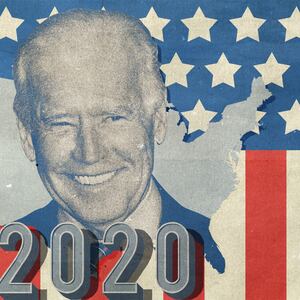

Ever since Donald Trump secured the presidency in 2016, there have been those who have argued that Joe Biden is the Democrats’ only chance at victory in 2020. Why? He plays well with working- and middle-class voters who might otherwise vote for Trump. While many question the merits of this assessment, it appears that at least one important figure has embraced this interpretation: “Middle Class Joe” Biden (his nickname, he assures us).

It is, therefore, puzzling that Biden is seemingly already betraying his supposed working-class base by cozying up to financial industry titans like Blackrock CEO Larry Fink. In January, The Atlantic reported, Biden went to see Fink, who told the ex-vice president "I'm here to help," which Biden took as a sign that Fink wanted a role in his campaign assuming he runs.

Ingratiating oneself to Wall Street executives hardly seems a winning strategy, no matter your base or “lane.” A 2017 poll, for example, found that 72 percent of Americans believe that Wall Street has too much influence in Washington.

BlackRock undoubtedly exerts enormous influence in Washington. Like other corporate giants, BlackRock uses its deep well of resources to buy influence. Since 2004, BlackRock has spent just shy of $22 million on direct lobbying. This level of spending puts it on par with peers in the financial services industry. Additionally, in every election cycle since 2010, the firm has given hundreds of thousands of dollars to campaign committees and super PACs. This is also consistent with peers’ behavior.

It is BlackRock’s use of the revolving door to exert influence, however, that really sets it apart. According to the Campaign for Accountability’s BlackRock Transparency Project, there are 99 people who have moved from BlackRock into government positions and vice versa, including six former BlackRock employees who work at the Securities and Exchange Commission. In 2016, journalist David Dayen catalogued the “veritable shadow government full of former Treasury Department officials” Fink had assembled within his financial empire.

In a pre-election 2016 effort to frustrate Fink’s plans for influence over future officeholders, Elizabeth Warren called out BlackRock as one of three companies from which she did not want to see appointees in a potential Clinton administration.

The threat of BlackRock nominees was real. Larry Fink has long held not-so-secret ambitions of becoming Treasury Secretary. In 2011, when Timothy Geithner’s term was set to expire, he reportedly lobbied Washington insiders for the job. His name appeared on a list of possible candidates but ultimately went nowhere.

Fink’s ambitions, however, did not die, and he began to lay the groundwork for a future shot at the role. In 2014, he hired Cheryl Mills, Clinton’s chief of staff at the State Department and one of her closest advisers, to join BlackRock’s board. He also pulled together a “ready-made team” of BlackRock officials who could move with him to the Treasury Department.

Then Hillary lost, making all of these preparations useless. Or were they?

While Fink was not appointed as Treasury Secretary, he agreed to join President Trump’s economic advisory board (a body that dissolved after Charlottesville), gaining at least some level of additional influence. More importantly, former BlackRock Managing Director Craig Phillips became counselor to Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin despite being a Hillary Clinton “superfan.”

Since Trump has failed to nominate anyone to the Senate-confirmed position of Under Secretary for Domestic Finance , Phillips is essentially filling that role. In that capacity, he has been leading the department’s effort to roll back financial regulations as well as leading its development of housing policy.

And now that Biden is polling well for 2020, BlackRock is hiring a fresh batch of influential, well-liked Obama-Biden alumni. For instance, former Obama National Security Adviser Thomas Donilon is now Chairman of the BlackRock Investment Institute—and beyond having worked closely with Biden in government, Donilon is long-time Biden adviser Mike Donilon’s brother.

Similarly, well-regarded former senior Obama staffers Brian Deese and Wally Adeyemo have also joined the BlackRock team, which feels suspiciously like another government in waiting..

Far from being an exception, BlackRock embodies Americans’ suspicions that corporations control politics, regardless of the party in power. Some companies may brand themselves as relatively benevolent, but their ultimate loyalty is to maintaining political influence in order to maintain and expand profits.

So what has BlackRock used this tremendous influence to achieve? Examples include successfully pressuring federal regulators not to brand it “too big to fail” and lobbying against a rule that would have required brokers to act in their clients’ best interest.

The Clinton campaign’s proximity to BlackRock and other financial institutions may have contributed to its decision to resist identifying entities that were using their power to generate policy outcomes bad for the 99%. Instead, the Clinton campaign emphasized “unity” and “feelgood” capitalism.

Unfortunately, whatever your opinion of this approach’s merits, it is demonstrably bad politics. Indeed, in case you needed another reason to scoff at Howard Schultz’s presidential prospects, he has stated that the “big idea” driving his failing campaign is to “unite the country.”

Resentment toward the wealthy and banks is widespread; indeed, it may actually be one of the most unifying sentiments in American politics. This resentment drives support for policies that until recently might have been considered radical. For instance, 61 percent of voters support Elizabeth Warren’s wealth tax, including 50 percent of Republicans.

Hillary Clinton, for all of her political experience, failed to effectively read the American electorate. Her relationships with people like Fink likely did not help. Which bears the question: why, with the benefit of hindsight, is Joe Biden choosing to emulate her lackluster example?

Biden claims to be staking out the political center. Yet his decision to align himself with the financial sector from the outset of a potential campaign puts him out of step with the vast majority of Americans who want to reduce the power of special interests in Washington.

If by some miracle politically costly alliances with these special interests do not torpedo his campaign, they would likely put his governing agenda out of step with the average American’s interests. Think of a policy that is popular right now. How about the Green New Deal? What would a BlackRock-dominated Treasury Department make of such a proposal? Just look to their example in business. While BlackRock has officially stated its commitment to combating climate change, last year it quietly made investments in the coal industry. What about expanding Social Security (which 72 percent of Americans support according to a 2016 poll)? Larry Fink has publicly advocated privatizing Social Security.

In other words, if given a role in Biden’s campaign and in his administration, people from BlackRock would likely work to rein in his proposals and limit the scope of policy accomplishments once in power.

If Biden truly hopes to reach the presidency by winning the political center, he should take a closer look at the realities of the American electorate by seeking counsel from actual middle-class Americans.