Hurrying to drop off her rent check near her home in Jackson, Mississippi, Jasmine Roberson took a deep breath and did the math: She was seven days late, which took an extra $70 out of her already empty bank account. She has a looming $500 car payment, three boys to feed, a gas tank to fill, utilities. And she has to cover all of this and more with a week less of wages in her pocket, all because a lack of drinking water forced her to make a choice: caring for her children after schools and daycares closed, or going to work.

“I really had no choice,” Roberson, a 29-year-old single mother, said. “It was either my kids having nowhere to go or going to my job, and I chose my kids. It was a stressful moment that put me behind and now I am trying to hold on.”

To make matters worse, she can no longer get help paying for rent. Last month, Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves announced that he was ending the state’s participation in a federal pandemic rental assistance program—which he called a “cruel” “socialist experiment”—and sending back about $130 million in aid funds. About two weeks later, Jackson’s 150,000 residents, 83 percent of whom are Black, were hit with another water crisis that made daily life a lot more difficult and expensive to get through.

For the past six weeks, most of the capital city has been without safe, reliable drinking water after floods knocked out Jackson’s already dilapidated water treatment plant. Thousands of residents in the southwest had absolutely zero liquid in their pipes for more than a week, and nearly everyone is still under a boil-water advisory. Even though the system is back up and running, and federal and state officials have been working on the decaying infrastructure, thick, smelly, brown water is still spurting out of people’s faucets and bubbling up in their lawns. Lead warnings are posted on their bills, which they still have to pay, on top of added costs from not being able to bathe, cook, or operate their businesses.

Without water, public schools and daycares had to close, so Roberson, who is the sole provider of her family, and other parents had to shell out money for food, hotels, and babysitters, or choose to miss work because they couldn’t afford child care. They had to buy bottled water, pay for the extra gas it took to drive around to stores looking for it. Those expenses make or break their ability to pay their rent.

Mississippi has the highest poverty and child poverty rates in the U.S. And like many of Jackson’s residents , Roberson barely scrapes by every month, even though she is working 40 hours a week. When her city experienced its second massive water crisis in about a year, the ripple effects have sent her and many others into a financial hole that feels impossible to escape from.

Residents and social justice experts say state leaders have made it nearly impossible to find support. Mississippi’s governor and legislature have repeatedly dismissed the city’s requests for money to upgrade its water systems. Reeves has cut state programs to help needy residents, the majority of whom are people of color. That’s a big problem for a state ranked as one of the worst in the country for preparing its communities for the climate change fallout.

“We have to talk about the thousand paper cuts that got us here,” Aisha Nyandoro, CEO of Springboard to Opportunities, which helps families in affordable housing, told the Daily Beast. “It’s all interconnected. When you are disinvesting in people you are simultaneously disinvesting in infrastructure and the systems and structures needed to stay and support cities.”

On Aug. 15, under the direction of Reeves, the state stopped accepting applications for federal rent aid related to the pandemic (Three days later, the Justice Department announced that a Mississippi woman tried to defraud the program with fake applications). Reeves was also one of the first governors to opt out of federal COVID-19 unemployment benefits in May 2021. These decisions came at a time when living and housing expenses were at historic highs, Mississippi’s minimum wage was still $7.25 an hour, and many families were still feeling the fallout from the pandemic.

Residents who haven’t had clean and stable water for weeks rely on donations from volunteers who hand out bottled water.

Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Courtesy of Mississippi Black Women’s RoundtableThe state is also in the thick of a massive, historic welfare scandal, in which top officials used $77 million in Temporary Assistance For Needy Families Funds (TANF) to fund projects like sports stadiums and pay big-time athletes like NFL icon Brett Favre. Meanwhile, only 1,681 families received these funds last year, even though about 20 percent of the state lives below the poverty line. Mississippi Today reported that the state denies 90 percent of those who apply, and data from Mississippi’s Department of Human Services show that the number of recipients has been steadily declining since 2018.

Losing millions in rental assistance funds right now is a massive problem and yet another example of the government taking away “an important tool that helps a significant amount of people,” John Jopling, housing law director for the Mississippi Center for Justice, told the Daily Beast. Forty percent of people who are low to moderate-income renters in Mississippi are “unstably housed,” meaning they don’t know whether they’ll be able to pay rent from one month to the next. For those who work to prevent homelessness, Jopling says, layering on the water disaster has laid bare the “full impact of the decision to shut down the rental assistance program.”

“When there is any external event that creates even the slightest increase in pressure in those household budgets, it’s likely to push some people from being unsure to being unable to pay their rent,” he said.

