When it comes to imbuing characters with emotional nuance, making fun of your icon status with terrific comedic timing, or gritting your teeth into a patient smile while James Cameron delays Avatar sequels, there is no better actor to call than Sigourney Weaver. She is a Hollywood legend for a reason—able to do just about anything, and capable of turning even the most bland material into admirable work. Weaver is so talented, you might think there is nothing she can’t do. But we all have our shortcomings, and even the sensational Sigourney Weaver can’t perfect a convincing Australian accent.

Unfortunately for Weaver’s new limited series The Lost Flowers of Alice Hart—adapted from Holly Ringland’s 2018 novel and premiering on Prime Video Aug. 4—a believable accent is sort of a requirement. The seven-episode drama series is set in the lush landscapes of the Australian coastlines, where June (Weaver) presides over a flower farm called Thornfield that doubles as a safe haven for abused or orphaned women and girls. When June’s granddaughter, Alice (Alyla Browne as a child and Alycia Debnam-Carey as an adult), survives a horrific fire that kills both of her parents, June welcomes her to Thornfield. There, she teaches her the language of their flowers, which beautifully mask dozens of dark family secrets.

Though Weaver’s accent seems to come from somewhere between the States and the English countryside, it’s not necessarily a hindrance to the show—the series holds itself back just fine. The Lost Flowers of Alice Hart is both frustratingly convoluted and, at times, quite emotionally stirring. But the former clouds the latter, with extremely dense writing and ornate storytelling constantly hampering and unsteadying the series. Weaver and Debnam-Carey act through these glaring issues with grace; combined with the series’ stunning visual landscape, their performances are almost enough to keep the series afloat. But by its hard-won endpoint, The Lost Flowers of Alice Hart wilts under the weight of its own ambition.

Alice Hart’s entire first episode is dedicated to its flowery (pun intended) worldbuilding. Initially, that’s a benefit to the show. The introduction to a young Alice’s family sets the tone for both the series’ writing and its sumptuous setting. Alice’s childhood, living in a remote cottage with her pregnant mother Agnes (Tilda Cobham-Hervey) and her father Clem (Charlie Vickers) at first seems idyllic, until we begin to understand that their isolation is intentional. Clem is emotionally and physically abusive toward his wife and daughter, but he veils the shame and wickedness of his violent outbursts with apologies and gifts of beautiful hand-carved wooden trinkets. As it typically goes in these cases, Clem’s presents only disguise more brutality, waiting just around the corner.

These scenes are difficult to watch, but a capable-beyond-her-years Browne is absolutely magnetic as younger Alice. Her bright talent is a lovely contrast to the brooding, cloudy scenery that surrounds her home, which is captured magnificently by calculated camerawork and enhanced with terrific color grading. Those aesthetic pleasures last throughout the series, past the suspicious fire that kills both of Alice’s parents and sees June, who had been estranged from her son Clem, bringing Alice to Thornfield by the end of the premiere. Just as Alice comes to find, when June introduces her to their sanctuary’s flower dictionary—which uses plants to communicate sentiment—The Lost Flowers of Alice Hart is reliant on visual language to convey its messaging.

