Not 20 minutes into Good Grief, the feature-length directorial debut from Schitt’s Creek star Dan Levy (streaming on Netflix Jan. 5), the actor—who also wrote and stars in the film—tees up the first of several soft-spoken meditations on loss. “I’ve been reading that the brain is like a muscle,” Levy’s character, Marc, says about the recent death of his husband. “That’s why getting over a death is so hard: because your brain has been trained to feel things for a person. And when they go away, your head is still operating under the impression that it should feel those things for that person. Like…muscle memory.”

While that is a completely surface-level and obvious examination of the feeling of grief, Levy delivers the dialogue he wrote for himself with a navel-gazing sense of pride, thinly masked by his character’s monotonous tone. There’s a false profundity to this and the countless other itinerant soliloquies that make up Good Grief. These shallow vignettes—which are practically lab-designed for Netflix to screenshot and post on their social media accounts for engagement—are strung together with little flair. If there were something between the lines, some kernel of novelty in the complicated and endlessly workable depth of grief, this 100-minute vanity project could easily save itself from the dregs of streaming content. But that originality never arrives, despite Levy’s apparent confidence that it’s omnipresent.

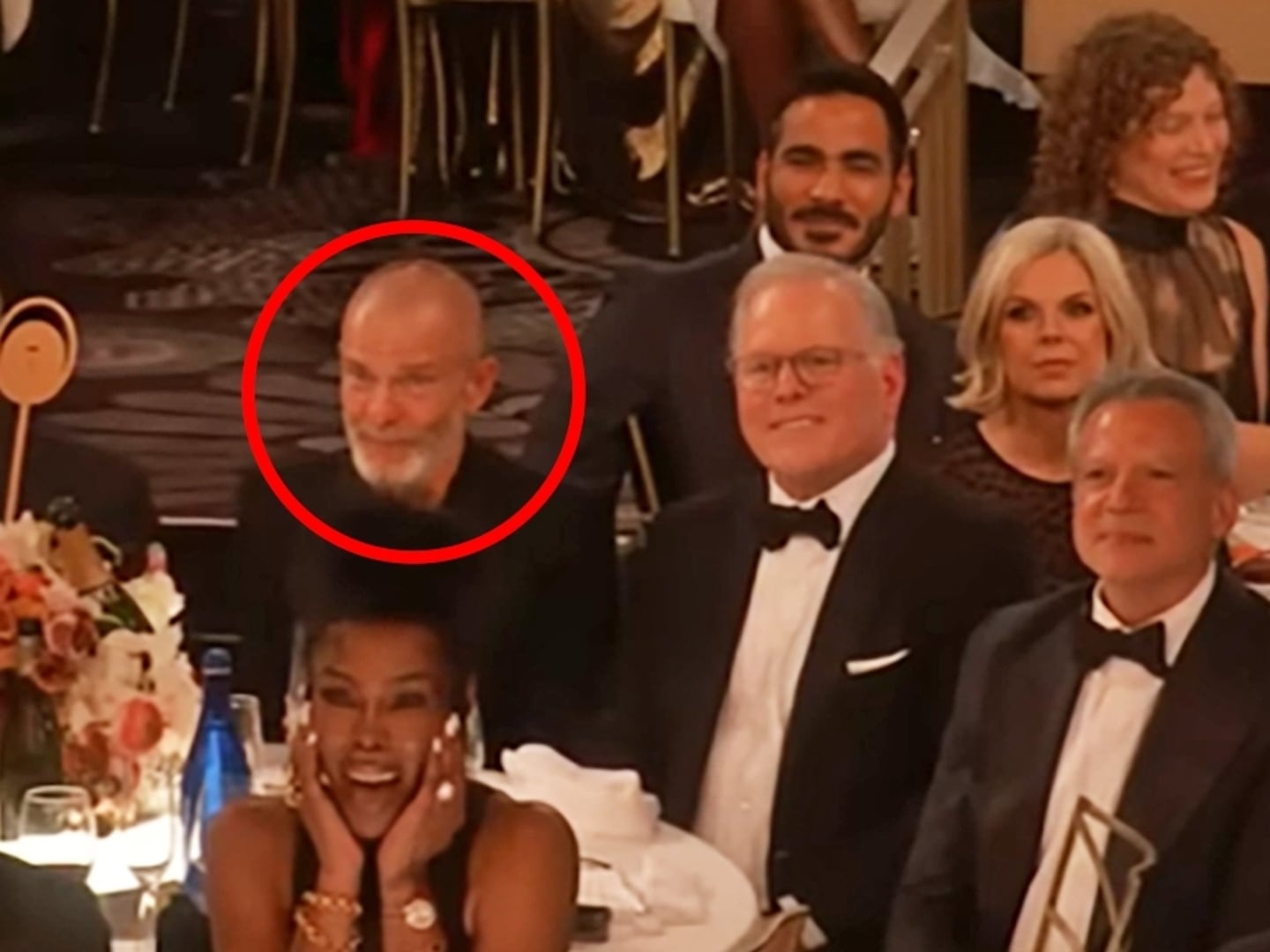

One of the film’s few saving graces is that it’s nice to look at, in the static way that a photograph that not many patrons are viewing in the corner of a museum is nice to look at. It’s pretty and well-staged, much like a CB2 store. In the film’s opening scene, set at a Christmas party Marc and his husband Oliver (Luke Evans) are throwing, this feeling of window shopping is somewhat pleasant. There’s a comeliness to this London flat held by two gay men for whom style is about having expensive things, curated with no taste. That’s a real phenomenon, one that attracts plenty of moochers for the free booze and warm lighting, including Marc’s two best friends, Sophie (Ruth Negga) and Thomas (Himesh Patel).

Thomas is grumpy because that is evidently the nature of perennially single gay men. Sophie is a barely functioning alcoholic, which we know from her character’s leaden introduction, where she’s asked how many drinks she’s had while nursing a crystal goblet. But these two poor souls and Marc are a family, and this family celebrates together regardless of its dysfunction. Oliver, however, can’t stay until the party’s end; he’s a popular children’s book author who must dash off to Paris for an early book signing at the Louvre. (Does Paris not have bookstores?) But the festivities are cut tragically short when Oliver’s cab gets into a fatal accident just a block away from their flat, for all of the partygoers to see.

If all of that narrative setup seems a bit crude, it’s because Good Grief is a shamelessly rudimentary film. Despite what Levy’s script is trying to suggest, the movie doesn’t have anything new to say, nor does it have any fresh way to structure the pieces that are supposed to get us there. When Marc finds out that Oliver had a secret apartment and a younger boyfriend in Paris, he surreptitiously proposes a group trip to the City of Lights with Sophie and Thomas, all on his late husband’s dwindling dime. Perhaps if there were a thoughtful rumination on how Marc’s mixture of grief, shock, and confusion caused him to make the kind of impulsive decision that people experiencing a major loss so often do, this plot point might be a welcome one. Instead, the vacation is just an excuse for Marc to continue rolling around his balled-up grief, and for Levy to keep opining.

