For as much as studies of grief and death have been twisted and mangled into trite gimmicks in the genre films of late, it’s rare to see a manifestation of the reaper that doesn’t come in the form of some horrific demon or protracted paranoia. Toni Collette’s grief got her family sucked into a cult in Hereditary; Natalie Portman grappled with her husband’s disappearance by venturing into a mutated Earth in Annihilation; sorrow was even portrayed as the literal Boogeyman in last summer’s lazy film of the same name. And, of course, there was the top-hatted apparition in The Babadook, the film from the past decade that’s easiest to point to when examining the abstract ways in which grief can be portrayed in cinema.

But in Tuesday, the feature film debut from writer-director Daina O. Pusić, death appears in the form of something much more unusual: a mutating, talking macaw (voiced by Arinzé Kene). This strangely beautiful vision of Death flies around the world, killing every living being—from house flies to humans—when their time comes. In the film, Death arrives at the home of Zora (Julia Louis-Dreyfus) and her terminally ill teenage daughter, Tuesday (Lola Petticrew), who suffers from an unspecified illness that keeps her in chronic pain. Death assumes that helping Tuesday pass on will be business as usual, but both her bright spirit and appreciation for the world stop him in his tracks. Before long, the world’s balance is thrown out of whack, and when Zora further intervenes to save her daughter’s life, Tuesday morphs into something as truly fantastical as it is frustrating.

At the top of the film, we meet Zora after she leaves Tuesday for the day, at home in their London flat with a visiting nurse (Leah Harvey). (When the nurse’s caller ID pops up as “Nurse 8” on the phone, Pusić cleverly doles out plenty of exposition with just one quick frame.) Zora visits a taxidermy shop where she tries to pawn off a collection of four stuffed rats, dressed as different members of the Vatican. An off-color joke to the shop owner lands with a thud, and we come to understand how Zora is handling her daughter’s declining health. Pusić balances a penchant for brash humor with Zora’s feeling that she’s dragging despair alongside her all day. Her crude jokes are little attempts at coping, ones she doesn’t even realize she’s making.

When Death appears before Tuesday while Zora is out during the day, the film begins its extended period of separation between mother and daughter, resting too long in its weakest stretch. Besides the fact that birds are frightening enough as it is, Death is an intimidating creature who can change sizes at will. Though Tuesday is frightened by what she knows is a vision of her demise, she remains steadfast by working through her fear, repeating her inner narrative to breathe in and out at a constant pace. It’s this monologue—and Tuesday’s wise idea to tell the bird a joke—that moves Death, who holds off on his plans for the young girl.

On common ground, Tuesday and Death bond together, and she brings the bird inside to remove glue, left over from a rat trap he visited, from his talons. With this act of kindness, the echoes that fill Death’s head from creatures around the world, begging to die, dissipate. The macaw might be the reaper, but he is still bound by physical limitations, and it’s how Tuesday helps him transcend his bodily constraints that makes Death sympathetic to her plight. It’s here where Pusić begins to ask some engaging existential questions, only for their answers to become muddled when Zora returns home and is confronted by the presence of Death in her home.

