Feud: Capote vs. the Swans is up to its long, regal neck in catty delights. For a show about an author who was as famous for his biting prose as for his equally acerbic, conversational wit, that pen-sharp venom comes with the territory. Truman Capote made no qualms about his penchant for gossip; his most successful novel, 1966’s In Cold Blood, elevated salacious whispers and local chatter to the gripping status of great true crime. He was a figure beloved for his candor and empirical humor—but that same observational intellect became the cause of his downfall.

Capote’s societal demise is deftly captured in the long-awaited second season of FX’s hit anthology series (now streaming on Hulu), which follows the dissolution of the relationship between the author and his circle of friends: a powerful, ethereal group of high society women he deemed his “Swans.” Actor Tom Hollander, who took on the formidable task of embodying the singular novelist—whose looks and manner of speaking were as notable as his writing—said that the show is a tale of an outsider who finds himself back at square one. “[Capote] ends up as he began,” Hollander told me over Zoom before the show’s premiere. “He’s so wrapped up in the establishment, but he’s rejected by it.”

That rejection happened after the publication of “La Côte Basque, 1965” in Esquire magazine, a chapter from what would become Capote’s final, unfinished novel Answered Prayers. In it, he revealed choice details about the scandalous lives of the Swans, but none more so than his closest friend Babe Palley (played by Naomi Watts in the series). Also struck by the shrapnel were Lee Radziwill (Calista Flockhart), Slim Keith (Diane Lane), and C.Z. Guest (Chloë Sevigny), who launched a very public takedown of the chapter’s author.

Capote vs. the Swans explores this era in vivid, enchanting detail—and gives its ensemble cast plenty of campy material to throw around at sprawling party scenes and intimate dinners. The Daily Beast’s Obsessed spoke to the cast—Hollander, Flockhart, Sevigny, and Lane—about how fun it was to play malicious socialites, why they think the Swans were so scorned after their friend’s betrayal, and the ultimate tragedy of Capote’s downfall.

Naomi Watts, Chloe Sevigny, and Diane Lane

FXThe show begins with all of the cutting campiness that one would expect from a series about Capote and New York society, and then transforms into something much more stirring and introspective as it goes on. How do you balance that difference between emotional resonance and camp? That’s something Capote did so well in his own writing.

Hollander: Yeah, I agree with you about the writing. It’s in the writing [of the show]. Jon Robin Baitz, tonally, he was very wide. He goes to all sorts of places. It’s crazy. They let their creative imagination go anywhere it took them. And the nature of Truman Capote is that it allows you to do that because you can go in and out of fiction, and in and out of biography. It’s about a writer, isn’t it? So you can play with the creative; it’s coming out of a man’s head. So as an actor, you play the episode you’re in. The episodes were like different films, they had their own distinct tones. That made it very exciting to do because you weren’t just doing the same party trick each episode.

I imagine that’s nice when you’re doing something like this, because it seems like a lot of work day in and day out. The level of detail is so precise.

Hollander: Yes, because it’s months! I haven’t thought about this for a long time. It reminds me why it sustained us. It was a hard, long job every day. But the tonal shifts in it were exciting.

Calista, I’m interested in how you feel about jumping between the show’s campier side and its more emotionally evocative one. Lee has so many moments where she twists the knife and then other times she’ll pull back and play a bit more coy.

Flockhart: I think Lee—well at least the way that it was written, I can only imagine what Lee was really like I preface everything I say with that! But Lee was very good at the facade. She was very performative. In the episode where they’re doing the documentary, she’s making sure she’s always on her game, she’s always putting up the facade. She goes home in one scene where she’s no-makeup, her hair is straight, and she’s crying, because at the end of the day, there’s loneliness and sadness.

That’s such an important scene.

Flockhart: She was very dependent on Truman because she was never seen by anybody. She was in the shadow of her sister, Jackie Kennedy. Truman saw her, said she was better, said was more interesting, said she could do whatever she wanted. So she developed this very codependent need for that. But she also did not get killed in [Answered Prayers]. She didn’t get so thrown under the bus. But she had another fight with him about something else so she just put that armor on and that was it.

Sevigny: I think they’re trying to get to the root of why Truman would do this, and I think a lot of that came from writer’s block which maybe stemmed from his alcoholism. He really loved these women and spent so much time with them and knew them so well. What would cause someone to do this? To hurt people that you love? That’s really what the show is about: How could he get to such a point that this was the right choice, to follow through with it?

Lane: It takes so long to grow a relationship and it’s so easy to lose one. He managed to do that and it is a bit of a shock. Especially speaking to Calista’s point before about the brilliance of Truman in seeing what each person in the room would respond to. He could have that X-ray vision about people’s wounds and know what to say to them to bait them to make them feel seen and secure in his company, that he would reassure them. He knows exactly where their Achilles’ heel is, and he’s going to speak something that other people—what do they say, “Say the quiet part out loud?”—he did that.

