When Patrick J. Adams was offered a role in the Broadway revival of Take Me Out, he only knew three basic things about the play. “Gay, baseball, and naked onstage,” he laughs, talking recently via Zoom.

That’s an echo of most people’s knowledge of the show, especially since it opened at the beginning of April to rave reviews… and countless headlines over the sequences in the show that find most of the cast, including Adams and Grey’s Anatomy alum Jesse Williams, dropping their towels for a scene in which the baseball team hits the showers.

The scenes arrive differently now than they did when the original 2002 production won three Tony Awards and cemented Richard Greenberg’s play as a seminal work of theater that discusses gay themes. For starters, audience members are required to lock up their phones in pouches before entering the theater, presumably to thwart déclassé leaks of those scenes.

“I thought, I’m gonna have to be naked? No, I don’t think I can do this play,” Adams says. “And then I read the play and realized it’s about so much more than that. But it is an important piece in the massive puzzle that is the play.”

Adams is best known for playing Mike Ross, the brilliant college dropout who talks his way into a job at a high-powered New York City law firm, for seven seasons on the USA drama series Suits.

It was a memorable TV run for many reasons. It leveled-up Adams’ Hollywood career. He was nominated for a Screen Actors Guild Award for his performance. It was one of the most successful cable series of the last decade and helped define USA’s brand. His character also happened to be written off the show after marrying his coworker Rachel, who was played by Meghan Markle. Adams, who is good friends with Markle, attended the actress’s actual wedding to Prince Harry, a fact that is brought up nearly every time a journalist sits down to talk to him.

But Adams’ run on Suits helped to establish him as a certain brand of actor one could imagine would be everywhere, but requires something so intangible as to render them in short demand, even singular: the intelligent, yet sometimes irascible Everyman. He played the John Cassavetes role in the TV remake of Rosemary’s Baby. There’s something so quintessentially all-American about him that he was cast as John Glenn in the recent series adaptation of The Right Stuff. He’s so downright Hanksian, as in Tom Hanks, that he’ll be the lead in the upcoming Amazon adaptation of A League of Their Own.

Of course, Tom Hanks never stood fully naked in front of 500 strangers night after night in New York City (at least not to our knowledge). But it’s that “type,” and that particular daringness, that made Adams so, well, suited for his role in Take Me Out.

At its most reductive, Greenberg’s play is the fictional story of what happens when the star player of a Major League Baseball team comes out as gay. The emphasis is on fictional as, in 2002, when Greenberg first wrote Take Me Out, there was no out gay player in the MLB. Almost inexplicably, that is still the case 20 years later.

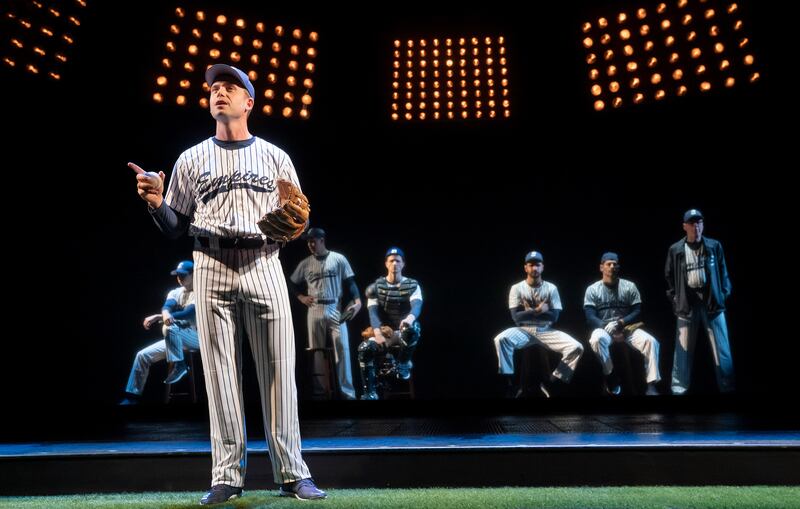

Patrick J. Adams in Take Me Out

Joan MarcusBryan Ruby, who plays for an independent baseball league not affiliated with the MLB, became the only active pro baseball player to be publicly out just last year. Across every other major professional sport in the U.S., the number of out players can be counted on one hand, and is still the seismic, destabilizing cultural event that Take Me Out depicted two decades ago.

