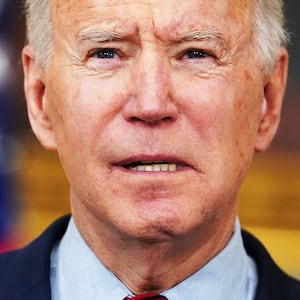

Just after noon on Thursday, President Joe Biden and a bipartisan group of 10 senators emerged from the White House and announced they’d reached a deal on a sweeping infrastructure package.

The group triumphantly declared their agreement was proof that Washington could, in fact, work. "We can use bipartisanship to solve these challenges," said Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ).

Progressive lawmakers generally disagree with Sinema’s assessment, but on Thursday, they expressed a willingness to play along with it as a necessary evil—while at the same time throwing all their firepower into what they’ve wanted all along: a multi-trillion-dollar vehicle for Democratic priorities that would pass without any GOP support.

The tentative agreement struck by Biden and the senators calls for just shy of $600 billion in new spending on roads, public transportation, water systems, broadband, and more, paid for not by tax hikes but by the Beltway equivalent of coins in the couch—unspent federal funds, sell-offs of oil, and the like.

What it doesn’t include is most of what progressives are most excited about: universal paid sick and child leave, free pre-K, and the most ambitious climate proposals ever to go through Congress. They had worried these items would fall by the wayside in order to get a bipartisan deal.

“We're not going to get left holding the bag,” said Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA). “There is no half a deal, or 10 percent of a deal, that covers roads and bridges and leaves everything else behind. There is one infrastructure deal, and it may take multiple votes to get there, but it’s one deal.”

But Democratic leaders have coalesced around a strategy that could keep progressives—and perhaps moderates—happy: pass the bipartisan deal on its own, while enacting what progressives, and Biden himself, want to see through a special process called budget reconciliation. That process would allow a bill to pass with a simple majority. And Biden said on Thursday that he wouldn’t sign the former unless the latter was also on his desk.

The gambit, which has won praise from all corners of the party, is keeping the family together—for now.

There are clear fissures, especially on the left, that could doom the delicate legislative choreography that Biden and the Democratic leaders have laid out.

One issue threatening the agreement is the overall price tag. Progressive lawmakers say a combined package that falls short of $6 trillion worth of spending and investment is a non-starter.

“If the reconciliation package that comes is north of $5.4 trillion, then, you know, things are looking good,” Rep. Jamaal Bowman (D-NY) told The Daily Beast. “If it's not, if it's sliced, then, you know, it's unacceptable and we're playing games and we're not meeting the moment of what needs to be done in our communities.”

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) was even more stark. “If you asked me, I think this should be a $10 trillion package, or at least part of a larger $10 trillion climate strategy,” she said.

Those early markers from the left indicate just how difficult it will be for Democrats to pull off what could be their signature achievement of the Biden era. They are staring down what amounts to a legislative death trap: in the span of a few weeks or months, Democrats will have to write two, massive, multi-trillion dollar bills, put them through the legislative wringer, corral 60 Senate votes for one, hold on to 50 Democratic votes for the other, and squeak by in the nearly-split House on both.

Failure on one thing will doom the entire project.

Thus far in Biden’s presidency, it’s been the moderates, like Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV), who have shown the willingness to use the leverage afforded by a 50-50 Senate and nearly-split House to make or break legislation. But progressive activists have long been hungry for their lawmakers to play hardball, and there’s a sense that the infrastructure package will be the left’s biggest chance to make a mark on a landmark bill. They certainly have the numbers to impose their will.

The conversation among progressives hasn’t developed that far yet. Many are still digesting the bipartisan deal, the toplines of which were released by the White House on Thursday. But if they are going to hold their noses to vote for it so they can negotiate a bigger reconciliation package, the early indication was that the deal stank.

The chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA), told reporters on Thursday that she didn’t like what she’s seen so far—she called it “a lot of smoke and mirrors”—and indicated that progressives “can’t waste a lot of time” on the bipartisan deal.

“I don't have a lot of faith in this bipartisan piece,” Jayapal said. “But if we can agree on the bigger reconciliation package and there’s nothing objectionable in the bipartisan piece, that’s one thing.”

Ocasio-Cortez said some of the details in the plan were “somewhat alarming,” but she sounded open to working on the particulars. “They are details,” Ocasio-Cortez said, “so I think there's a potential to negotiate and work around them.”

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), a liberal but by no means in Bernie Sanders’ wing of the party, was blunt with his assessment: he told a CNN reporter that the bipartisan framework was “pathetic.” And his colleague, Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT), said the bill has closer to 20 votes than 60.

It speaks to another issue for Biden and Democratic leaders. It’s not just the most progressive lawmakers who are skeptical of a bipartisan deal. Some might be the loudest—and perhaps the most willing to entertain threatening a bill in order to get what they want—but there are rumblings in the caucus that more moderate members aren’t sold on the bipartisan group’s framework. Paired with a weak reconciliation bill, such a mix could cause trouble.

“I want to see a 21st century infrastructure plan,” said Rep. Seth Moulton (D-MA). “If we're just filling potholes in 1950s highways, I’m not sure I’ll go for it.”

But there’s also no guarantee that the moderate flank of the party will get anywhere close to the $6 trillion mark that progressives want to see on a reconciliation-driven package. Privately, many don’t buy the idea that this figure is close to realistic, and they view the figure more as an opening bid in negotiations.

A fear among some progressives is this process will produce a subpar transit bill and then a pared-down jobs and family policy bill, heavily influenced by moderates like Manchin and Sinema.

“When we talk about compromise, it requires some squeamishness and the compromise here is that if Manchin wants this bipartisan bill, if he wants to get on this bipartisan bill, he's gonna have to give a little on the reconciliation bill,” said Ocasio-Cortez.

As hard fought as a reconciliation bill will be, it’s not a given that even the more limited infrastructure deal will come together.

Still, a framework is in place, and the White House will continue negotiating with senators on the details.

The bottom could fall out at any time if they hit a snag on one of any number of thorny points. If they reach a deal, however, some Democrats say the entire party should look at success and see just that.

“With this bipartisan deal and a reconciliation package, President Biden will have spent around $4 trillion on his priorities in his first year,” said Jonathan Kott, a former top aide to Manchin and Sen. Chris Coons (D-DE), a close Biden ally. “How can any Democrats—progressive or moderate—not be happy with him?”