In 2020, I wondered if Michael Stuhlbarg was “the most underrated actor alive.” Four years later, that question no longer applies, given that the 55-year-old artist has just been nominated for a Tony Award for Best Actor in a Play for his breathtaking performance in Patriots.

A ripped-from-recent-history play from The Crown mastermind Peter Morgan, it features Stuhlbarg as Boris Berezovsky, the Russian oligarch who amassed a fortune (and attendant power) in his native Russia during the heyday of Boris Yeltsin, and then aided the ascent of Vladimir Putin (Will Keen) to the president’s office, only to unexpectedly run afoul of the authoritarian. As the ambitious and idealistic businessman, Stuhlbarg is a larger-than-life marvel, capturing—with every cunning smile and imposing outburst—both the virtue and vice of the mathematician-turned-billionaire. A masterclass of showmanship that sympathizes Berezovsky without letting him off the hook for his personal shortcomings and strategic failures, it’s a tour de force that’s rightly earned raves since the production debuted stateside on April 22.

A portrait of that brief turning point in Russian history when Berezovsky and his free market-loving ilk took advantage of their new liberal environment to become personally wealthy as well as to push the country toward a new, more harmonious relationship with the West, Patriots is a lament for an opportunity lost, and a sharp and timely look at the ways in which autocracies emerge—or, in Russia’s case, re-emerge. Those themes are all embodied in the figure of Berezovsky, and it’s a tribute to Stuhlbarg’s immense talent that—paired with the excellent Keen as Putin—he brings them to life through formidable force of personality.

For the actor, it’s another in a long line of stellar turns (from A Serious Man, Call Me by Your Name and Shirley to TV’s Boardwalk Empire, Your Honor and The Staircase) that have made him one of Hollywood’s most dynamic actors. No matter the project, there’s simply no one better than Stuhlbarg. Consequently, days after his Tony nod, we were thrilled to chat with him about returning to theater, the complexities of Patriots, and the challenges of stage work.

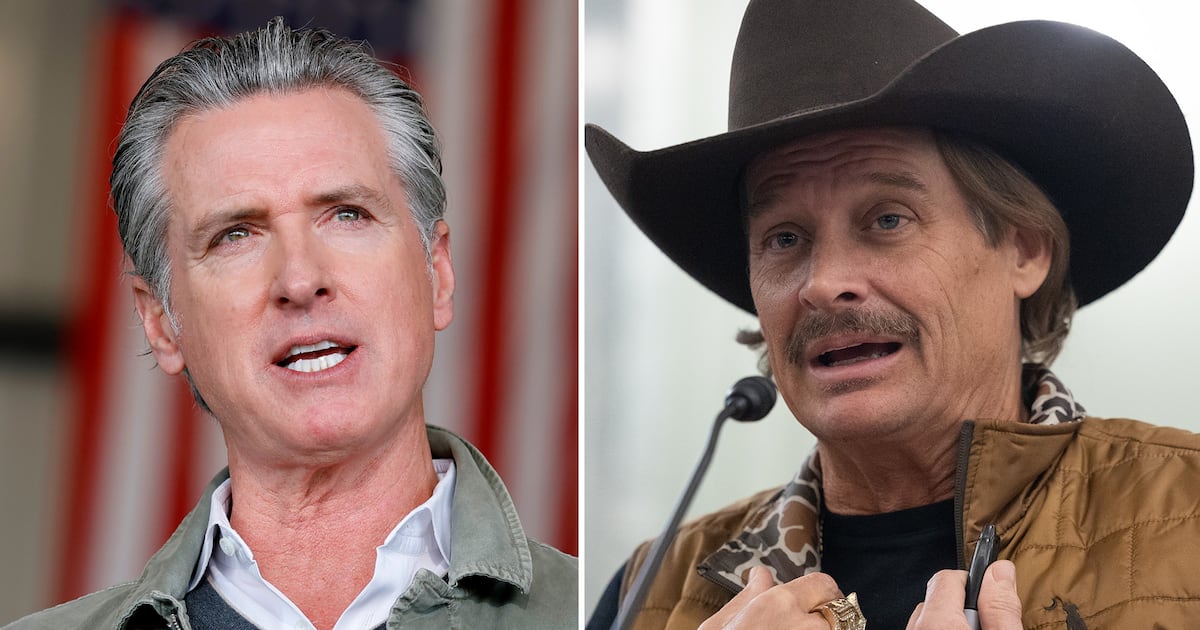

Michael Stuhlbarg as Boris Berezovsky and Will Keen as Vladimir Putin in Patriots

Emilio MadridFirst, I want to say congratulations on your Best Actor Tony award nomination, the second of your career, following [2005’]s The Pillowman. Did it come as a surprise, or do these things get tipped off ahead of time?

