In December 1866, an advertisement in the Annapolis Gazette advertised the “public sale” of a 30-year-old woman named Dilly Harris. Dilly had been found guilty of petty larceny and had been sentenced to be sold for a period of two years. For the passersby who saw her auctioned off on the steps of the courthouse that holiday season it was a familiar sight, the only striking element was that that the 13th Amendment had been passed into law the previous year. While it might seem as if slavery had been abolished in 1865, the 13th Amendment had an exception clause.

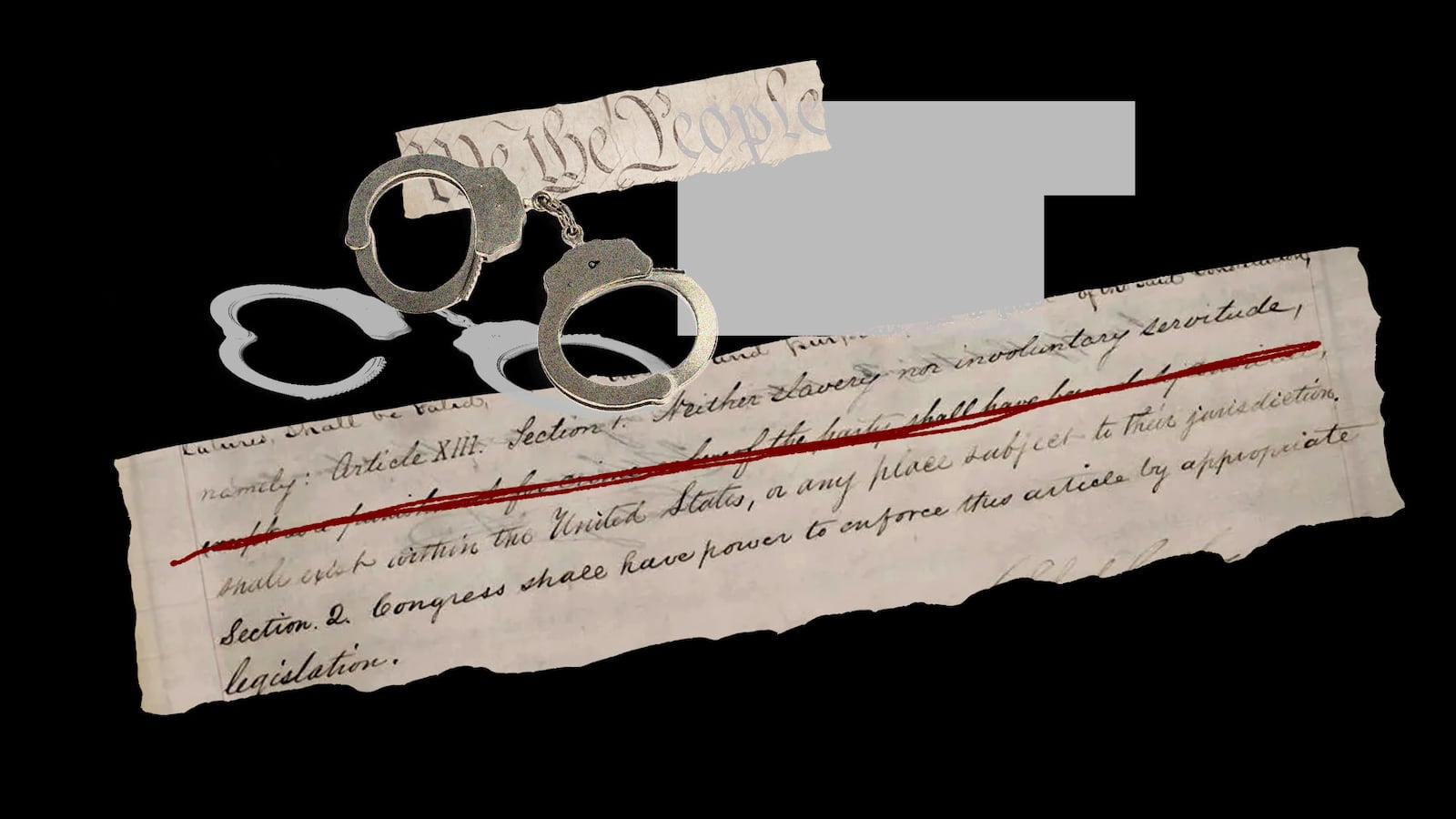

Tucked between two commas is a loophole: Slavery and involuntary servitude could continue to exist “as a punishment for crime.” And it did, not only in Annapolis, but in places where convict labor took the place of slavery. But next month, five states—Alabama, Louisiana, Oregon, Tennessee, and Vermont—will vote to abolish the clause permitting the coerced labor of convicted criminals.

