Once, for an article, I brought the popular New Orleans trumpeter Kermit Ruffins to a two-story red-brick home in the Corona section of Queens, New York that, since 2003, has been the Louis Armstrong House Museum. Armstrong, the greatest New Orleans trumpeter of them all, maybe the greatest American musician of all time, called that place home from 1943 until his death in 1971. Back then, Ruffins told me, “In the Lower Ninth Ward, where I grew up, we were listening to the Commodores and Michael Jackson. When I first heard Armstrong on the radio, I was a teenager already. Still, I didn’t know who he really was.”

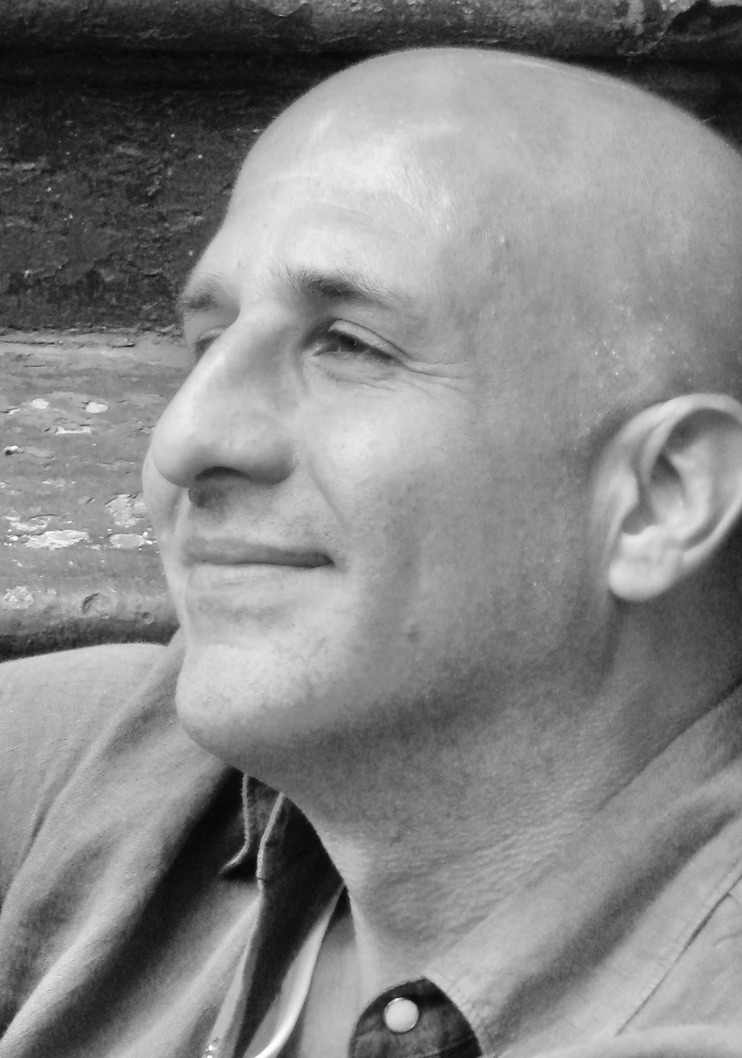

With “Louis Armstrong’s Black & Blues,” a documentary now streaming at Apple TV+ and in select theaters, director Sacha Jenkins addresses that very question—who was Louis, really? His was a similar arc of discovery. When Jenkins, who most recently directed films about seminal hip-hop group Wu-Tang Clan and the controversial punk-funk star Rick James, began this project, “I knew about as much as your average public-school kid in New York City knew about Louis Armstrong,” he told me in an interview. Armstrong’s world seemed anachronistic to his hip-hop-inflected one, maybe even at odds with it. Yet as he immersed himself in not just in Armstrong’s music but in his life experiences, Jenkins found that the trumpeter’s environment “reminded me of the people I grew up with,” including his former high-school classmate, the rapper Nas, who voices Armstrong’s written reminiscences in the documentary.