But Take Me Out isn’t a “coming-out” play. When Darren Lemming, played by Williams in this revival, announces he’s gay, it’s a catalyst. The production interrogates ideas of masculinity, homophobia, heroism, and guilt, and how, especially now, those things are impossibly tangled. It’s prudent not to spoil what unfolds as the characters try to work through that knot, but narrating it all, speaking directly to the audience, is Adams’ character, Kippy Sunderstrom, the de facto team captain and Lemming’s good friend.

He’s the audience conduit and the avatar for a certain moral idealism, both the preacher of blissful acceptance and the rational instigator of “what it all means.” It’s Kippy who initiates the tough conversations while the cast is fully nude in the locker room shower, who notices the teammates’ discomfort being naked around a gay man and asks them to question what that means about them—what that means about us.

“The nudity was an easy way for me to, without knowing what the play was really about, be like, well, I just don’t want to go down that road,” Adams says. “But then I saw how it was weaved into that beautiful speech in that famous shower scene, where he’s talking about how these guys feel exposed in a way that they never felt before. This sanctuary that used to be their locker room is now changed. Not because Darren came out. It’s our reaction to it, that we no longer can feel the way that we feel because of our own misgivings about what’s going on. ‘We see that we are naked,’ as Kip says. It’s not nakedness just for fun. It’s nakedness to display this really profound point.”

And would you believe that, as opening night approached, baring all in front of a Broadway audience was actually not what scared Adams the most?

Take Me Out is Adams’ Broadway debut. It’s also his first play in six years.

He was last onstage in the 2016 production of The Last Match in San Diego, playing a character that was a lot like Kippy in Take Me Out in that his character talked directly to the audience. During that run was the first time he had suffered stage fright. Not nerves and jitters, but debilitating trauma—a panic attack live onstage.

By that point in his career, he had a lot of theater experience, and nothing like that had ever happened to him before. It took over his entire life during the run of the play: dread and nerves leading up to performances, and then anxiety the entire time he was onstage.

What had been a fun, invigorating aspect of his profession became blanketed with fear. When he was approached about starring in Take Me Out, that fear returned—and was met with empathy. Director Scott Ellis convinced him that it was, in fact, the reason he had to do the show: to get over it.

Now that he’s been performing the show, that fear hasn’t gone away. But years of therapy helped him discover how to get through it.

“I was terrified,” he says. “I had fear onstage. But I had the ability to see it, identify it, and accept it. ‘It’s okay. This is scary.’ Six years ago, I felt the fear and I went, ‘What is this fear? I can’t have this.’ I tried to push it away, and that of course just makes it get worse and worse and worse.”

One would assume that knowing you are going to be naked onstage could make all of that even worse. Or maybe the act is such an ordeal, perhaps even freeing, that the nudity actually helps. “You honestly wouldn’t be wrong,” he says.

Adams felt so exposed and vulnerable the last time he did theater that “whether I was nude or not didn’t matter.” Dealing with his stage fright was such a mountain to climb that the nudity almost became an afterthought, a bridge to cross once he got to the peak. During previews for Take Me Out, he experienced his version of fear and terror at every point of the show… except during the shower scenes.

“I don’t know if it’s because it’s just so crazy, what we’re doing,” he says. But he also suspects it has to do with his connection to the dialogue in that scene, the beauty of the language that convinced him to do the show in the first place. “By that point in the play, I already feel so vulnerable that being naked just feels kind of like, ‘Sure, why not do this too?’”

It would be naive and incorrect to say that, for the audience at each night’s show, the shower scenes aren’t a major experience or a dominating talking point. Sometimes there are gasps. Occasionally there are giggles. At one preview performance, an audience member whistled when the naked cast walked onstage. Adams’ friend reported back to him that, the night he saw the show, someone in the row behind him whispered, “Here we go…” when the shower set arrived.

“It’s titillating and exciting for maybe three seconds. And then it’s like, ‘They’re talking. Maybe we should listen to what they’re saying.’ That seems to be the case.”