It’s frustrating to watch Levy, a charming and charismatic actor, squander his talents across the board on his first feature film. But it’s even more disappointing to see him do the same to Patel and Negga, who have little to do but mope and drink in their time onscreen. Levy has called Good Grief a “love story about the importance of friendship,” noting that he wanted to explore the complexities of adult friendships in particular. But Thomas and Sophie are disappointingly one-note, with no character motivations other than trying to uplift Marc again and again, despite how many times he rebuffs their love. (Or, in Sophie’s case, have another drink—we get it!) But when it comes time for another hollow statement on the cosmic enormity of Marc’s grief, watered down further for the Netflix social team’s queued posts, his friends are all ears.

For such a personal film—Levy has also said that he wrote it as a tribute to his late grandmother—there’s little individuality or sweeping human truth to it. The movie boasts an utter lack of atmosphere, as Levy’s directorial eye does not yet seem to be sharp enough to hone in on anything that could be considered the beginning of a signature style. The pacing is choppy, making the movie feel so much more like smaller, self-contained scenes pasted together than it does a cohesive idea. And speaking of ideas, there aren’t a lot of those here, either. Levy pulls from the softness of ’60s-era Parisian romances and clumsily pairs them with the more blunt, melodramatic narrative writing of ’90s dramas. By the time Marc and his new, French date make their way into a museum after hours to gaze at paintings by dead artists and deliver lines like, “We are standing in a house of loss,” Good Grief feels like nothing more than an exercise in loosely quotable self-importance.

It’s a shame, because there is something here, some bit of fizzling matter that could be dredged up from Levy’s real experience with heartache. But Levy never makes it past the ego and into the soul to supply us with that honesty. There is an innate fear lurking in Good Grief, an apprehension to dig deeper. Films like this should not be relatable, they should be personal; examining the heaviness of loss and the ultra-specific nuances of it in your own life—and writing those things on the page—is what creates empathy among the audience.

But Levy’s film seems to be less about creating something as a form of processing emotions and more about making something for his career. It’s an admirable production if you view it as a first attempt at a new professional path, but one that leaves everyone who didn’t have a hand in making it entirely disconnected from that journey. And with thematically similar films like Spoiler Alert and All of Us Strangers released so recently, Good Grief’s reluctance to deliver anything other than insipid platitudes makes it feel like a cheap knockoff of a much more intimate idea.