operate with impunity or in collusion with the authorities,” said Yodashkin. “In many cases, the police themselves are the ones perpetrating violence against LGBTQ people.”

Yodashkin noted that Honduras and El Salvador have the highest and third highest per-capita murder rates, respectively, for transgender people anywhere in the world.

Although some legal protections exist to protect LGBT people in the Northern Triangle, they are largely trumped by loose enforcement and a bottom-up police structure that puts the most power in the hands of local law enforcement, many of whom are involved in criminal activity themselves.

That fact, coupled with Honduras’ Law on Police and Social Coexistence, legislation passed in 2001 that gives police wide-ranging authority to arrest anyone who “violates modesty, decency and public morals” or who “by their immoral behavior disturbs the tranquility of the neighbors,” makes LGBT people in Central America, particularly trans people, legally helpless.

“In Honduras, the simple fact of being trans, being an advocate, being part of this society, is criminalized,” one trans woman told the IACHR.

But the journey to escape that persecution can often amount to a leap out of the frying pan and into the fire. While they were traveling with the caravan, Mejía told reporters, LGBT migrants were denied food, access to bathing facilities, and even medicine and sanitary napkins.

It was only after entering Mexico City, where local media caught wind of their plight, that organizations that provide assistance to LGBT migrants began to reach out.

“When we entered the Mexican territory, those organizations began to help us,” Mejía told reporters. “We did not contact them. They learned from our group thanks to the media like you and decided to help us.”

It was with that assistance that the LGBT migrants in the caravan—who numbered at least 120, according to an informal headcount—were able to travel by bus to Tijuana, making it to the U.S. border weeks ahead of the main caravan.

“We want to do things in order, in the right way," Mejía told reporters, explaining that the majority of those in the group were hoping to claim asylum, pointing to the dangerous conditions for LGBT people in the Northern Triangle as evidence that they credibly fear for their lives if returned. “We are waiting for our representatives” to help go through the legal asylum process.

Despite recent hurdles placed in front of asylum seekers from the Trump administration, which has tightened restrictions on where, when and for what reason a person might be granted asylum in the United States, LGBT people fleeing persecution are still eligible for asylum as a class. But a massive backlog in asylum applications means that LGBT would-be asylees, who typically have access to even fewer resources and options for legal counsel than the typical asylum seeker, are left in limbo for months.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, Trump ran as a (literally) rainbow-flag-waving ally of LGBT people. During his acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, Trump vowed to do “everything in my power to protect LGBTQ citizens from the violence and oppression of a hateful foreign ideology.”

Despite that promise, the Trump administration has reliably enacted policies that have made LGBT people at home and abroad less safe, particularly transgender people. Ten days into his presidency—the same day that the White House released a statement vowing that President Trump would be “respectful and supportive of LGBTQ rights”—the Education and Justice Departments issued a joint letter rescinding a 2016 Obama administration guidance that had protected transgender students’ access to appropriate restrooms and locker rooms under Title IX’s ban on sex discrimination in public education.

The president has also signed an order barring transgender people from serving in the U.S. military, rescinded protections for transgender people in the prison system that allowed them to be held in populations that correspond with their gender identity, and, according to Bob Woodward’s book Fear: Trump in the White House, referred to gender reassignment surgery as getting “clipped.” The administration is also reportedly considering narrowly defining gender as a biological, unchangeable condition determined by genitalia at birth—essentially wiping trans identity out of legal existence.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services does not maintain statistics on the stated reason behind asylum claims, but the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has noted a global increase in the number of LGBT refugees and asylum seekers, and a 2015 report from the Human Rights Campaign and the LGBT Freedom and Asylum Network estimates that roughly five percent of would-be asylees enter the U.S. “based [on] persecution of sexual orientation or gender identity.”

The United States is a popular destination for those seeking protections from anti-LGBT discrimination and violence, particularly for those fleeing Central America. As the domestic political climate for LGBT people in the U.S. has become more tolerable, more LGBT people abroad see the United States as a safe haven to escape persecution.

But in the rush to enter the United States in search of protection, LGBT migrants who enter the country illegally risk exposing themselves to different dangers—this time, in the country where they thought they would be safe. Physical and sexual violence against undocumented immigrants held in Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention centers is frighteningly common, according to Human Rights Watch, particularly for transgender detainees who are frequently not housed in sections corresponding to their gender identity.

In May, Roxsana Hernández, a transgender Honduran woman, died while in ICE custody in a New Mexico detention center after being held in a hielera, or “ice box,” a facility known for its frigid temperatures, for five days. The temperatures exacerbated pre-existing pneumonia, complicated by her HIV-positive status. The Transgender Law Center called Hernández’s treatment part of a pattern of “rampant physical and brutal treatment” of transgender women in ICE facilities.

“Paired with the abuse we know transgender people regularly suffer in ICE detention, the death of Ms. Hernández sends the message that transgender people are disposable and do not deserve dignity, safety, or even life,” said Isa Noyola, deputy director at Transgender Law Center.

As of June 30, 2018, ICE has 72 self-identified transgender detainees in custody, spread across 13 facilities nationwide. That represents an increase from 2017, when there there were, on average, 50 transgender detainees nationwide.

Reports of questionable conditions for LGBT detainees in ICE facilities have even reached Congress. Five days after Hernández’s death, 37 members of Congress signed a letter to Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen citing concerns of “disturbing” accounts of violence, isolation, and abuse of LGBT people held in ICE detention.

“These individuals, particularly transgender women, are extremely vulnerable to abuse, including sexual assault, while in custody,” the signatories, all Democrats, said in the letter, noting that at the time, four of the 17 facilities in which transgender women were detained are were all-male facilities.

Dani Bennett, an ICE spokesperson, told The Daily Beast that decisions relating to where an undocumented immigrant may be detained are made on a case-by-case basis, and take a transgender individual’s preference into account.

ICE, Bennett said, is “committed to upholding an immigration detention system that prioritizes the health, safety, and welfare of all of those in our care in custody,” including LGBT detainees. Bennett also pointed to the opening of a dedicated unit for transgender women in the Cibola County Correctional Center in New Mexico in 2017, which has a 60-detainee capacity.

“ICE trained facility medical and detention staff in best practices for the care of transgender individuals; hired a dedicated Custody Resource Coordinator to ensure detainee access to care and services; and facilitated partnerships with local transgender organizations for peer support and other services and programming,” Bennett told The Daily Beast. Furthermore, under President Barack Obama, ICE issued a transgender care memorandum, outlining best practices for placement and care of transgender detainees. That memorandum, Bennett noted, remains in effect under President Trump.

Outside of dedicated housing units, however, “transgender detainees may be housed in any areas where general population detainees are held.”

On the southern side of a growing wall of concertina wire, however, LGBT migrants still hold out hope that their asylum claims will be respected, and that they will, at long last, be treated with respect.

“We are just thankful we arrived healthy and in all in one piece,” Mejía said.

—with Spanish translation by Pilar Melendez