The voice of trumpeter Wynton Marsalis arrives early in the film, describing Armstrong’s “electric virtuosity.” Marsalis, who has championed Armstrong’s legacy from his pulpit at Jazz at Lincoln Center, was also resistant to Armstrong’s legacy in his youth. “I could not appreciate Armstrong,” he says in the film. Until he tried playing along with Armstrong’s solos. And before he considered the context of Armstrong’s life, he, too, had bought into the notion of Armstrong as indicative of the “Uncle Tom-ing” he saw while growing up in New Orleans.

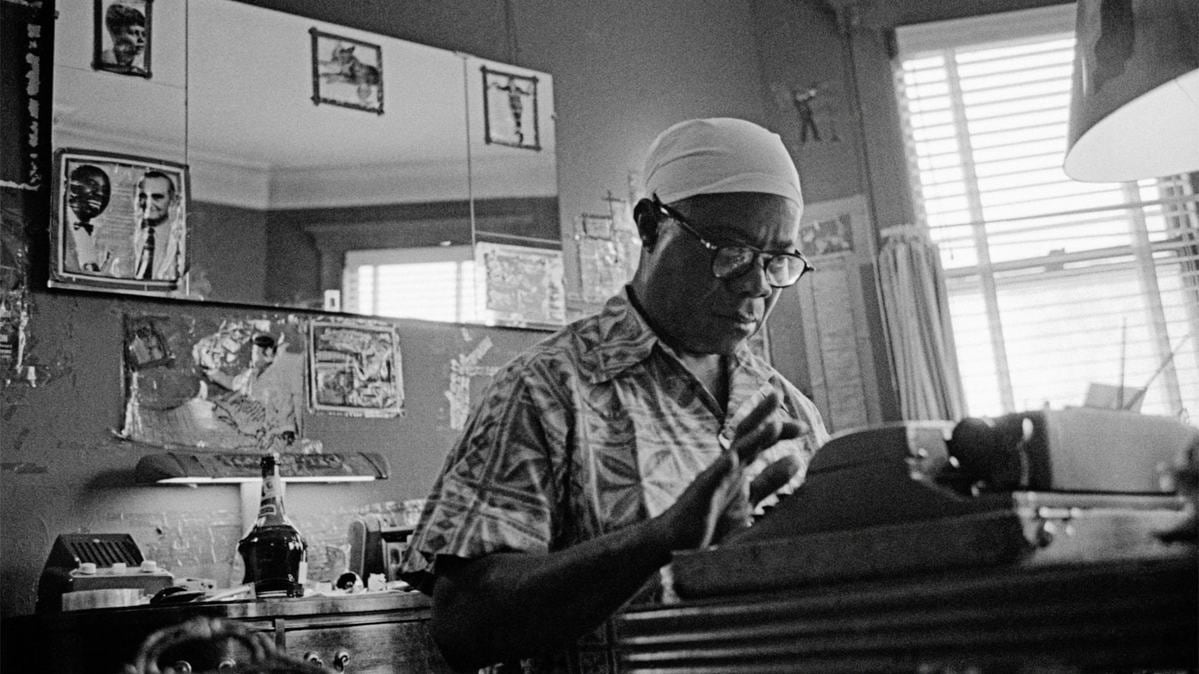

With his film, Jenkins confronts the complexities involved in understanding Armstrong’s identity, and the misunderstandings surrounding it. Here, the story leans heavily on archives so voluminous that, beginning next spring, they will be stored in a new Armstrong Center across the street from the Queens house. Much of the archival material came from the trumpeter himself. On the dual Tandberg reel-to-reel tape recorders set into a paneled wall in Armstrong’s beloved upstairs study, he taped not just music (he was ahead of the curve regarding mixtapes) but also everyday conversations. In one of the film’s artfully employed voiceovers (we never see talking heads) Ricky Riccardi, the museum’s Director of Research Collections, author of two Armstrong books, and a consulting producer here, says: “Armstrong knew that one day they were going to write about him in history books. He wanted to make sure all sides of him—good bad, ugly—were going to be captured and preserved by himself, not by anybody else.”