I never expect anything. I just jump in because I want to be working on something and if things like this come along, I’m absolutely grateful and delighted that the show is recognized in one way or another. Hopefully, it just means that more people will come. It’s a blessing.

Patriots paints a less-than-flattering portrait of Vladimir Putin. Even though it debuted in London two years ago, was there any hesitation about being front-and-center in a play that’s critical of an autocrat who’s known to do away with both real and perceived enemies?

It is a kind of origin story, and it’s directly correlated to the life of Boris Berezovsky in particular, and so in some ways, yes, even though Mr. Putin’s life continues and his leadership of Russia continues, this is a story within a particular period of time. It mostly centers on Berezovsky’s life. However, it’s always in conjunction with Mr. Putin, and how the modern-day audience can take what they know of the present-day Mr. Putin and marry it together with some information about him that they may not have known.

These are all things that had been said about Mr. Putin previously; it doesn’t necessarily bring up anything that is new. However, those things that are discussed still reverberate with us today. So in some ways, it is a history play, and in other ways, as is the case with history, it still has resonance and relevance to our lives today. In that way, perhaps, it could be a touch subversive. But it’s not addressing who he is today. It may circle around who he is in general, and what his pathway has been. I guess that’s what I’ll say about that!

Did you research Boris Berezovsky on your own, or in cases such as this, do you stick to the script?

I personally was really interested in digging into Mr. Berezovsky’s life and learning about him as much as possible. At the time the play was done initially, and even perhaps now, I’m not sure how many people knew about his story. I think the impetus behind my pathway into this was to learn about the man himself, and how he communicated. I looked at his interviews and tried to marry what I learned about him with what Peter’s story chose to illuminate. It was really a combination of those things, and the collaborative efforts with the other actors as well as with our wonderful director Rupert Goold, in terms of trusting Rupert completely about which elements he felt were necessary to include and which ones wouldn’t be.

When you’re stepping into a role that’s been previously inhabited—as with Boris, who was played in London by Tom Hollander—do you avoid seeing the prior performance so you can create your own unique version of the character?

I did not have the benefit of getting to see Mr. Hollander’s performance, so I don’t know what it was he did. I’m a huge admirer of his, and just the fact that he jumped in and had a go at it was enough for me to absolutely take a look at it and to learn about what the other actors went through when they were tackling the material. It wasn’t a staid museum piece; it was something that continued to be written as we rehearsed it. Peter was still writing and would take things away and add things, and it still had its own unique life as we continued to work on it, which these things, in my opinion, should. They should continue to grow and change with each group that works on them.

