According to the old rules of American politics, Mitt Romney should win the Republican presidential nomination. He came in second last time. He’s got lots of money. He’s got a better chance of defeating Barack Obama than his leading opponents. But he’s unlikely to win because we live in an age of presidential hatred. These days, to win your party’s nomination you must be the polar opposite of the president your party despises. Any significant resemblance between yourself and him and you’re done.

Successful challengers have always drawn contrasts with incumbents, of course. But there was a time, not long ago, when some ideological overlap with a president from the other party was actually an asset. In 1992, Bill Clinton did not run as the polar opposite of Ronald Reagan. To the contrary, he beat more liberal contenders like Tom Harkin in part by arguing that his more moderate positions on welfare, taxes, and the death penalty would help him win over Reagan voters. In 2000, George W. Bush defined himself as a “compassionate conservative” in order to woo voters who had appreciated Clinton’s ability to “feel their pain.”

The turning point, in retrospect, was 2004, when all the early frontrunners for the Democratic nomination—John Kerry, John Edwards, Richard Gephardt, Joe Lieberman—supported the Iraq War in an effort to narrow the differences between themselves and President Bush on national security. Liberal primary voters responded by embracing Howard Dean, who by opposing the Iraq War cast himself as Bush’s polar opposite. Dean’s campaign collapsed, but through institutions like MoveOn, Daily Kos, and MSNBC, his militant ethos took over the Democratic Party.

As a result, when Hillary Clinton ran in 2008, her inability to draw clear distinctions with George W. Bush—especially on the Iraq War, which she too had supported—alienated her from the Democratic grassroots. Animated by their hatred of George W. Bush, Democratic primary voters yearned for his opposite. And it was Obama, who had opposed the war and was not implicated in the old Democratic strategy of blurring differences with the GOP, who became that man.