Though the penitentiary is a relatively recent phenomenon, the prison is nothing new. The United States is hardly the first society to put condemned prisoners to work. Under ancient Roman law low status people known as humiliores—that is “the poor,” the socially disadvantaged, manumitted people, and enslaved people—could be put to work in “public works” or in the mines (the wealthy, meanwhile, might receive fines or be sentenced to exile).

The pioneering archeological work of Matthew Larsen and Mark Letteney, authors of Ancient Mediterranean Incarceration (University of California Press, forthcoming), gives us a sense of what life in the Roman mines was like. Larsen told me that “most people’s day-to-day looked like waiting in a carceral facility for months on end waiting one’s turn to go into the mines and use a tool to extract a metal. This labor looked like swing a pickaxe into a wall of the mine over and over again.”

In a recent article on prisons in Roman North Africa, Larsen explores the cramped and dark spaces of Roman mines. Pliny the Elder writes that prisoners often would not see daylight for months. Strabo tells us that the work was painful and the air “deadly and difficult to endure.” Some mines, like the copper mine at Umm al-Amad near Wadi Faynan, Jordan, could be accessed only by crawling. In others it was possible, with various amounts of difficulty, to walk upright. But the experience was damaging to the body and the working conditions were dire. Beyond the tattooing, branding, head-shaving, beating, and shackling that took place there, the work hurt. The mines could leave prisoners with permanent health problems and deformities. In what Larsen described as a “haunting parallel to our… prison-industrial complex” some mines, like the yellow-marble mine at Simitthus (Chemtou, Tunisia), housed over 1,000 people, had a guard corridor, and a tower.

Those Roman-era criminals who were not consigned to the mines often found themselves working closer to home in mills and bakeries. Pliny mentions that in Campania, Italy, there were wooden mortars run by convicts in chains. Callixtus, an early third-century bishop of Rome, was allegedly placed in a mill to do hard labor, before being scourged and dispatched to the mines of Sardinia. It was only after this that he returned to Rome and became what we now call Pope.

While some forced workers, like the prisoners put to work by the Ottoman Sultan Mehment II in the wake of his military expansion in 1453, received a small wage, most did not. The prisoners who were housed in the Inquisitorial palace in Palermo in the 17th century often received sentences of five years in the royal galleys. They were sometimes accompanied by chaplains to school them in the “true faith.”

In the case of the United States, the racialized histories of enslavement and incarceration are apparent to even the most casual student. In the aftermath of the Civil War, convict leasing became the preferred form of punishment in Southern states. Convicts worked on municipal, county, and state prison farms; constructing roads and railways; and were leased out to individual contractors. Here they lived in the same spaces, were fed the same food, and faced the same forms of corporal punishment as enslaved people had a few years earlier.

The system could prove fatal, but usually only to people of color. As David Oshinsky shows in his book Worse than Slavery, convict leasing was deeply racialized from the start: In 1882, 126 of 735 black state convicts died. By contrast, only 2 of 83 whites passed away. “Not a single leased convict,” writes Oshinsky, “ever lived long enough to serve a sentence of 10 years or more.”

Though we tend to think of the convict lease system and the chain gang as male spaces, women were also sentenced to convict labor. Sarah Haley’s work on women in Georgia reveals that white women were only rarely imprisoned and were almost always exempted from convict lease camps. As Talitha LeFleuria’s work discusses, those women who did find themselves in the convict lease system were routinely subjected to sexual violence and humiliation.

It’s easy to imagine that the problem only existed in the South in those states that were unwilling to give up slavery. Dennis Childs, an associate professor of African American Literature at the University of California, San Diego and the author of Slaves of the State Black Incarceration from the Chain Gang to the Penitentiary has shown that this is a myth. Childs told me that the absence of an “overt refabrication of slavery” in the North “helps promote the idea that the ‘modern’ penitentiary of the North is progressive, humane, etc.” When we turn to eyewitness reports from elsewhere, however, we find something else. “The writings of prisoners such as Assata Shakur and George Jackson suggest otherwise,” he said. The supposedly progressive northern system treated “Black subjects and other repressed groups” using a “neoslavery” or “concentration camp technique.” It was a system that swallowed, crushed, and spat people out in pieces. Those deemed economically disposable were, thus, disposed of.