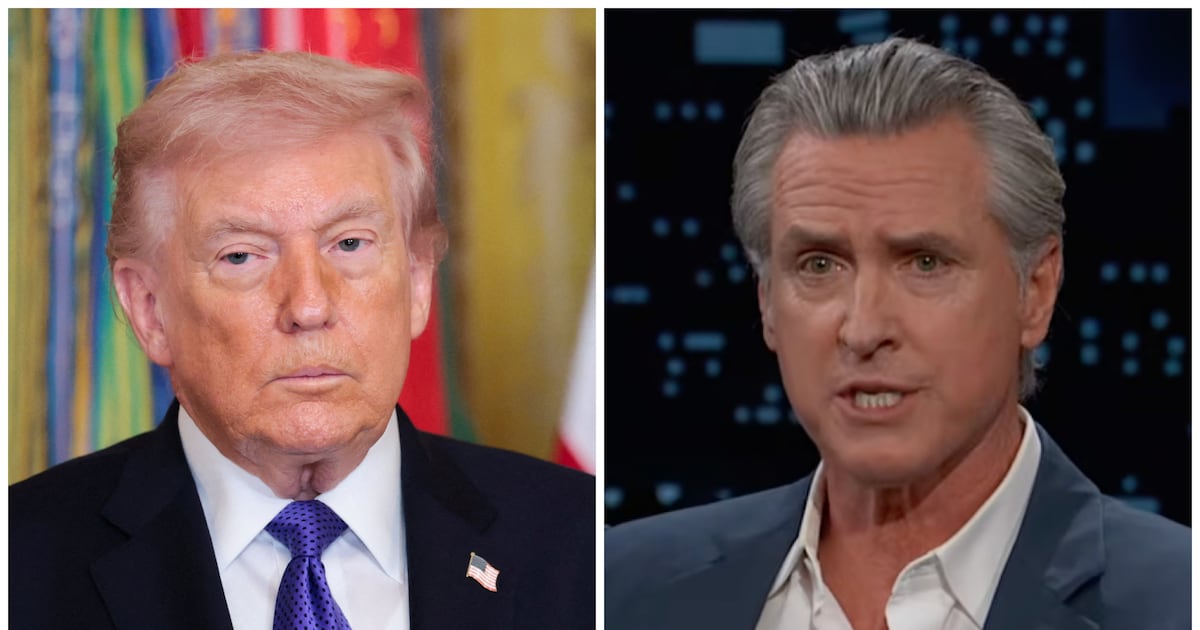

Lola Petticrew and Julia Louis-Dreyfus.

Kevin Baker/A24Pusić’s script is consumed by how humans bargain with death, but why she is so enamored with that stage of grief specifically is never quite clear. As a director, however, Pusić comes close to making her jumbled intentions irrelevant. Her touch is stylish and colorful, and the film’s sound mixing is some of the best in any studio film this year. The writer-director makes her chimerical version of the world vibrant and alluring, even at its bleakest. There is a genuine tenderness to the way Pusić portrays interactions between people that transcends some of her more cringe sensibilities. (Death vaping alongside Tuesday is certainly a sight to see.) And her knack for combining grotesque imagery with conventional, human beauty is a sight to behold. In that respect, the world that Pusić crafts in Tuesday feels reminiscent of those found in the fanciful—yet often grim—stories of Roald Dahl.

It takes a dedicated and fearless performer to pull something like that off, and Tuesday finds that in Louis-Dreyfus, whose turn in the movie is her best dramatic part to date. As Zora, Louis-Dreyfus tempers the film’s eccentricities to bring the story a necessary shot of humanity. Whether she’s cracking a lewd joke to Nurse 8 or swallowing all of the shock of Tuesday telling her mother that she is going to die soon, Louis-Dreyfus is nothing short of riveting. The way she looks at Petticrew throughout the movie bowled me over. Zora wears her grief like a stain: embarrassed by its existence but trying not to let on to her shame. When Zora realizes just how much time she’s losing with her daughter by avoiding the truth, Tuesday blossoms into its stunning climax, finally learning how to balance its show and tell.

Leah Harvey and Lola Petticrew.

Kevin Baker/A24But as Tuesday stretches on, and Louis-Dreyfus masterfully takes center stage, the drawn-out storytelling that makes up the film’s first half tastes all the more sour. Louis-Dreyfus’ compelling performance begs for more time alongside her onscreen daughter, and that Pusić only meaningfully brings the two together when the movie is already half-finished is a baffling choice that hampers Tuesday’s emotional resonance. While it would be a waste of time to gripe too much about the fantasy elements clouding the passion in a movie about a grunting, gravel-voiced angel of death macaw, these components still keep the film feeling confused, even if that narrative chaos is intentional.

Despite that, it’s impossible to deny Pusić’s ambition. Hers is a bold vision, which crystallizes in the film’s final leg. It’s in that last half-hour where Tuesday shrewdly illustrates how oblivious we are to being surrounded by death at all times. It’s omnipresent, yet despite its ubiquity, death remains the most difficult thing in the world to confront. Pusić finds fresh and endlessly interesting ways to remind us of that, even if the film is sometimes too tonally chaotic and offbeat for its own good. But for all of Tuesday’s imperfections—and there are many—you can’t call it unoriginal. In a sea of exhausting cinematic sameness, when you can buy a ticket to any one of the multiple grief allegories playing at your local movie theater at any given time, a little novelty goes a long way.