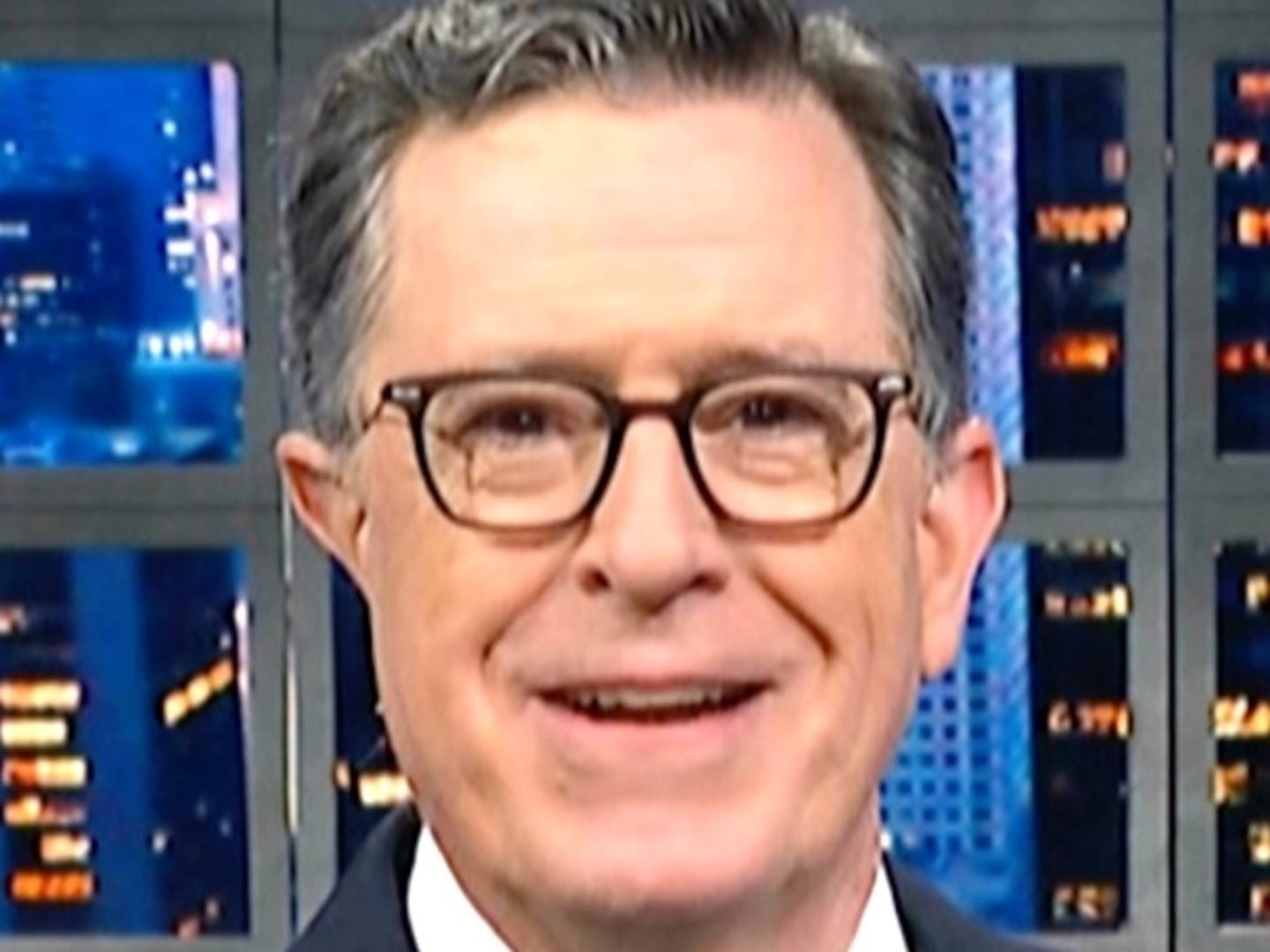

Sigourney Weaver and Alyla Browne.

Hugh Stewart/Amazon StudiosThat’s a clever tactic for the first few episodes, but considering that The Lost Flowers of Alice Hart consists of seven hour-long installments, that ingenuity withers fast. I wouldn’t consider the series a slow burn so much as a deliberately obtuse creation, one that assumes its labyrinthine narrative equates to powerful insights about human nature. That’s not to say that those perceptive ideas don’t take root in the series at all. It’s just that they’re buried underneath so many overblown ideas and character threads that the central themes often feel like an afterthought.

Though she has taken asylum at Thornfield, Alice’s life remains complicated. Her abusive childhood, compounded by the fire, have left her mute. Thornfield—which is gravely misunderstood by surrounding towns—alienates her as much as it serves as her refuge. It doesn’t help that June is wound tight, holding the mysteries of their family close to her chest so Alice’s curiosity can’t get the better of the two. But when Alice finds an inscription in a book that proves her mother was a resident at Thornfield, the picture-perfect way of life at June’s compound begins to crack.

If only it didn’t take three hours into the series for that to happen. Even after that initial revelation, answers do not come easily; by the end of the third episode, most of them are still shrouded in hazy foliage. By keeping most of the series so steeped in mystery, The Lost Flowers of Alice Hart makes its titular character’s development far less compelling than it should be. All those secrets create intrigue, but it becomes difficult to connect with a character’s growth when viewers have so little context for the darkness they’re overcoming. In some cases, the withholding narrative might successfully increase the tension. Here, it cuts the stakes down entirely, turning anticipation into persistent frustration.

That exasperation would be nearly impossible to reconcile if it weren’t for Debnam-Carey and Weaver’s keen pair of performances. Alice might flee Thornfield after uncovering more truths (which are, again, only the tip of an iceberg that takes far too long to come to the surface), leaving Debnam-Carey and Weaver to act apart from one another for most of the series’ latter half. But the two women still feel as though they’re performing opposite one another. Weaver’s expressions bear the weight of June’s remorse over her son’s violence and her inability to break the cycles of abuse that tormented her too. Debnam-Carey complements this heaviness with breathless freedom, which transforms into youthful naivete that eventually brings the pieces of The Lost Flowers of Alice Hart’s puzzle together.

The series’ wonderful finale ultimately begets disappointment. A satisfying ending is far from enough to negate the show’s flagrant pacing problems, which could’ve been solved if this was a film adaptation, and not a limited series. I doubt that the show’s thematic content, though at times captivating, will be enough to encourage most viewers to see the series through to its end. Those who prioritize style over substance will find an endless amount of enthralling cinematography to admire here; The Lost Flowers of Alice Hart is one of the best-looking shows of the year so far. But like an exotic flower, a story this sensitive needs constant tending, and the budding Alice Hart never reaches full bloom.