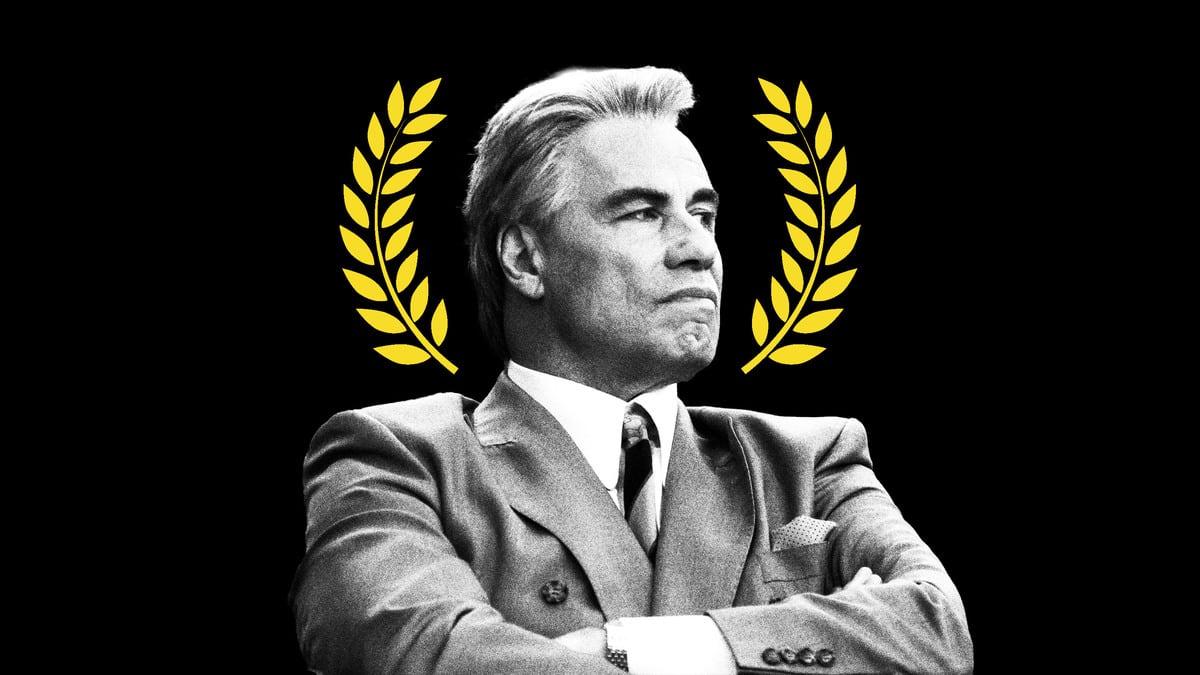

Five years ago to the day, the John Travolta-starring mobster movie Gotti dropped into theaters, bombing so hard that I hear Christopher Nolan studied it to make the explosion in Oppenheimer even more lifelike. Unlike its titular Don, Gotti was essentially a laughing stock. It made a paltry $6.1 million at the box office, against a $10 million budget, and hobbled out of its brief theatrical run with cinder blocks strapped to its feet.

No doubt about it, Gotti was a certified dud. The film is overcomplicated, underwritten, stereotypical dreck, the kind of movie that Martin Scorsese probably uses as an icebreaker at dinner parties, when he hands his guests a DVD copy to use as a coaster. My dear colleague Nick Schager wrote at the time of release that the film “[overflowed] with so many awful Italian accents, it [came] across as borderline bigoted.” The review succinctly summarized the overall travesty in its headline: “Gotti Is the Most Hilariously Bad Movie of the Year.”

Even though the film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival—where critics sometimes over-exaggerate the quality (or lack thereof) of a film while under the spell of the salty sea air—reviewers were no kinder a month later when it had its theatrical release. Gotti ended up with a 0 percent approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes. So, in a last-ditch attempt to save the movie from bargain bin hell, its press team created an advertisement attacking the film’s critics that was so wildly brilliant (and so incredibly bitter) that its desperate pleas still live in my head to this day.