Jackson’s precarious water system has been a way of life for decades. Many residents like Roberson who were born and raised in the city can’t remember ever having clean, consistent water. And while the issue is complicated, difficult, and costs about $1 billion to fix, experts and advocacy groups say it’s largely the result of racist zoning policies, decades of white flight (which has led to a smaller taxbase) disinvestment, politics, and the failures of federal, state, and local leaders to properly allocate resources and account for how they’re being used. The EPA has been involved in Jackson’s water crisis for years, and its top official told NPR that they “were aware that this was a fragile water utility.” The agency’s inspector general is now investigating the emergency.

The latest debacle again exposed the frustrating finger-pointing and friction between the state’s Republican leaders and Jackson’s Democratic mayor, Chokwe Antar Lumumba, who has also come under fire for not attacking the problem. They’ve argued over privatizing Jackson’s water system, with the mayor having accused state Republicans of using it as another tool to take money and control away from his city. At a town hall Monday, he told residents that private companies don't take over a system because “they want to come help. They’re trying to extract a profit from it,” and already struggling customers could be with higher water bills . Lumumba reiterated that he never heard back from state leaders after submitting upgrade plans. However, he and Reeves—whose office did not respond to requests for comment—have also appeared in public saying they are united in helping residents.

Meanwhile, it's Jackson’s residents who shoulder costs they can ill afford. And they are far from alone. Aging infrastructure, lead-flecked pipes, and the inability to access a basic human right plague communities of color across the U.S., most infamously in Flint, Michigan, but also in other parts of the midwest, Texas, and across the South.

Mississippi is getting $4.4 billion over the next five years from President Biden’s massive infrastructure package, but is using $3.3 billion of it to fix roads and bridges and just $429 million to improve water lines in pipes, and it’s still not clear which communities will get the money and how much. The state has also spent resources moving departments outside the capital, like constructing a brand new Department of Public Safety headquarters, which is currently in Jackson, in neighboring Rankin County.

Meanwhile, Roberson says her city is flailing. Water constantly runs in the streets and down her driveway. Her garbage man skips days and her kids’ school buildings are dilapidated. But those are minor problems for her and other Black mothers in Mississippi. They’re primarily the breadwinners, but many of them have low-wage jobs in a state that does not guarantee family or sick leave. House Republicans recently shot down a bill that would have enabled them to have medicaid coverage for a year after giving birth. Right now they have two months. Before Reeves ended the rental assistance program, the majority of its applicants were Black females, Mississippi Today reported.

Mississippi residents gathered in Yazoo City on Aug. 28, 2021 to fill out RAMP applications.