Yes! Precisely.

Lane: He had a gift for that, which he was restraining at all times. He was just bursting at the seams waiting to be honest with someone about what he was really thinking. So he was just one of the gals! Because we too had to bite our tongues and play nice, and be in society, and be proper all the time.

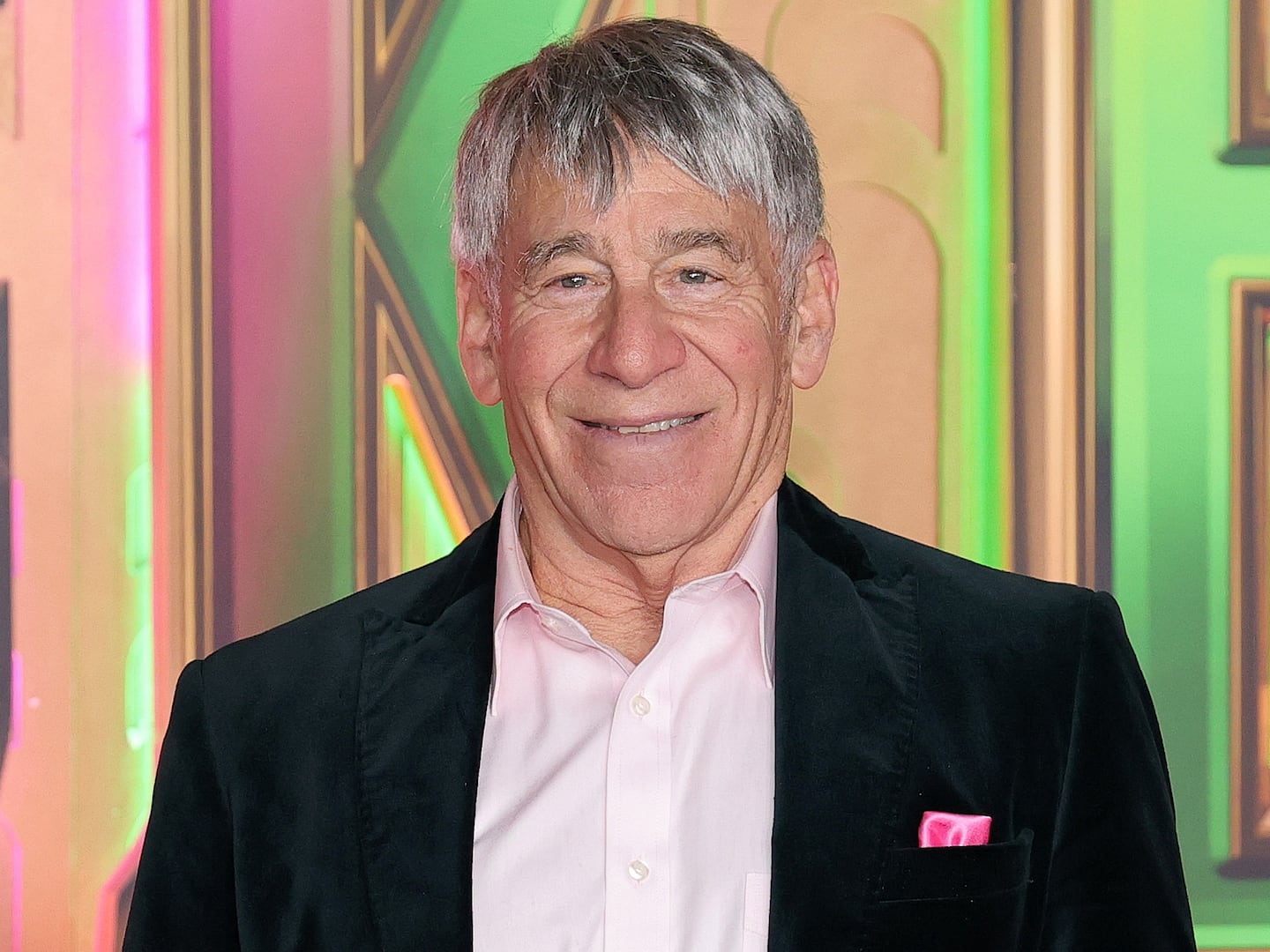

Tom Hollander

FXTom, Truman and Babe’s relationship is the emotional center of the show, and you and Naomi have such an affecting chemistry, particularly in the latter half of the season, as both of your characters’ health is declining. What was it like to traverse that spectrum of friendship alongside her? Babe and Capote eventually separate, but they remain on each other’s minds.