The ad, which was uploaded to the Gotti movie’s official YouTube account, begins with a questionable statement: “Audiences loved Gotti…” (Did they really?) This garish wall of text clunks down into the ad with all the sophisticated design expertise of a toddler playing around in Adobe Premiere Pro (the free version, that you can get on your phone). A soundbite of Travolta saying, “Nevah back awf, evahr” lands just before another string of text plunges with a thump: “...Critics put out the hit.”

“Critics put out the hit” has remained seared into the prefrontal cortex of my brain for the last five years. Every single time that I, a critic myself, end up reviewing something unfavorably, “critics put out the hit” blasts into my mind. Comparing a film critic to a homicidal mafia boss is one of the single funniest things that anyone has ever done. It’s as if I walk out of a movie screening, kiss the film’s poster twice, and let my goons take care of it. But the ad isn’t over yet, there’s one more ingenious line of copy, that should really be taught in advertising programs: “Who would you trust more: yourself, or a troll behind a keyboard?”

Of course, the actual advertisement isn’t even that grammatically correct. This is Gotti, after all. You think grammar was in the budget? That costs an extra stack.

The sentence, “Who would you trust more: yourself, or a troll behind a keyboard?” has been bopping around my head quite a bit lately. I’ve noticed that, in the five years since Gotti was released to a blanket of boos, the response to professional criticism has become somewhat more—ohhhhhh, how do I put this—vitriolic. But before you start click-clacking your fingers away to come into my Twitter mentions, let me explain myself a bit.

The rise of social media has given a massive, legitimate platform to critics with a broad variety of backgrounds, a necessary step toward finally leveling the point of entry for aspiring critics. Social media has also allowed artists whose work is up for debate to have their say too, if they so choose. Perhaps, to some degree, equalizing the playing field between creator, critic, and fan has also contributed to an audience’s distrust of criticism.

For example, let’s take the new Tom Holland show The Crowded Room, which boasts a cast of stars whom I usually enjoy, but a hackneyed story so languid and obvious that even its magnetic cast couldn’t elevate their material. Other critics tended to agree, giving the series a low critical score on Rotten Tomatoes. In response to that rating—and the discrepancy between the show’s critic score and audience score—Twitter users became suspicious. “This ain’t crazy to y’all? There’s something fishy, the audience knows what’s real,” one user tweeted, with a screenshot of the different scores: 18-percent from critics, 97-percent from audiences.

While Rotten Tomatoes was a game-changing tool both for making criticism accessible and legitimizing independent critics, it also allows its general users to rate projects. That can sway the metrics of the audience score if, say, fans of Tom Holland take to the platform en masse to rate the show positively, without having seen the entire series. Holland even responded, thanking his fans for watching and rating the show well. Rotten Tomatoes, with its flashy colors and binary fresh-or-rotten scale, is an easy-to-understand aggregator of criticism, but it’s just that: an aggregator. The site is not meant to be the Godly, defining opinion, but the prevalence of these scores appearing in advertising or physical packaging would like you to forget that as soon as you see that “certified fresh” tomato.

Artists themselves have had a hand in implying critical distrust as well. Back in March, Seth Rogen told the Diary of a CEO podcast, “I think if most critics knew how much it hurts the people that made the things they’re writing about, they would second guess the way they write these things.” (Never mind that honesty is an integral part of good criticism).

Just last week, pop star Charli XCX took to Twitter to call critical reviews “kind of silly,” asserting that these writeups are “more about the culture or the scene that surrounds an artist.” Charli’s comments stirred up a mixed response—even among her own diehard fans—with most agreeing that criticism is meant to start a conversation, and reflect a specific critic’s interests and feelings. Hell, even Gotti garnered some reviews with nice things to say, like Entertainment Weekly’s praise of Travolta’s performance.

There’s no way that a professional critic can talk about the public’s response to criticism without seeming like they’re complaining from a mountaintop. (In my case, it’s really more like a discounted office chair from Wayfair.)

But maybe you could do me a solid, and try to believe me when I say that criticism is not meant to be a static opinion, that singularly defines a piece of art forever. Reviews are intended as a guide for the audience and the artist, a mirror of the moment when a piece of art is released into the world. These assessments can change and be reconsidered over time. Because in the end, it really is up to the audience to decide what they want to spend their time and money on. Us trolls behind the keyboard are just trying to help make that decision a little easier.

Keep obsessing! Sign up for the Daily Beast’s Obsessed newsletter and follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and TikTok.