You don’t have to be a member of the media to go read Hillary Diane Rodham’s senior thesis. You just have to get yourself up to Wellesley and do it in person. And I should warn you that the cab from Logan ran me $75, without tip.

They get a lot of calls about it, the nice people at Wellesley told me, but when the callers are informed that they have to come read it in person, few follow through. I assume that most of the callers are Hillary haters, on the prowl for evidence of her plot to destroy America

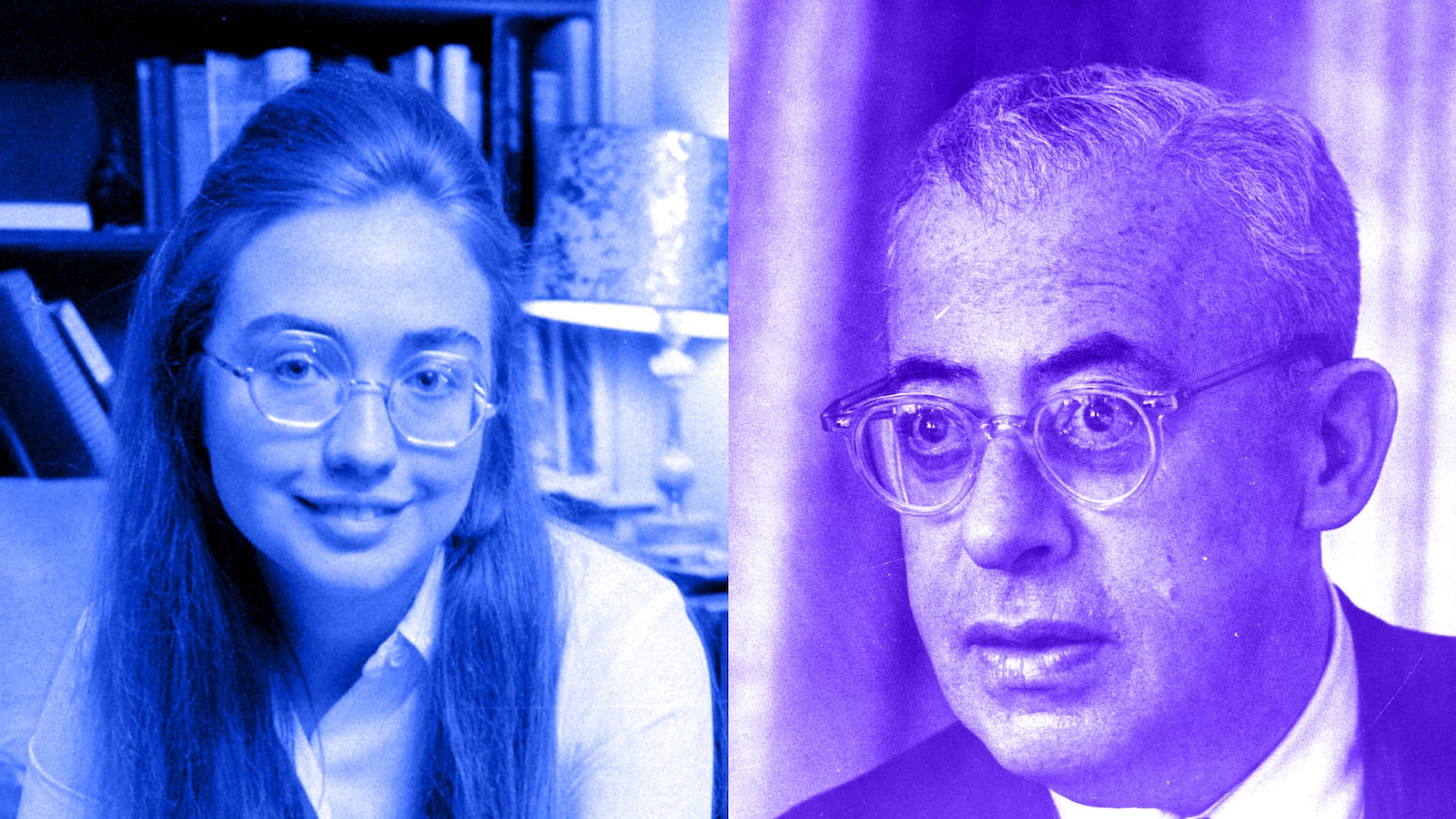

Spoiler alert: If you go there searching for sentences like “Comrade Alinsky has shown us the one true way to overthrow the existing order,” you will come away disappointed. The Hillary who comes across in the thesis’ 74 pages is basically the Hillary we know, albeit a slightly farther left, college-age version. And like the Hillary we know now, the young woman who wrote this paper is hesitant to reveal much about herself, except in one striking sentence at the end, which we’ll get to.

It was fascinating just to see it, in a way. Christopher Hennessy of media relations walked me up to the archives room and introduced me to Mary Yearl, who was behind the desk; she pointed to a slim, hard- bound manuscript cradled on two foam wedges atop a conference table. “There it is,” she said.

If you’re young, you’re wondering what I’m banging on about. But if you’re of a certain age or are a true Clinton-scandal connoisseur, you know that back in the 1990s, this little document was purported to contain all the clues needed to crack the case of Clinton’s well-concealed radicalism.

