Roughly three hundred years ago residents of the Polish village of Pien refused to take any risks. When they interred the remains of a wealthy woman in the local cemetery, they were concerned that she wouldn’t stay put. So, they did what any of us would do and installed a security system. First, they shackled her foot to the grave. Then, they put a sickle around her neck so that she would be decapitated if she attempted to rise from the grave. If it wasn’t clear already, the currently unidentified woman was suspected of being a vampire.

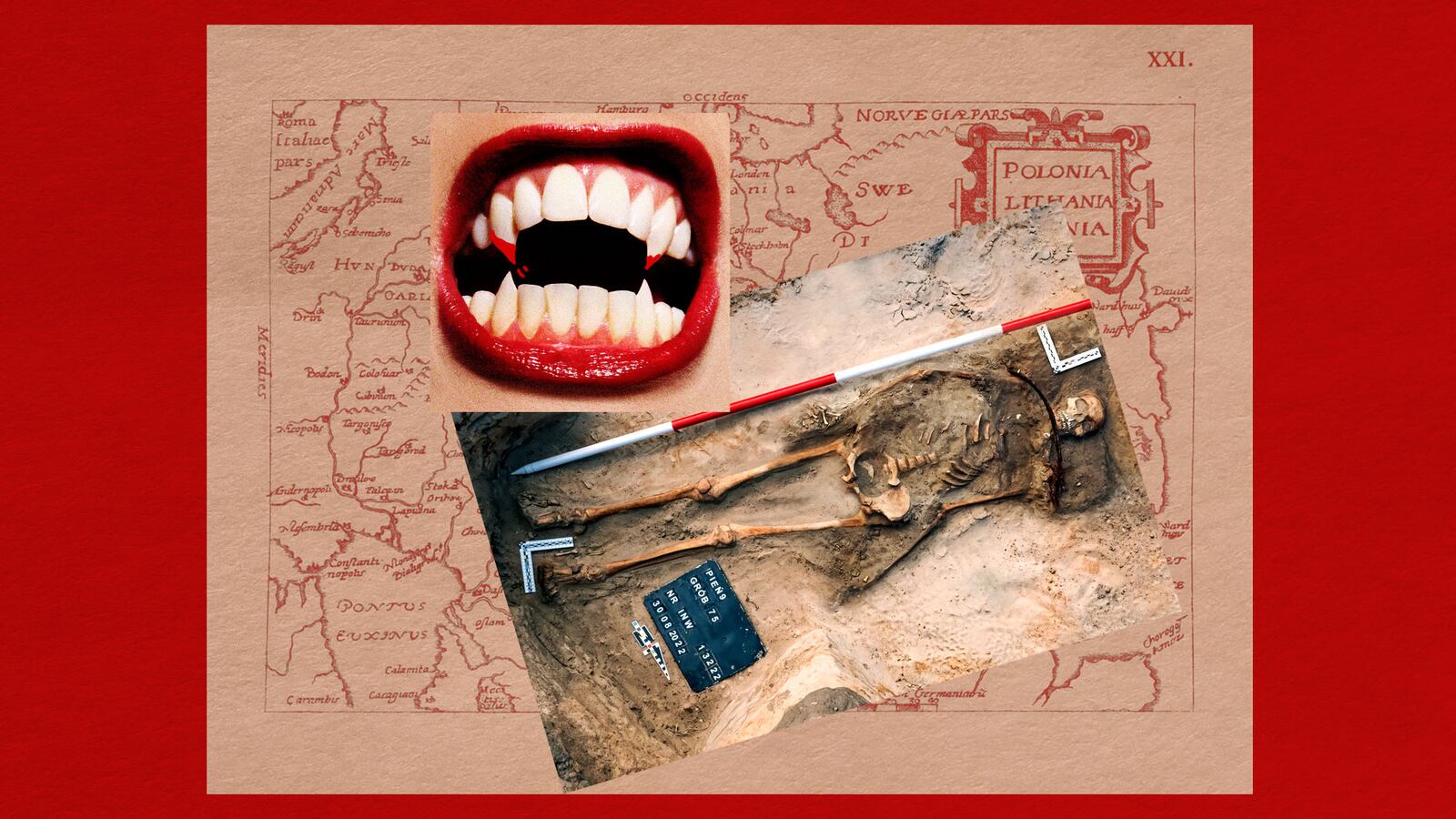

Archeologists from Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Poland unearthed the woman’s remains while excavating in the cemetery of the southern village. The woman’s burial, the scientists say, reflects the elaborate rituals associated with the treatment of potential vampires. These rituals were about disorienting or constraining the dead using symbolic and physical restraints.

