RICHMOND, VA -- One floor below the Virginia State Senate chamber, Wilktion Shaw works as a cook at Meriwether’s. It’s a cafe well known to those who come to the state Capitol, cooking up soup, sandwiches and salads and serving everyone from teenage pages to elected officials in need of a quick bite.

On normal days, a steady stream of customers will come through its doors. But these aren’t normal days.

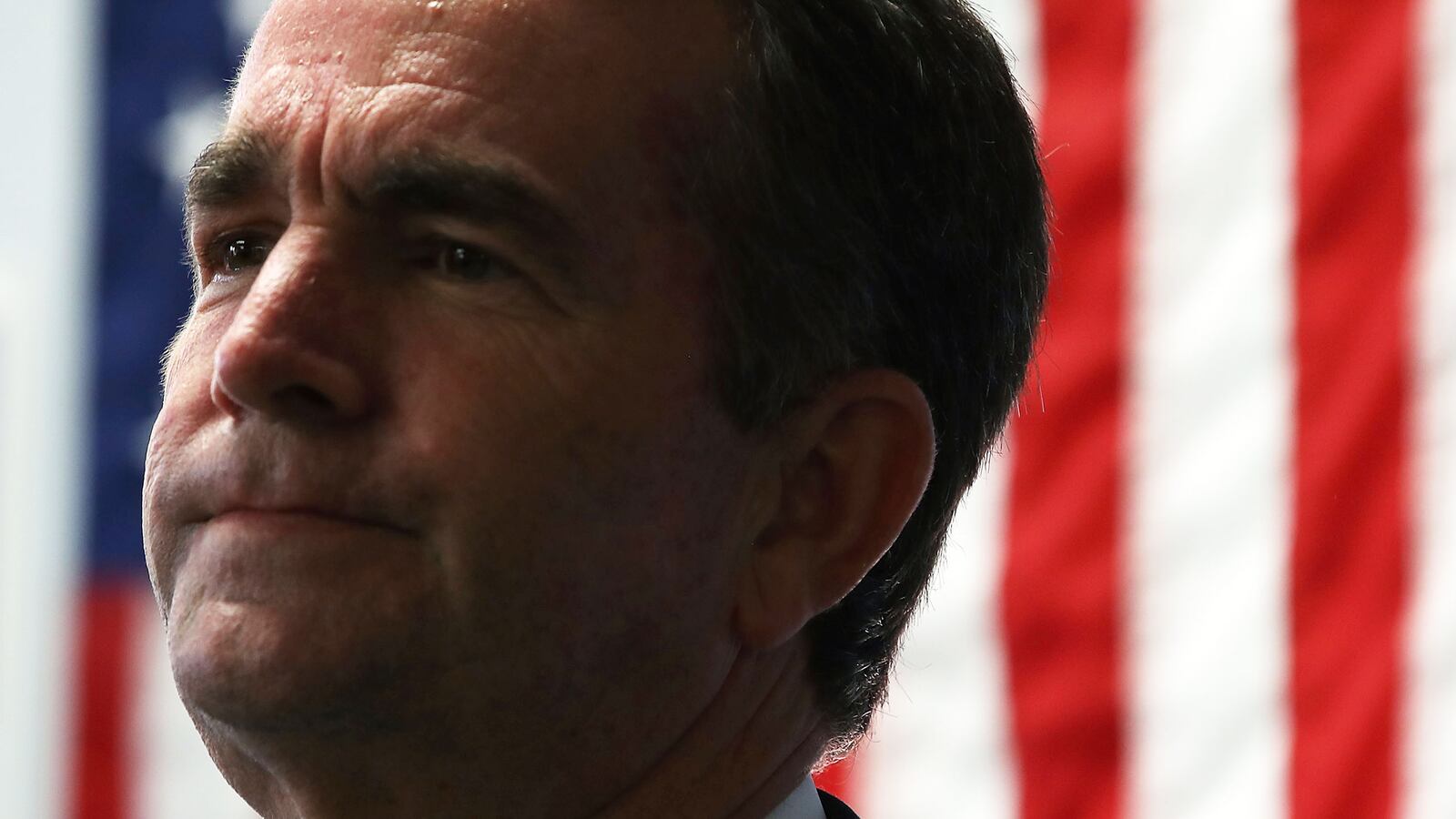

Virginia politics has been swamped by a tidal wave of scandal since the state’s governor and attorney general both admitted to wearing blackface decades ago, and the lieutenant governor was accused of sexual assault. In response, the national media has descended upon Richmond, opening up cultural wounds across a state with an already checkered history on matters of race.

For Shaw, who is in his sixties, it’s made business “quite busy.” But beyond that, not much of a shock has been delivered to the system. A black man who has lived in Virginia for more than 17 years, he says he isn’t surprised by the current drama.

“Things like this always happen,” he says. “There’s just a light shining on it now.”

Cooking professionally was a fairly recent career change for Shaw. He trained as a clinical social worker, and was employed for decades at Virginia’s child and adult protective services hotline, overseeing a staff of 22. This is his first General Assembly session at the cafe.

Attorney General Mark Herring and Governor Ralph Northam, he says, should take responsibility for their actions. But he is OK with their staying in office as they make those amends.

“I think everybody has something in their past,” said Shaw.