In those moments, there are naked men onstage. But, not to be cliché about it, they are baring more than their bodies. It’s the raw instincts, both ugly and beautiful, that they are forced to address because there is literally nothing to mask them.

More than a show about a baseball player coming out as gay, Take Me Out is a play about what it is to be human and to make decisions based on what you think is the right thing to do, and the injustice in how that could still end up causing hurt. Doing the right thing can lead to mistake after mistake after mistake.

That lesson is especially true of Adams’ character Kip, and the role he plays as an audience stand-in. No matter how much you truly believe that speaking the truth will make for an easier path forward, or kickstart a journey toward the utopia you think the world—or at least the corner of the world you occupy—could be, that doesn’t mean that will be the case. Your certainty doesn’t absolve other people’s unknown. Their fear. Their reluctance. Their unpredictability—or, maybe, their utter predictability, the fact that the power of the truth may not be strong enough to knock down the walls, rules, and biases fortified over generations.

Kip doesn’t understand that. That he’s so well-meaning and so optimistic is his fatal flaw—perhaps even destructive. It’s telling that Richard Greenberg has said that he wrote this play in a hurry in 2002 because he felt that there’s no way it could still be relevant even just years from then. Surely, the idea of a sports figure coming out of the closet would quickly seem dated. Twenty years later, the play is being revived and the conversation surrounding it is marveling—often in dismay—over how relevant it still is.

Adams isn’t a professional athlete. He laughs at himself when he calls his character’s baseball uniform a “jersey.” The Canadian-born actor is more of a hockey guy. “Do you even call it a jersey in baseball? I’m revealing just how much I know about baseball now…”

But he is in an industry that serves people’s private lives up for public consumption, and, with that, judgment. His marriage has been covered in celebrity magazines. (He has two children with actress Troian Bellisario.) His good friend might have the most picked-apart personal life in the world. Might that have given him a different angle into the themes of the show? What it might be like to be a public figure, or the friend and colleague of a public figure, who has to weigh the decision to come out as gay because of how it might affect their career and the treatment they might receive from hateful people?

“It’s so hard for me to talk about because I wouldn’t ever want to pretend like I understand what it’s like to have to make that decision,” he says. “Even in Hollywood, we think of ourselves as very woke and open and receptive to all, but it’s still probably very similar behind closed doors.”

Patrick J. Adams as Mike Ross, Meghan Markle as Rachel Zane on Suits

Robert Ascroft/USA Network/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images“I would hope with a play like ours, even though it’s about a very insular situation with a baseball team, that people could come to it and see it play out in any industry. We all think we are so understanding. Especially now that we’re all having the harder discussions, we all want to pat ourselves on the back for having them. We think we’ve come so far. But how far have we come? How easily could that be tested?”

Adams has been working on screen for the last 20 years, and certainly at a higher level of fame and recognition since the success of Suits. The being a celebrity of it all, the being in a public relationship of it all, the being a friend of Meghan Markle of it all and having people constantly ask about it… “I’m just not very good at it,” he says. “That’s what I've learned over the years.”

Especially now that he has two kids, he finds himself alternating between retreating from the necessary evils of social media and press tours entirely, and dipping his toe back into it, like he is now, because, frankly, brand management is an essential part of the business. There are actors who are good at navigating it, who have figured out a way to actually enjoy both the craft and curation parts of the job.

But it’s hard to fathom that when there are instances, as has happened a handful of times, that a celebrity gossip reporter with a recorder starts snickering while asking how he’d feel if Meghan Markle came to Take Me Out and saw him naked.

“And I always fall into the trap of answering it, and then it always gets published in a way that makes it seem titillating,” he says. It’s an impossible position. “I don’t want to talk. But I also don’t want to pretend like it doesn’t exist, either.”

But, like almost everything to do with this Take Me Out experience, even that has been a pleasant surprise. For the most part, juvenile reactions, whether to the nudity or to his famous friendships, have been few and far between. “I think people have understood that what we’re doing here is more than that, and those questions don’t really resonate with what’s going on.”

It’s not about being naked. It’s about the naked truth.