Dariusz Poliński, a Copernicus professor and leader of the excavations, said that the practical physical strategies for protecting oneself “against the return of the dead [included] cutting off the head or legs, placing the deceased face down to bite into the ground, burning them, and smashing them with a stone.” In the same way, said Poliński, “The sickle [placed around the neck] was not laid flat but placed on the neck in such a way that if the deceased had tried to get up most likely the head would have been cut off or injured.” In other words, the graves were booby trapped. The padlock on the woman’s big toe, on the other hand, served a more symbolic function: it represented “the closing of a stage and the impossibility of returning.”

As noted by Sarah Cascone, this is not the first discovery of its kind. In 2014 academics excavating and reporting on five sets of remains from Drewsko (roughly 130 miles from Pien) described finding sickles pressed to the throats of the deceased in order to prevent their nocturnal meanderings. In the case of these individuals, they appeared to be immigrants to the region. In the case of the Pien woman, the fragments of a silk cap in her tomb suggest that she was of high status. This can explain why it is that she was buried on holy ground rather than in a mass grave.

Archeological evidence of apotropaic burial rituals to protect the living from the dead is not limited to Poland. Other examples include a first century CE 10-year-old child from Lugano, Italy, who died of malaria and was buried with a rock in her mouth; a forty-something Bulgarian man, who was staked in his grave in the thirteenth century; and a Venetian woman who was buried with a brick in her mouth to prevent her feeding on plague victims in the sixteenth century. Vampires appear cross-culturally and burial rituals to prevent them from rejoining the living are also not constrained to a single time period or country. But they did seem to come to a head during the Great Vampire Epidemic of the 18th century, when people from Eastern and (later) Western Europe believed that vampires were appearing in large numbers throughout the continent. A similar epidemic of suspicion arose a century later in New England and is tied to the spread of tuberculosis.

Lesley Gregoricka, who authored a study on the Polish examples from Drewsko, linked belief in vampires to the spread of disease. She cited schizophrenia, cholera, tuberculosis, and rabies as diseases that were interpreted as signs of vampirism. As University of Virginia Slavic languages professor Stanley Stepanic has described, the vampire was “a symbol of disease in original folklore.” When many were dying of seemingly inexplicable conditions, those who flourished or were seen as outsiders were eyed with suspicion. The vampiric epithet “nosferatu” actually means “bringer of plague.”

The link between vampirism and illness passed into the literary history of vampirism as well. Contrary to what many people think, the first vampire novel was not Dracula but Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1872 homoerotic short story Carmilla. This story describes the relationship between a frail young girl and the mysterious aristocratic stranger taken in by her family. Written twenty-five years before Dracula, Le Fanu’s story is an homage to concealed desires and identity. Not only is the exquisite Carmilla an ancient vampire named Miracalla, but her dear friendship with Laura only barely covers her romantic longing for the girl. But as Carmilla grows stronger Laura only grows weaker. The same phenomenon appeared in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Here, Lucy wastes away from a mysterious illness caused by Dracula nocturnal feeding. The best indicator that you have a vampire or succubus on your hands is when someone in your household grow sick.

Vampirism can articulate and probe a variety of different societal fears and questions from race relations to gender identity, to homosexuality, and religious mythology. One thread running through its description is the ways in which vampirism is a form of parasitic exploitation. Often this exploitation harnesses gender stereotypes of class conflicts. According to legend, the sixteenth-century Hungarian Countess Elizabeth Bathor de Ecsed, the vampiric serial killer more commonly known as the “Blood Countess,” bathed in the blood of virgins in order to preserve her youth and beauty. The Countess’s story, alluded to in modern horror movies like Hostel 2 (2007), embodies a principle that is at once ancient and modern: the idea that blood contains a power that preserves health, youth, and beauty. Ancient medics claimed that the blood of gladiators and virgins had special medicinal properties, but modern medicine operates with the same assumptions. Billionaires like Peter Thiel also attempt to use the blood of the young to increase their longevity. Given her presumed wealth perhaps the woman was viewed in this light.

In the case of the woman from Pien, however, her specific case and identification as a vampire may have been less about epidemiology than it was about dentistry. The woman had a protruding front tooth, which some have suggested led her neighbors to suspect her. Given early modern standards of dentistry it’s not clear how problematic her tooth would have been to people. But her postmortem mistreatment certainly offers a compelling reason to get braces.