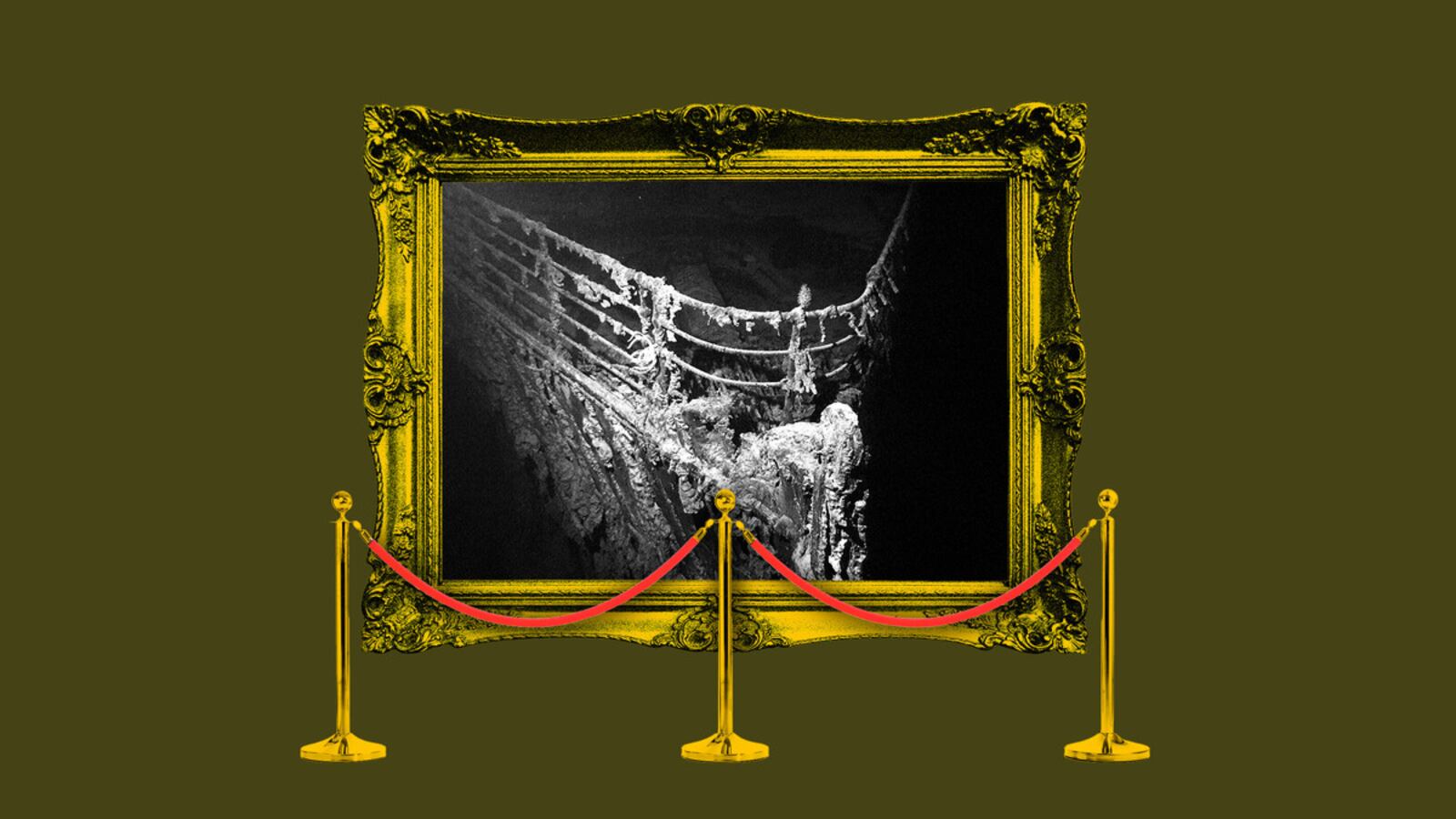

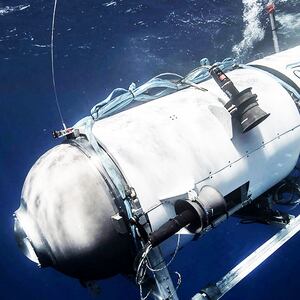

The submersible that went missing after plunging deep into the Atlantic on Sunday has triggered fiery backlash from some descendants of those who boarded the RMS Titanic 111 years ago, with relatives saying that tours of the ill-fated ship should not be happening in the first place. In their view, the site should be treated with “more respect,” in memory of those who perished there.

The underwater expedition to the Titanic’s wreckage—regarded by some as a watery “graveyard” for the 1,496 passengers and crew killed in the disaster—went awry shortly after the submersible launched its mission off the coast of Newfoundland with five people on board. The vessel lost contact with the support ship after just an hour and a half, and has not been heard from since.