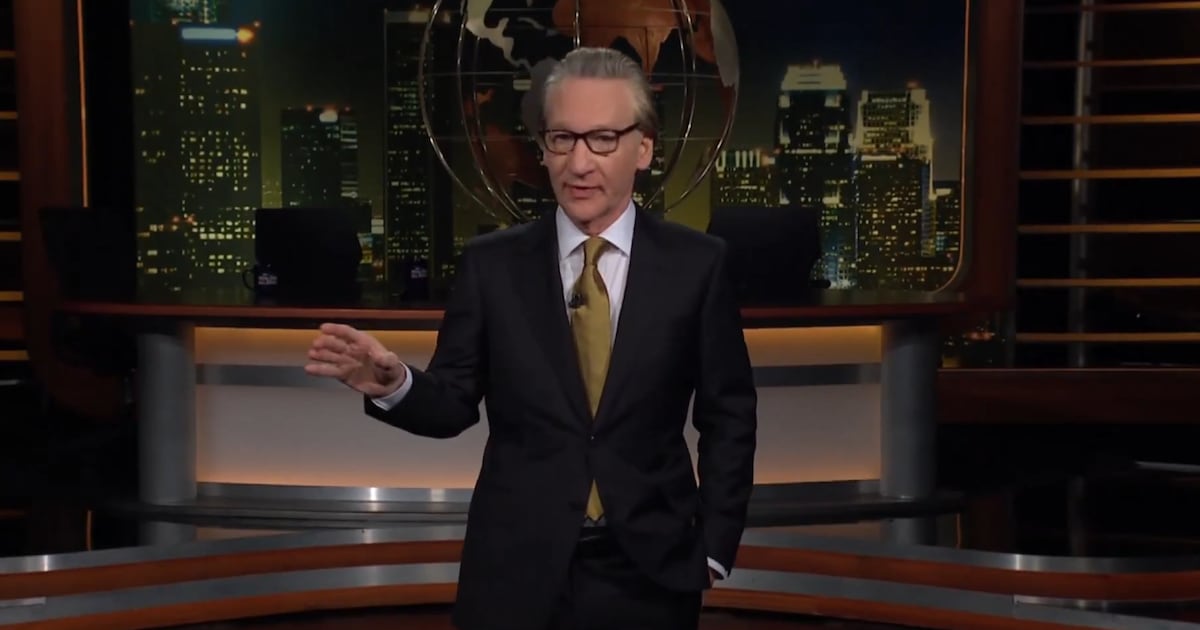

Patriots on Broadway

Matthew MurphyAll that being said, the production itself had its DNA somewhat already in place, and in some respects, I was put through the paces of learning the movement of how the piece worked. Certainly, I was walking in his footsteps initially—or so I imagine; I’ll never know for sure because it’s our experience. But I never felt like there was any real comparison because I didn’t know what had come before, and that served me very well, I think.

I imagine it’s not the same situation as, say, playing Hamlet and trying to block out the myriad performances that have preceded your own.

If you’re talking about creating a Shakespeare role, and you’ve seen Antony Sher and Laurence Olivier and everyone who’s played Richard III before, and you have those impressions in your head, I find it difficult to separate what my own choices might be, knowing other people’s choices and having them in my mind while I’m trying to create something fresh. Yet at the same time, if something works, it works, and you can also think of it as celebrating a discovery that someone made in the past, and saying, I want to celebrate that by incorporating it into my version of what I think this could be.

In this instance, that wasn’t the case, so I adhered as closely as I could to the real Boris until Rupert suggested that maybe we can loosen it up and to start separating who my version of this man might be. There are Shakespearean resonances within this play as well. There are elements of Henry V’s St. Crispin’s Day speech in him rousing the oligarchs. There is Boris considering himself to be a little bit like Rumpelstiltskin and Richard III, and there is the indignation of Richard II.

There are elements of Shakespeare that resonate for me all the way through the play. I can recognize them and appreciate them, and yet I can play our play for when it’s supposed to be set, and recognize who I believe this man seemed to be. At the same time, as Peter’s script is an invention as well—or historical fiction—in terms of the creation of the dialogue, we still have freedom to own it in our own individual manner.

The first scene of Patriots is an energetic showstopper. Is it difficult being that big on stage, right out of the gate?

It’s like being shot out of a cannon, and you just ride the wave of what it is that’s on the page for you to do. Plus, the pace of it—it moves so quickly that it’s meant to be a whirlwind to throw the audience into the hurricane of who Boris is, and what his life was like at a very exciting time, and what each day may have brought into his life. So in one way, it’s really fun, once you know it, to just ride it.

To navigate each audience, it’s always a little different each night. It’s a thrilling challenge, and it’s breathtaking to do, which is great, great fun. There are several places during the play where I go running off the stage and just find myself having to stay very, very still, catch my breath, have a little water, and then move on to what the next piece will bring. It is a juggernaut, and like a decathlon if all events were done one after the other after the other.

It’s thrilling to play, and you don’t have time to think, which has been a watchword for me throughout this entire process. To do, not think. To understand it in a way that you don’t have to think about it. It’s about reaction, which is wonderful. And it’s been so fun to do with this group of actors.

Actors often love theater because, through repeated performances, it lets them dig into a character in a profound way. But is that also one of its most difficult aspects, because you have to keep re-locating the same emotions and beats, over and over again, to keep it fresh?