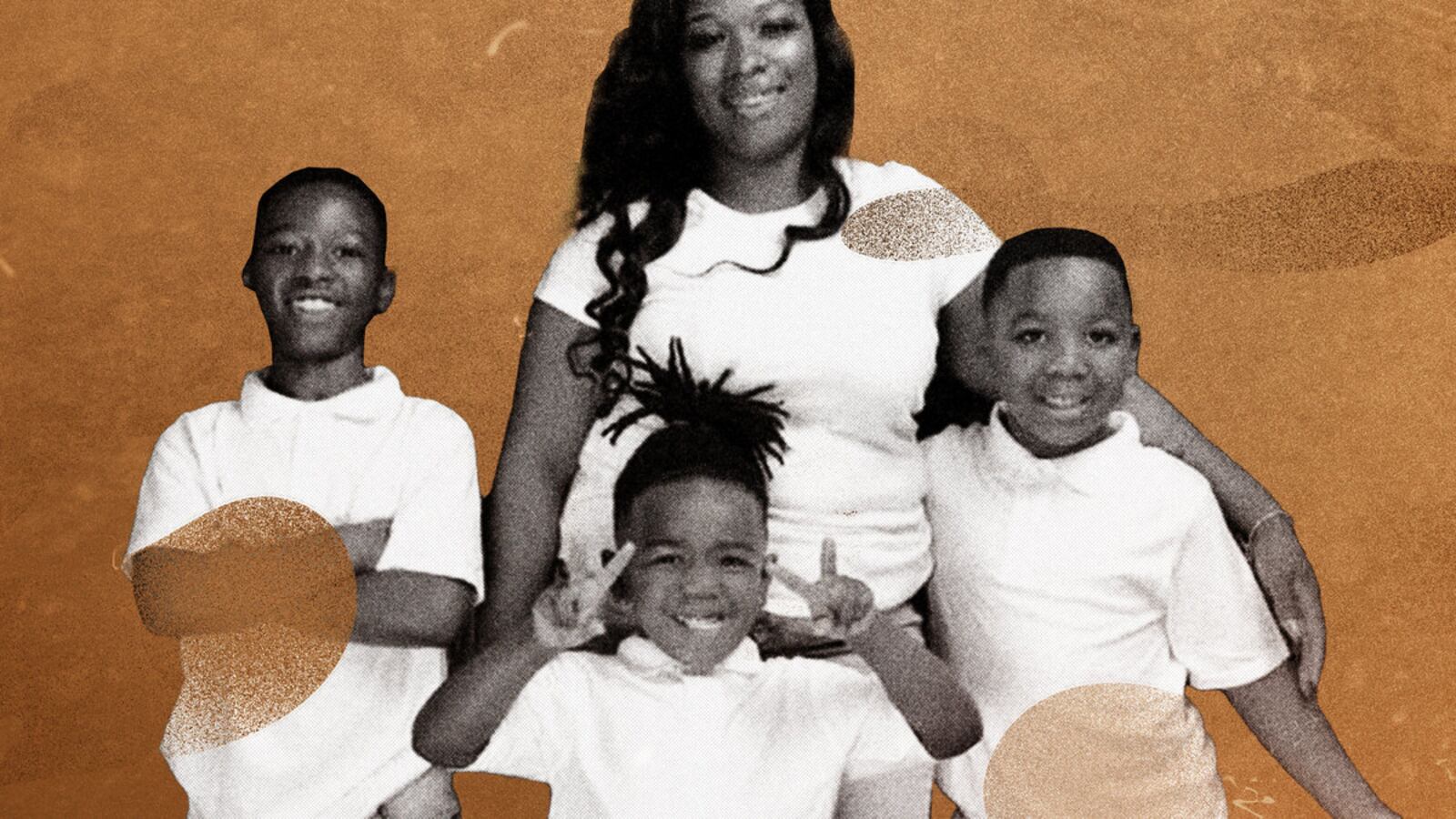

Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Courtesy of Paheadra Robinson/Southern Rural Black Women’s InitiativeRoberson is a medical assistant at a local clinic, where she makes $14 an hour. Her family lives in Atlanta, meaning she juggles her 11-year-old, 5-year-old, and 8-year-old, who was recently diagnosed with a mental disorder, by herself.

“It’s just me,” she said. “I was already going through stuff and [the water crisis] really took me out.”

When Jackson first lost water, she and other families had to use extra gas driving around to stores looking for cases. She found some in Pearl, a predominantly white, more affluent community “whose water is just fine,” she said. Soon, her kids’ public schools closed for a week, and she was really left scrambling. She doled out $200 for a babysitter for two days and then ran out of cash. Left with no real other option, she had to call out of work last-minute. Those five days cost her $336, more than half her rent, and got her in trouble with her employer because she had to call out last-minute, not to mention the extra groceries she had to buy.

The last time she got approved for food stamps or TANF was back in 2011, and she said she has no idea why that stopped. She’s gotten used to stretching and hustling, but her voice wavered when she talked about the moment she learned she no longer could apply for rent assistance.

“Everything’s due at the time when I had no money,” she exhaled. “I’m not even ready for October right now. I’ll cross that bridge when I get there.”

Many other families are also going to be in trouble next month, Paheadra Robinson, a senior policy consultant with the Southern Rural Black Women’s Initiative, told the Daily Beast. Her organization, which helped 500 people with rental assistance applications, is already seeing the consequences for economically challenged families who had to dip into money they set aside for rent and utilities to buy food and water.

Analyzing data from the Mississippi Center for Justice, which runs the only statewide eviction prevention hotline, Jopling agrees. He said a third of their 700 callers got rental assistance that deferred a family’s eviction or prevented it from going forward in court. Now they’re bracing for the double whammy of the water crisis and the termination of the rental assistance.

“We don't know what is going to happen,” he said. “But we know it’s going to be bad.”

With her rent handled for September, Roberson is trying to get the rest of her life back on track. She’s applying for family leave, which is unpaid, in case she misses any more work due to the disaster, getting more bottled water to handle piles of unwashed laundry, and figuring out how to pay for a car repair and two of her sons’ upcoming birthdays. She also still needs to bathe. Like many other mothers, she refuses to wash her and her childrens’ bodies with even boiled water. The liquid spurting from her pipes is brown, “gooey,” and smells like hot soil and rotten eggs. And that water still costs her $40 a month.

It’s all a lot, but she’s used to that. When asked what would make her life a little better, though, she quickly replied with one thing:

“I would love a hot bubble bath right now,” she answered. “I can’t remember the last time I’ve had one.”