Equipped with only 96 hours of oxygen, the adventure of a lifetime has now spiraled into a heart-pounding crisis that has garnered headlines around the world—and triggered an outcry from families who have raised ethical concerns about such tours.

“I think it’s disgusting, quite honestly,” 69-year-old John Locascio, whose two uncles perished after boarding the Titanic in 1912, told The Daily Beast. “I would want it to stop, to be perfectly honest. There’s no sense of it. You’re going down to see a grave. Would you want to dig up your uncles or aunts to see the box? That’s basically what I compare it to. There’s no reason for it.”

Locascio’s uncles, Alberto and Sebastiano Peracchio, were reportedly working as waiters in one of the ship’s restaurants at the time. They were only 17 and 20 years old when they lost their lives, according to the Locascio family.

“They died a horribly tragic death. Just leave the bodies resting. They don’t want people down to see them. Just leave well enough alone. I believe with what happened with the submersible, I wouldn’t be surprised if the Titanic said to herself: ‘I think I'm getting tired of these people coming down to look at me,’” he said.

“What do you want to look at, you want to ogle?,” he added. “Where is the logic, where is the sense in it all?”

Alberto and Sebastiano Peracchio

Angelica HarrisBrett Gladstone, whose great-great-grandmother and great-great-grandfather, Ida and Isidor Straus, died in the 1912 disaster, told The Daily Beast: “I’m not someone who believes in bad karma, and that people who go down in submersibles are subjecting themselves to bad karma because they’re going down to see a graveyard up close with unburied people. But the act of going down there should be a regulated procedure.”

“There should be restrictions, and there should be some degree of honor and respect given to those whose bodies remain there—or whose souls remain there if their bodies no longer exist,” Gladstone added. “I’m not wild about the idea of these tourist packages for a quarter of a million dollars, but if they’re going to do it, it should be regulated because I think it’s a dangerous experience to go down there, and if too many people go down there the site can be disturbed, endangering what’s left in terms of keeping it pristine and in its original condition.”

Shelley Binder, whose great-grandmother Leah Aks, and great uncle, F. Phillip “Filly” Aks (Leah’s son), survived the disaster, told The Daily Beast that she was praying for the safe rescue of those aboard the submersible.

Binder told The Daily Beast that she hoped there was a way to respectfully and scientifically investigate the site, as “there is still so much to discover, and what is left is collapsing in on itself. It won’t be there forever. But it feels in bad taste to travel there just to gawp. It reminds me of rich people hunting endangered species because they can afford to.”

The first photo taken of Leah Aks, right, her husband, and their baby Filly following their dramatic rescue from the Titanic.

Family HandoutBinder does not think the site should be any kind of travel destination. “If you have all that money, and if you have fallen for the allure and romanticism of the Titanic story, why not give your money to those scientists and researchers who can help us understand more about it, or fund the preservation of artifacts, or see that those artifacts are properly obtained and maintained?”

Binder told The Daily Beast that she knew she was speaking from the fortunate position of someone whose family members had survived; she knows “many others” whose family members had perished, and feel very differently. “I feel for them, and really feel I must defer to them. 1496 human beings—men, women and children—died that night in that area in the freezing cold. We must be sensitive to that before we turn it into a tourist destination of any kind.”

“We should let those people down there lie in peace”

The story of the Peracchio brothers was documented in a book by Locascio’s wife, Angelica, who described holding a softer position on the Titanic tours in an interview with The Daily Beast.

“Everyone has the right to their own opinions about how they feel, if people want to spend that kind of money and go down, that’s up to them. Me, personally? I don’t think I would be able to go against my family members. Their feeling is: Enough is enough. Leave her [the Titanic] alone,” she said.

“The idea is that they are dead and the Titanic is sacred ground. And just like you would go to a cemetery and stand on firm ground to visit a loved one and put flowers on their grave, Titanic is the same thing. It is still a grave.”

T. Sean Maher, whose great-grandfather James Kelly, of County Kildare, Ireland, died in the 1912 disaster, told The Daily Beast that though his relative’s body had been recovered and buried at sea, he still considered the Titanic to be a mass grave site—and not something that should be any kind of travel destination.

“It’s tremendously sad if some people may have lost their lives in that manner, but in my opinion they shouldn’t have been there in the first place,” Maher told The Daily Beast of those who had gone to view the site in the submersible.

“Plenty of people passed away down there [in 1912], and I don’t think should be dealt with as a tourist attraction,” Maher told The Daily Beast. “I think the Robert Ballard expedition that located it [in 1985] was fine because nothing was tremendously disturbed. But I am not comfortable with people going down and viewing it as a tourist attraction. The Ballard expedition discovered where the Titanic was, and now we know. It is what it is. It’s down there. That’s where all those people lost their lives. That should be it. It should be left just as it is. We should let those people down there lie in peace.”