Hollander: Yes, like you miss estranged friends. It all felt very natural, maybe because I’m old enough to have experienced that myself. I have some very old friendships that are not active. I often think about those people, but I don’t see them anymore, so I’m familiar with the feeling. But in terms of the intimacy between us, I would credit Naomi with that because she was so warm and sweet and kind to me from the outset. We both made a conscious effort to make sure that we got to know each other, and we were very fond of each other very quickly. Then it was just a question of expressing that, mucking around, playing. You’re supposed to play. “Now you two, you’re going to be best friends, so you play being best friends!” And then it happens.

This is a love story between Truman and Babe, but given that you’re a theater actor—which I imagine comes with a good grip on the idea of a tragedy—I’m curious, do you see this story as sort of its own American tragedy?

Hollander: Ooh, gosh, that’s a big question. An American tragedy?

It does feel distinctly American in a way that it imagines the uniqueness of New York society in that era.

Hollander: Yes, so it’s site-specific in that sense. It’s also a love letter to that period, isn’t it? To a period that’s gone and a New York that’s gone. We’re all so conscious of how everything is changing so fast and nothing is as it was. Things that we thought were certain are not. There’s a security in those old images of the ’60s and ’70s, even [in] a counterculture figure like Truman. He’s so wrapped up with the establishment but he’s rejected by it, so he ends up the outsider he began as. It’s full of tragedies. In Shakespearean tragedy, it’s often the nature of the person that destroys them, and that is definitely true of Truman Capote. And so in that sense, his life does have a sort of formal tragic arc, because he knew he was destroying himself and he couldn’t stop it.

The show doesn’t shy away from the extent of those demons, either.

Hollander: It’s a story about addiction. The addicts I’ve met in my life… it’s very rare that you meet an addict who doesn’t know they’re an addict, so when they go back to whatever their addiction is it’s fully conscious and that’s why it’s pitiable. It breaks your heart because they know it themselves.

Chloe and Calista, your characters C.Z. and Lee take a little bit more of a shine to Truman after the initial betrayal, more than Slim does. Do you think it was different for them compared to Slim?

Sevigny: In real life, C.Z. and Truman remained friends until he passed. There are photos of them at Studio 64—which I haven’t watched, but I’m assuming it made the cut in the show [laughs]—because Truman hadn’t thrown her under the bus. Even though she was loyal to her girlfriends, Truman gave her something that was lacking in her life. The directors have to have different colors for the Swans during the series and C.Z. became that person that Truman could go to and lean on, and I’m sure in real life it was the same. She saw him as this wounded bird himself. She felt sorry for him and felt sympathy for him. She tried to understand why he had done that. She was more empathetic, perhaps.

Slim, C.Z., and Lee are each so different, despite being a part of the same group. What was it about each of your characters that attracted you to these parts and made you think, “I’ve got to play this person.”

Lane: Well I’ll just pipe in and say it was really refreshing and fun to be a group of women on film together. That doesn’t happen often enough in my opinion, as an audience member or a person in front of the camera. I found it very rewarding as an experience.

Sevigny: Unfortunately, I haven’t had very many opportunities to play glamorous characters. So first and foremost I was like, “Bring on the glamor, the fashion, the hair, the makeup!” I have been obsessed with Truman since I was in high school, when I first learned about him and read about him and his relationships with so many fascinating women, writers, socialites, movie stars, etc. So for me, it was really to be able to play this woman through Truman’s eyes, to a certain extent, and to help tell his story. I thought there was something just very genuine about C.Z. She was really kind of no-nonsense. She was of a certain air but she wasn’t putting on airs. She was very solid in her being. To play a glamorous character like that was kind of fresh.

Calista, your Lee is out of this world. It’s so much fun to watch you inhabit this icy character. What was it like for you to take on this role, something different than what we’ve seen from you in the past?

Flockhart: It was a lot of fun. It was intimidating because I admire Diane, Naomi, and Chloë so much and have done so for a long time. And there’s a whole part of Lee that isn’t in this story. She had this relationship with her sister that really, I think, defined who she was as a human. So you do all that work and then you just get to come on and quip around a little bit.

Diane, there’s this great scene between Lee and Slim in the fourth episode, where Lee tells Slim to lay off Truman, but Slim remains worried that the literary knife could keep cutting at them. It’s haunting that these headstrong women spent so much of their lives consumed by their worry and anger. Having spent time studying these women so closely, why do you think they held onto it for so long?

Lane: As mentioned in [the show’s script], writers get to dictate how things are remembered by the words that they choose, because that’s what’s left for the next generation to harken back to and say, “Well oh, that must be true, that’s what’s written down!” And I can tell you right now that I don’t have a middle name, but the internet gives me one. [Wikipedia lists Lane’s full name as “Diane Colleen Lane.”] So I’m just saying it’s crazy what people will believe just because it’s written down. I think that having your character besmirched was not de rigueur at that time, and certainly not by this population. Those privileged folk, high on the hill, were not going to stand for being remembered that way.