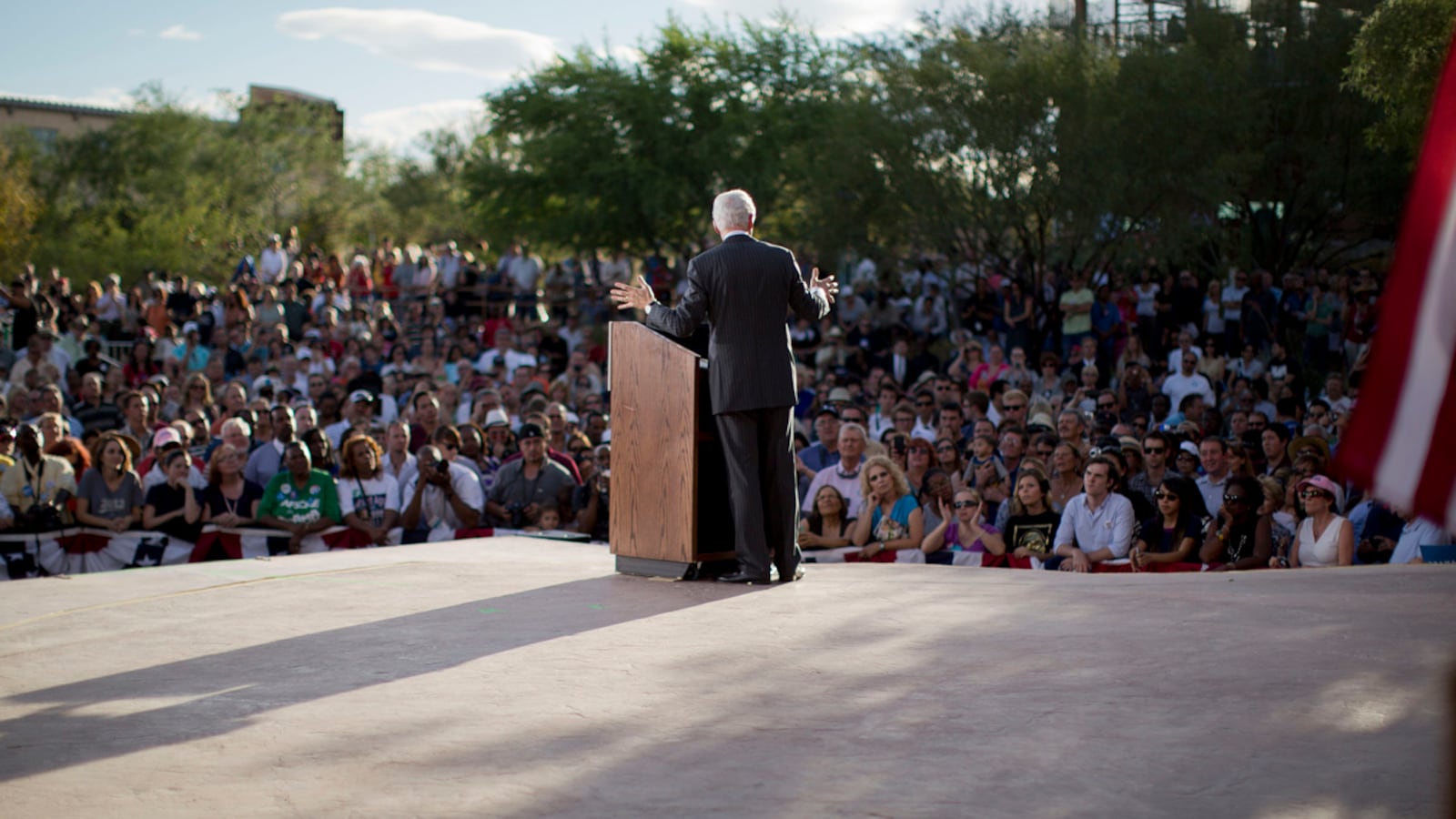

Even after 21 years I marvel. The deep, personal connection he is able to make with an audience. The ability to attack without demonizing. The capacity to explain the most complex ideas in plain talk. The commitment to treating people like intelligent adults, capable of making the right decision after hearing all the facts. And the integration—his greatest intellectual skill—the ability to learn and retain billions of bits of information and synthesize them into a coherent worldview.

I once asked Democratic mandarin Bob Strauss—who knew both Bill Clinton and Ronald Reagan well—what their secret was. Trying to quantify charisma, Strauss said, “is like trying to nail Jello to the wall.”

Developmental psychologists tell us that the way we learn as infants is interactional synchrony: mother smiles at her infant and the baby smiles back. Monkey see, monkey do. It's the same with a politician. You get back what you give out. People love seeing Bill Clinton because he loves seeing them. They have fun because he's having fun.

His gestures are part of it, too. Sure, he does the thumb-jab—a must for every politician who's been taught it's rude to point. But most of his gestures are sweeping—reaching out, opening up, drawing you in. Those oversized hands come to you, then return to his chest—he reaches for your heart, and holds it close to his.

He never calls them speeches. Talks. They are talks. He has an aversion to overblown rhetoric and theatrical puffery. When you're worried, or in pain, he says these days, you don't want eloquence; you want explanation. When he was in the hospital with a bad ticker, he notes, the poems and prayers meant a lot. But you fight fear with facts—a caring, competent doc with a good bedside manner and a plan to save your life is far more comforting than sweet-sounding words. He prefers a conversation, and conversations aren't etched in stone, they're iterative.

It is the interaction that is essential. He's never been as magical alone with a camera as Reagan. In fact, at the beginning of his presidency his Saturday radio addresses were flat—until we began bringing folks into the Oval Office for the taping. I brought my parents when they were in town, my kids, my priest, whoever was available. Everyone was treated with the same deep interest and curiosity as a prime minister.

During the exhausting 1992 campaign I was asked if Clinton got tired of the crowds: their neediness, their wide-eyed lunging. No way, I said. It was like force-feeding sugar to an ant: you just can't overdo it.

One night the crowd in the border town of McAllen, Texas, was so excited Clinton nearly got carried away—literally. Leaning over the rope line to shake hands three and four people deep, Clinton was lifted off his feet and almost began crowd surfing (and he was a heavier man in those days). His Secret Service agent grabbed the back of his belt and forcibly yanked him back to earth. For an instant Clinton wheeled around and glared, astonished that someone would break the magic of the moment.

He's had a lot of nicknames. These days some folks refer to him as the Big Dog. As president his code name was Eagle. But back in his first presidential campaign it was Elvis, and to me he is still the King.