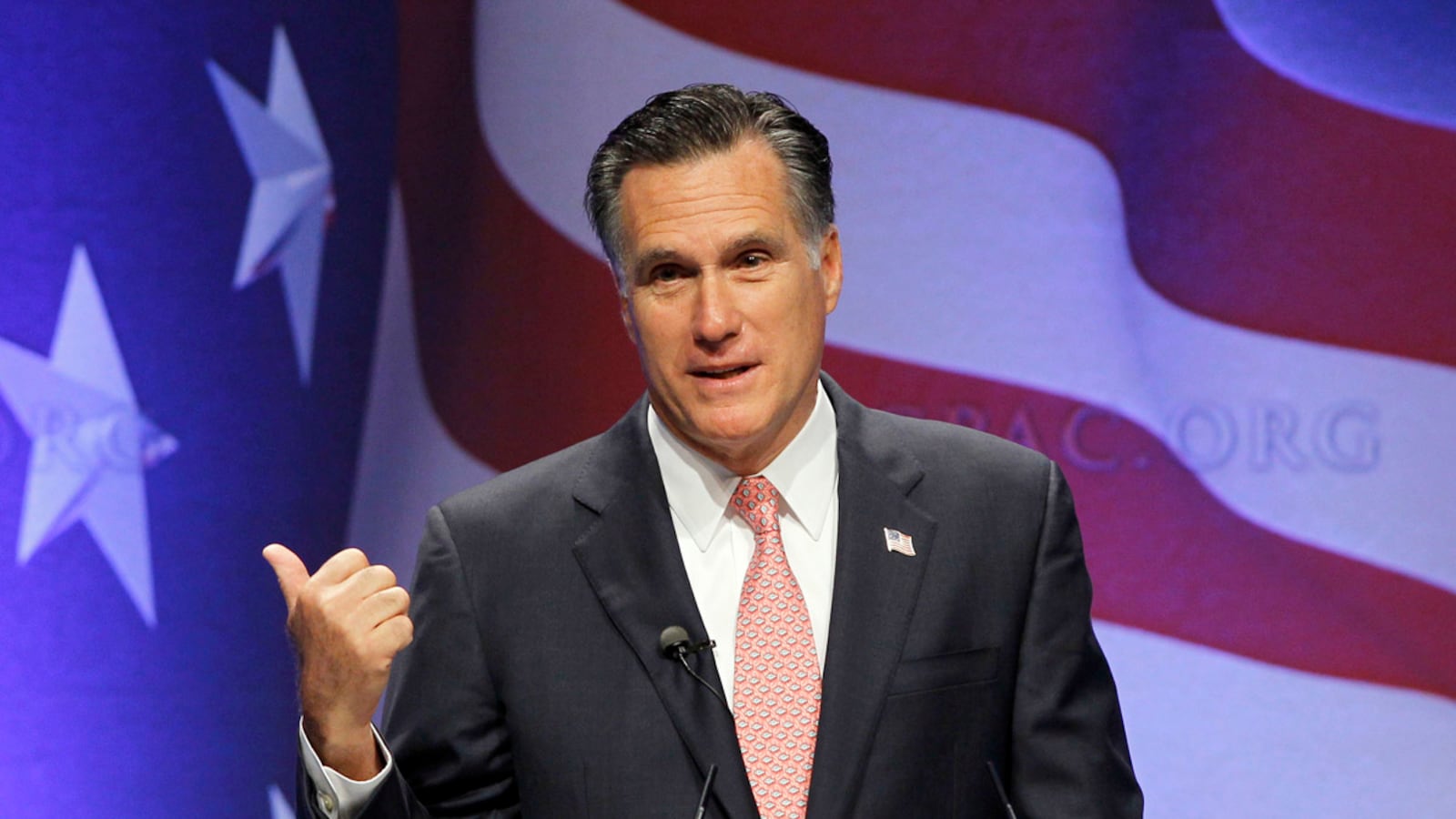

Mitt Romney is this cycle’s Hillary Clinton because health care is this cycle’s Iraq. Like Clinton, Romney is competent and polished and has a powerful political machine. But his inability to draw a sharp contrast with a hated president on the issue that makes his party hate that president most is sucking the passion from his campaign.

As Politico recently noted, even Republicans who support Romney support him less intensely than those who support Michele Bachmann and Rick Perry. Almost overnight, Perry has leapfrogged Romney for the lead in national polls, even though substantially fewer Republicans know who he is. Perhaps most ominous is Romney’s testy relationship with the Tea Party, the movement that has taken over the Republican grassroots in the same way the anti–Iraq War movement took over the Democratic grassroots during the Bush years. When Romney went to speak in New Hampshire this week, a group of Tea Party activists showed up to protest.

It’s always possible that Romney could win the Republican nomination the same way Kerry won the Democratic nomination: because the candidate who inspires more passion implodes. But while Bachmann bears some resemblance to Dean, Perry does not. He was governor of a much larger state, he’s got a much more professional campaign, and he’s unlikely to run out of money. If Perry wins Iowa, where he’s already leading in the polls, Bachmann and all the other right-wing candidates will likely become afterthoughts. Romney will make his stand in New Hampshire, which has a more moderate electorate. But as Nate Silver of FiveThirtyEight has pointed out, while Romney leads each individual conservative challenger in the Granite State, if you total up their support, it significantly exceeds his.

Thus, if Sarah Palin doesn’t run, and Bachmann, Newt Gingrich, and Herman Cain become irrelevant, Perry’s support in New Hampshire could grow fast. After New Hampshire, the race moves to South Carolina, where political ideology, cultural affinity, and religious bigotry all cut Perry’s way.

When they look back at the 2012 Republican presidential contest, pundits may well conclude that Romney, like Hillary Clinton in 2008, was too clever by half. Thinking that Republicans wanted a candidate who could appeal to Democrats, Romney took a series of centrist and even liberal positions that helped him become governor of a blue state. Now those positions are coming back to haunt him as Republican activists demand a candidate of unbending right-wing convictions. Whether the American people actually share those convictions doesn’t particularly matter. What matters is that they are not shared by the president of the United States.