Understanding that each night is a new night, and each performance is a new go at it—I think even if you put your intention completely behind trying to do the same exact thing night after night, it’s always going to be different. I think that’s one of the reasons why it’s always an education and always fun to do plays—every time you do it, you learn something. Often, that means falling flat on your face or not getting the reaction you hoped to get. And other times, when you’re completely into it, you’ll get a reaction that you never thought would be possible for something.

It’s the thing about acting in general that is amazing to me. If you apply yourself to it, thoroughly, it will continue to deepen and surprise you. It is a discipline to honor, and really a miracle that treasure continually becomes unearthed, every time you dig. But you really have to apply yourself. So showing up is important. And by showing up, I don’t just mean being there, but engaging and investing, being present, and caring. Because when you do, it’s like practicing anything. The more you practice the piano, the better you’re going to get. Or learning a foreign language. At first, it’s very muscular and you’re overworking yourself. Then the day will come when you’re completely exhausted, but you’ve done it so many times, your body knows it as muscle memory, a dance. I think the term is mnemonic, where you’re in it and you’re not thinking about it. That’s when the magic can happen. Because you’re not controlling it; you’re riding it and it’s riding you, and new things blossom.

There is the dread of a two-show day [laughs]. There is the fear of not being able to do something as you did it before. However, understanding that it doesn’t need to be the same is valuable. It’s work on a story, each night. It is a new night, it is a new opportunity, with new people. You will learn new things, you will fail differently, and you will succeed differently, most likely. It is a rigorous practice, and it is unrelenting and thrilling at best.

Were you eager to return to theater, where you began your career?

I’m grateful for this opportunity, really, because theater was my life for many, many years. It was all I did from 1989-2008, and then my life took a left turn, and all of a sudden it became all film and television. It’s not something that I made happen; it just happened that way. I still love the theater. It’s just that the opportunities that came along were opportunities that I didn’t want to pass up, so I jumped at them. Over the last number of years, I’ve had the opportunity to do a couple of really challenging roles, and that’s been thrilling as well. The older I get, the more I understand that you have to choose things carefully because a play is such an all-encompassing venture. It really dictates your life every single day for the length of the run. You’re thinking about what you’re going to be doing and how to reserve your energy between the hours of such-and-such.

Patriots isn’t a musical but you do get to perform a brief song and dance number. Were you happy to have that chance on Broadway?

It’s how I got my start, actually—doing musicals as a kid, in our community. Musicals were my first dipping into the theater. My parents had original Broadway recordings of many, many plays, and music was my way in. Music has been a big part of my life, and I do love to sing. It wasn’t something I sought out at all, but it is always a challenge and something I have great respect for. It’s something that some people have huge gifts for, and I have an appreciation for it, and I’ve always been surrounded by people who had tremendous natural gifts for it.

Michael Stuhlbarg as Boris Berezovsky in Patriots

Matthew MurphyI always put myself in the category of an actor who enjoyed singing when he had the opportunity, but wasn’t necessarily a singer. Even though my grandmother sang and played piano on the radio in the ’30s on one side of the family, and my grandfather on the other side of the family played the piano. Music has been a part of my life, and I play guitar and saxophone and was in choir. It’s something I’ve loved, so to get to sing a little bit is a delight to me. But it’s never something I would ever force on anyone unless it was a part of the piece! [laughs]

Netflix is producing the Broadway production of Patriots, and there’s word that Peter Morgan is working on a screen version. Any news about that—and/or your participation in it?

I have understood that, yes, it may be his intention to go ahead and turn this into a piece for either television or film, and I think that’s wonderful. As anything that transfers from the stage to the screen, it will have its own life, separate from what it is that we are creating night after night. It’s been a remarkable challenge and I’ve had an exhilarating time being a part of the stage version of it. Were it to continue into that next phase, that’s entirely in Peter’s hands and mind, and what he chooses to do with it.

If indeed it happens, I’m sure people will find it to be engaging. But there has been no discussion in terms of utilizing our experience. As a jumping-off point, I’m sure it has been, because he continues to explore the material and to figure out which story it is he wants to tell. I’m sure if or when it ends up on a screen somewhere, it will be another incarnation of it altogether. Netflix has been a producer of our show, and supporting Peter’s vision of this story, so I think it could be thrilling for folks to see what it turns into. But there has been no discussion of that, as of yet, in terms of if it will happen, when it will happen, and who will be a part of it.