Why indeed did she even choose as her subject Saul Alinsky, the organizer of poor people’s campaigns who proudly proclaimed himself a radical? I seem also to remember some craziness about how she’d had every copy burned or something. The thesis, in the right-wing fever swamps, was the Red Rosetta Stone. (This is the conspiracy theory Ben Carson revived, with quite a twist, at the Republican Convention, when he veered off script to tie Clinton, through Alinsky, to Lucifer.)

So what is it actually? It’s called “There Is Only One Fight: An Analysis of the Alinsky Model.” The title comes from an Eliot poem that serves as the epigram. There’s a short, cheeky Acknowledgments paragraph (“Although I have no ‘loving wife’ to thank for keeping the children away while I wrote...”), and a specific date, rendered as “2 May, 1969,” three weeks after 300 Harvard students seized the administration building, which our coed would surely have been watching closely.

Basically, Clinton seems to have been interested in two questions, one concrete and one abstract. The concrete one was: Can poor people be organized into a powerful political force? The abstract one, which was in the water on college campuses in those days, could be put something like: What do these words like “radical” and “democracy” even mean, and can we challenge their currently understood meanings in ways that might distribute power more broadly to those who don’t have it? Here’s a short but representative passage:

This faith in democracy and in the people’s ability to “make it” is peculiarly American and many might doubt its radicalness. Yet, Alinsky’s belief and devotion is radical; democracy is still a radical idea in a world where we often confuse images with realities, words with actions.

Her musings on the abstract question go back and forth between endorsing a more confrontational posture here and one more rooted in consensus there. There’s a long discussion of conflict theory, which was pretty au courant at the time, and which held that conflicts between groups that have unequal power are inevitable and necessary and can provide the necessary group cohesion to spur the less powerful group to action. Put more simply, that conflict can serve a social function. She cites the sociologist Lewis Coser a lot, who strikes me as a very Hillary sort of person to cite—he was of the left but also a critic of the left.

The longest chapter looks at three case studies of Alinsky organizing projects and why they succeeded (in the first case) and failed (in the other two). The first case was the Back of the Yards neighborhood of Chicago, where Alinsky’s efforts were successful in bringing jobs and opportunity to the neighborhood in part because the people there were white ethnic Catholics who had real representation in City Hall, including in the form of Mayor Richard J. Daley himself. The two other cases, in Chicago’s Woodlawn neighborhood and in Rochester, New York, didn’t work out so well; the reason, of course, was race. In Rochester, Alinsky formed a group in the black neighborhood called FIGHT. The Kodak Corporation at first was actually cooperative, even promising to build a plant there, which it never did, at least as of May 1969.

The Woodlawn effort collapsed after the group Alinsky formed got a $900,000 War on Poverty grant, some of which went to gang leaders who were persuaded to take on organizing roles. These payments were derided as “bribes to gangs” (black, needless to say) and led to congressional hearings and an investigation. Clinton writes: There is about [the Woodlawn] fiasco…an incredible naïveté. Nathan Glazer has explained it saying that it is as if “someone had been convinced by a sociologist that change and reform are spurred by conflict and decided that, since all good things can come from the American government, it ought to provide conflict, too.”

There’s a fair amount of anti-government rhetoric in the paper—criticism of the War on Poverty, notably. This might seem surprising at first blush, but if you understand Alinskyism, it makes perfect sense, because Alinsky was all about local control. He was very suspicious of the feds butting in, and Clinton imbibed some of that from him.

This section of the paper also includes a short critique of Daniel Patrick Moynihan—interesting in light of the fact that three decades later, Moynihan would welcome her to New York and she would win his Senate seat. Clinton thought that Moynihan, a Harvard scholar and Nixon adviser then, was naive about the willingness of Congress to fund initiatives for the poor. But she does conclude her discussion of the War on Poverty by quoting old Pat approvingly:

All too often the War on Poverty with confused intentions and armed with misinterpreted social theory fulfilled Moynihan’s concluding description of the community action programs: “…the soaring rhetoric, the minimum performance; the feigned constancy, the private betrayal; in the end…the sell-out.”

So what do we learn from all this? We learn some things about what she thought then. I’m not sure to what extent we can ascribe these things to her all these years later. She found much to admire in Alinsky, who sat down for two interviews with her and showed her around his Chicago. Here’s the paper’s concluding paragraph:

If the ideals Alinsky espouses were actualized, the result would be social revolution. Ironically, this is not a disjunctive projection if considered in the tradition of Western democratic theory. If the first chapter it was pointed out that Alinsky is regarded by many as the proponent of a dangerous socio/political philosophy. As such, he has been feared—just as Eugene Debs or Walt Whitman or Martin Luther King has been feared, because each embrace the most radical of political faiths—democracy.

But her admiration went only so far, which brings us to the project’s sole genuinely revealing sentence. It doesn’t appear in the body of the paper, but under Primary Sources, where she describes how generous Alinsky was with his time and even then offered her a job. She writes: “His offer of a place in the new Institute was tempting but after spending a year trying to make sense out of his inconsistency, I need three years of legal rigor.”

The barricades weren’t for her. If there’s some plan to bring down America in these pages, it was, and has remained, very well concealed.