Even as the convict-lease system and its northern parallels morphed and grew into the modern penitentiary system, it continued to replicate the mechanics of control perfected during antebellum slavery. Despite legislation restricting the ability of guards to administer corporal punishment, the same tortures administered to enslaved people were visited on the prison population. A 1858 article from Harper’s Weekly that responded to the murder of prisoner Charles Plumb depicted inmates caged and yoked. Prisoners at Sing Sing in New York were suspended by single body parts as a form of punishment.

Though water boarding is no longer practiced in New York State prisons, solitary confinement—a form of torture denounced by the United Nations, Amnesty International and Supreme Court Justices—is more widely practiced in the US than anywhere else. It causes auditory and visual hallucinations, paranoia, PTSD, uncontrollable rage, self-harm and mutilation, diminished impulse control, and distortions of time and perception. These effects are particularly pronounced in young people and those with preexisting mental illness. There is a reason that Angela Davis calls it, apart from death, “the worst form of punishment imaginable.” At the last reckoning in 2005, the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics census revealed that more than 81,622 people are currently held in this condition. The scant data available shows that African Americans are disproportionately represented in the solitary confinement population (even more so than in the prison population in general, which is really saying something). Those suffering from mental illness, who hold what are deemed “radical” political opinions, and trans people are especially likely to wind up in solitary confinement “for their own protection.”

Even though, as Davis has said, slavery is a form of incarceration, incarceration and enslavement are not identical. Convict leasing was not a heritable status and it did not rely upon reproduction for its workforce. But it shared many features with slavery. There’s a reason that W. E. B. DuBois called it the “spawn of slavery” and it is widely known as “neoslavery.” In his book, Childs shows how enslavement and incarceration were closely linked in judicial consciousness and language. In one superficially “colorblind” ruling from 1871, Justice J. Christian declared that “[the felon] has, as a consequence of his crime, not only forfeited his liberty, but all his personal rights except those which the law in its humanity accords to him. He is for the time being the slave of the State. He is civiliter mortuus [civilly dead]; and his estate, if he has any, is administered like that of a dead man.” In the same way the Roman Digest linked incarceration and slavery when it described some condemned prisoners as “slaves of punishment.”

At every juncture in history, the line between enslavement and incarceration is hard to see. The prisoners sentenced to the imperial mines in ancient Italy were often working shoulder to shoulder with enslaved workers. The contemporary habit of shackling imprisoned women during childbirth is a continuation of enslaving practice. This isn’t supposed to happen, but a 2020 report by the Guardian indicates that it is still a widespread problem. This is an area, writes Sarah Haley in No Mercy Here, where it is difficult to demarcate the differences between the enslaving past, the convict yesterday, and the incarcerating present.

It is difficult to claim that these carceral practices are about rehabilitation or protection when the carceral system so clearly harms people. But nothing about this rather obvious argument is new. In 1842 novelist Charles Dickens called solitary confinement “immeasurably worse than any torture of the body” while Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont noted that it was “fatal to the health of criminals” and strikingly ineffective at reforming them. Arguably, ancient Mediterranean people knew this too; in the second century CE the satirist Lucian wrote, “these [prison] conditions were harsh and unbearable for a man who was unaccustomed to those experiences, who had no experience of such a brutal way of life.” So too the ancient novelist Chariton noted that the carceral experience “tramples” the “nobleborn.” What they both understood was that it was possible to train an underclass—in their case enslaved people—to endure the destructive effects of incarceration while simultaneously using that same system to keep them in the trampled state. In other words, they saw it a brutally effective form of social control.

Across history it is striking how inequitable the administration of justice is. In both ancient Rome and the United States (from the end of the Civil war to the present) the affluent face different forms of punishment from the socially disenfranchised. As Larsen put it to me, Roman incarceration “was not necessarily about what was being punished but who was being punished.” Even if we think that depriving people of their freedom, destroying families, causing psychic and physical harm, and forcing people to work for little to no pay is somehow acceptable and just, we surely cannot support a two-tier justice system that punishes people for their skin color, non-Christian religion, sexuality, gender, and lack of economic and social capital.

As numerous activists have noted, the prison system is a place where human rights are handed over with personal belongings. If you think about it, we already knew much of this. Even if we had scrolled past Ava Duvernay’s powerful documentary 13th on our Netflix accounts, jokes like “don’t drop the soap” are evidence that our culture tacitly acknowledges the horrifying sexual violence that exists in the carceral system. And we, for some reason, are okay with that. Removing the exception clause from state legislature is just a first step. Childs told me that the solution is to “ORGANIZE, ORGANIZE, ORGANIZE.” He pointed to groups like Critical Resistance, All of Us or None, and the Youth Justice Coalition as organizations that lead the charge and need support. Until the prison system is reformed, the abolitionist movement is not complete.