Kelly’s loved ones never saw his body, but his personal effects had been sent on to his wife, Maher said.

“Almost like Disneyland”

Mark Petteruti, a gift shop owner in Massachusetts, grew up listening to stories his mother would share about his grandmother, who survived the Titanic disaster at 24 years old.

“My grandmother survived but she never wanted to think about it. She never wanted to go on a ship again,” he said. “She got in the last lifeboat, number 15, and it was piled in with people and she survived. She always had PTSD and she would wake up in the middle of the night screaming, thinking about all the people who died around her.”

Asked about the submersible tours of the wreckage, Petteruti said he feels “like it’s a graveyard, all those people who died with all their remains are down there… now it’s almost like Disneyland with all the people going down there to look.”

“It’s such a tragedy, I can’t believe people would pay $250,000 to look at it,” he said—referring to promotions of the tours that were on the website of OceanGate Expeditions, the company behind the missing submersible. (OceanGate Expeditions did not respond to a request for comment from The Daily Beast by the time of publication.)

“She had a really rough time and she never wanted to go back on a boat, and the sad thing is she was from Ireland, and she never went back to see her folks again because she didn’t wanna get on a ship,” Petteruti said. “I’m sure they were curious, and they wanted to see the Titanic and all, but it just seems so dangerous. Is it really worth it?”

Isidor, left, and Ida Straus

Public DomainThe story of Brett Gladstone’s great-great-grandmother and great-great-grandfather became famous after Ida declined to escape via lifeboat to remain with Isidor, reportedly saying, “Isidor we have been together for all these years. Where you go, I go.” She gave her maid her fur coat saying she no longer had any use of it. The couple was last seen on the deck of the boat arm in arm. A memorial statue of the couple is located in New York City at the intersection of Broadway and West End Avenue at W. 106th Street.

“My great-great-grandfather’s body was found floating with a locket around his neck that the family still has, but my great-great-grandmother’s body was never found,” Gladstone told The Daily Beast. “So, her body lays down there today—the site is a graveyard for my great-great-grandmother and so many others. I’m a little bit uncomfortable with people making money over diving down and spending what I understand to be a quarter of a million dollars to go down in these submersibles—because it is a graveyard and it should be treated as such.”

“There are still things to be investigated. Let’s do it respectfully”

Shelley Binder told The Daily Beast that her great-grandmother Leah was 18 at the time of the Titanic’s sinking, and a new mother to Filly, then just 10 months old. (Shelley’s grandmother was born 11 months after the disaster.) After Robert Ballard’s discovery of the wreck in 1985, Filly had said he wished “people would leave the ship alone,” Binder recalled.

Leah and Filly were separated in the mêlée of the tragic evening, with Leah making it on to the rescue vessel, the Carpathia, believing her son was dead. He was not, and without her knowing had also been deposited onto the vessel with another woman taking care of him. Mother and son were finally reunited—the captain of the vessel having “played Solomon,” as Binder puts it—in front of a group of society women including Madeleine Astor, who gave Leah her scarf saying, “Your baby looks cold.”

Shelley Binder as a child (on floor) with my Grandmother Sara Carpathia Aks (Leah’s 2nd child born in March of 1913) in the middle—named in gratitude for the rescue ship and Captain Rostron of the Carpathia), and Leah Aks (on right née Rosen).

Courtesy of Shelley BinderBinder’s great-grandmother was one of 712 survivors. “I know, from first-hand knowledge, how they suffered terribly for the rest of their lives,” Binder told The Daily Beast. “Afterwards, my great-grandmother was in and out of a mental institution suffering from what she called ‘nervous collapse.’ My 92-year-old father remembers her sitting him down in 1960 to tell him she could never get away from the sound of people dying in the water. She remembered it all through her life. She could never reckon with that. It tortured her. She was traumatized by it for her whole life, although she clawed her way back to some sort of life in the years that followed with her husband, my great-grandfather.”

Binder paused, and laughed. “Actually, in 1923, my great-grandmother sailed back to London for a wedding—and I am not making this up—between my great aunt Rose and a man named Jack.”

Leah died in 1967, and Shelley is forever aware that she quite literally owes her own life to Leah’s successful battle for survival that night.

“I knew her for the first eight years of my life, and got the measure of this amazing woman who had the gumption and courage to take a chance to fight for her life,” Binder told The Daily Beast. “I don’t think she would want people to see the site in a touristy way today. If you’re paying your respects on the surface of the ocean, that’s fine. And there are still things to be investigated and learned at the site, but let’s do it respectfully, not encourage tourists to just go look at it.”