Like many statehouses, Virginia politics has been run mostly by white lawmakers with mostly white aides, though the delegations and offices have become notably more diverse over time. The workers who assist those politicians and their staffs—the ones who perform the janitorial services, cook their food, and help secure the buildings—are more diverse than the lawmakers themselves. They came to Richmond not because of some long-standing desire to enter public service or ascend the ranks of electoral politics, but because there was a job that paid.

These past two weeks, they’ve been confronted with harsh proof that the government they serve is run by individuals with dark, racist moments in their past. And many have taken it in their stride, saddened but unsurprised by the revelations.

Anthony Ross works as a janitor at the Capitol. A lifelong Richmonder from the historic Church Hill neighborhood where Patrick Henry made his famous “Give me liberty or give me death” proclamation, he too said he was not shocked that elected officials wore blackface, even as recently as the 1980s.

“They’re just insensitive. I just assume people do that all the time,” says Ross, who is black. “I wasn’t bothered by that in the least.”

In the underground extension of the Capitol, where Ross, 35, spends most of his time at work, he passes a Confederate flag on display as part of a historical exhibit. In January, he went to work on Lee-Jackson Day, when a few state legislators spoke in praise of the Confederate generals as part of the official legislature record. Northam’s scandal, for him, is a feature and not a bug of the state’s political structure.

“I don’t think he’s racist,” he says of the governor. “I just don’t think he has any black friends.”

When a photo in Northam’s 1984 Eastern Virginia Medical School yearbook was made public—showing two men, one wearing blackface and the other in KKK garb—Ross joined the chorus of those who assumed that the governor would resign. But his opinions have since changed. Herring, who had called for Northam to step down, subsequently admitted that he too had worn blackface during his teens. And Ross now says he doesn’t think either official would leave office because of the chaos it would cause.

That Northam has since said he would dedicate his time in office to trying to heal racial wounds, and that his administration expanded Medicaid to about 400,000 more people last year, has weighed positively on Ross.

“He’s done more than people think” to help black Virginians, Ross says.

Not everyone is resigned to Northam staying put, or willing to let him regain their trust. On Wednesday evening, a small group of protesters gathered near the governor’s mansion, within view of monuments honoring Harry F. Byrd Sr., the former Virginia governor and senator who supported segregationist policies, and a bronze cast of Prince Edward County students who walked out of their school to protest “separate but equal” institutions.

Among the protesters was Terron Sims II, an Iraq war veteran, a 2000 graduate of West Point and a member of the group Black Virginia Politicos. At 41, Sims has worked for multiple Democrats’ campaigns, including Hillary Clinton and President Barack Obama, representing Virginia’s veterans and military families. Earlier this year, Northam named him to the Virginia Complete Count Commission to assist the 2020 U.S. Census count. But he had come to Richmond on Wednesday to express his discontent.

“We can’t force the governor to resign,” Sims said. “This is to apply pressure for him to resign. If he were to choose to stay in, we would like him to sit down with black Democratic leaders to construct executive orders he can execute” that would benefit black Virginians.

Sims said he has no comment about Fairfax or Republican State Sen. Tommy Norment, who edited the 1968 Virginia Military Institute yearbook that included blackface photos. But he accepted the apology from Herring, who met with black legislators and others to offer his regrets.

“For us, he’s good,” said Sims. “This protest is solely about our issue with Ralph.”

Mike Brown, a Richmond city councilor who spoke at the protest, said he “loves” Northam and supported him in the past as a fellow Democrat. “I forgive him,” said Brown, “but now I want him to be accountable. We can’t put party over people.”

A member of the Charlottesville City Council, Wes Bellamy, took a blunter approach. He said he considers Northam a friend, too, but the way that the governor has handled the blackface revelation—first admitting he’d been pictured in the yearbook, then denying it but saying he’d donned blackface to impersonate Michael Jackson, before nearly moonwalking during a press conference—had indicated to Bellamy that “he is not qualified in any shape, form or fashion, to tell us how he’ll move this commonwealth forward.”

On the sidelines of the rally stood Altariq Ramadan, who held a copy of W.E.B. Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk, checked out from a local library. A 71-year-old Richmonder, he said he lived through segregation in the city’s Byrd Park neighborhood, where tennis legend Arthur Ashe also grew up. Ramadan recalled being forbidden to swim in Byrd Park’s swimming pool because he was black, as a child in the 1950s, just as Ashe was prevented from playing on its tennis courts. This week, Richmond City Council voted to rename a main boulevard near the park for Ashe.

Ramadan had that history on his mind as he showed up on Wednesday, not to protest Northam but to watch the latest scene of racial strife unfold.

“I think he should reconcile himself. I think he should atone,” but not resign, Ramadan said. “He needs to consult with people of color.”

And that’s precisely what Northam has said he is going to do as he continues serving in office. Next week, the governor plans to attend a discussion at Virginia Union University, founded in 1865 to educate freed black men. Earlier this week, he continued a policy of his predecessor in announcing that he was restoring the voting rights of thousands of convicted felons, in what was widely interpreted as a nod towards burnishing his badly damaged position on matters of civil rights.

As he watched the scene unfold, Ramadan pointed to an area next to the governor’s mansion where slave quarters once stood.

“My family’s roots are former slaves and cooks for Governor [David] Campbell,” he said, in reference to the mid-19th century governor who brought enslaved men and women to Richmond from his home in Abingdon.

Things have changed dramatically since then; and, also, not at all.

“Thomas Jefferson had slaves. Nobody impeached him,” Ramadan says. Today, “all you can do is make it better.”