The power and ingenuity of Armstrong’s playing and singing course through Jenkins’s film—there’s plenty of impressive footage, including the riveting solo he inserts into “Shine” from the 1932 film, “Rhapsody in Black and Blue” that frames Marsalis’s comments. Yet that’s not the main point, and there’s little in the way of musical analysis. One could argue—many have—that, say, Armstrong’s opening trumpet cadenzas on his 1928 recording of “West End Blues” is a thorough autobiography in roughly 15 seconds. Here, we don’t learn that Armstrong’s phrasing as a vocalist set the cadence for Billie Holiday, Bing Crosby, and on when it comes to singing past, say, 1930. “Some might say there’s not enough musicology in the film,” Jenkins, a music journalist for many years, told me. “Yet I think before you can understand the music, you have to understand the man.”

As a teenager, Jenkins founded a ’zine devoted to graffiti art. Here, he draws on the visual aesthetic of Armstrong’s homemade covers for his mixtapes. Words (curses included), drawn from interviews and correspondence, move across the screen like cut-and-paste elements; in some ways, the entire film is like a collage, meant less to flesh out biographical details than to explore conflicting feelings and pervasive tensions. At the start, the bell of Armstrong’s trumpet obscures his face entirely. Then we see him, eyes closed, playing his horn. Next, his face, eyes moist, wide open, his mouth caught between a smile and a grimace as he sings “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue.”

With the force of a good cinematic close-up, Jenkins homes in on how Armstrong embodied, expressed and, more often than not in performances, rose above the challenging dualities of being a Black American. This conflicted condition comes across in especially revealing ways through Armstrong’s private recordings. Armstrong shares the pride he took, regularly at concerts, in playing the “Star-Spangled Banner,” which he first learned at the Colored Waif’s Home for Boys in New Orleans —“proud as anyone who ever picked up a gun, shouldered a rifle, and said ‘forward march.’” Yet he was no flag-waver. “I don’t have no fuckin’ flag other than a black flag,” he told friends in hotel room while on tour in 1952.

The N-word comes up again and again, with all its attendant complications: He tells TV host Dick Cavett about a promoter calling him that while refusing to introduce him before a 1931 performance in his hometown; he shares advice he received, before heading north to Chicago, to “make sure when you get up there that there’s a white man that says, ‘You’re my N*****’”; he fights the urge to break a bottle over the head of his then-manager, Johnny Collins, who calls him such, while on an ocean liner together, sailing toward a triumphant 1932 British tour.

In a riveting excerpt of a 1981 episode of the PBS series With Ossie and Ruby, actor Ossie Davis traces his own path to revelation about Armstrong. He recalls laughing with derision at Armstrong (“sweat poppin’, eyes buggin’, mouth wide open, grinning oh my Lord from ear to ear… doin’ his thing for the white man…”). Until he caught Armstrong in a quiet moment, between scenes on the set of the 1966 film A Man Called Adam, “staring up and out into space with the saddest, most heartbreaking expression I’d ever seen on a man’s face. What I saw in that look shook me. It was my father, my uncle, myself, down through the generations, doing exactly what all of us had to do.” In that moment, Davis understood something about both survival and transcendence, and Armstrong’s approach to both. “Beneath that gravel voice and that shuffle…” he said, “was a horn that could kill a man. That horn was where Louis had kept his manhood hid all those years—enough for him, enough for all of us.”

When Jenkins was just 5 or 6, before he knew anything about Armstrong, he was transfixed, he told me, by Philippe Halsman’s photo of the trumpeter for a 1966 cover of Life magazine. “He was playing and looking directly into the camera as if talking to you with his instrument,” Jenkins recalled for me. “There was something about the look in his eye and the strength of his gaze that made me feel something. I didn’t know what it was.”

Jenkins is not the first to cast Armstrong’s legacy in a new light. (Writers Gary Giddins and Dan Morgenstern—the latter a voice in this film—did so notably, decades ago.) But his telling of the trumpeter’s tale is distinct for the force and nuance with which Jenkins recasts the trumpeter’s relationship to social justice and Black American identity. “I don’t know that a white director would have gone down the same rabbit hole I did in the way that I did because, first of all, I don't know that white people are thinking about it in those terms,” Jenkins said. “I don't know if it’s really their place to think about it in those terms.”

His bold and affecting film celebrates both a towering artist of broad, deep, and lasting influence and, as one of his Queens neighbors puts it in the film after Armstrong’s death, “a regular,” just like anyone else. Through this artful view of Armstrong, Jenkins examined not only his subject but himself. He aimed not for a definitive tale but rather a continuing conversation.