Editor’s note: This is an amended version of a review that originally appeared on the opening night of the off-Broadway production of the show at the Public Theater.

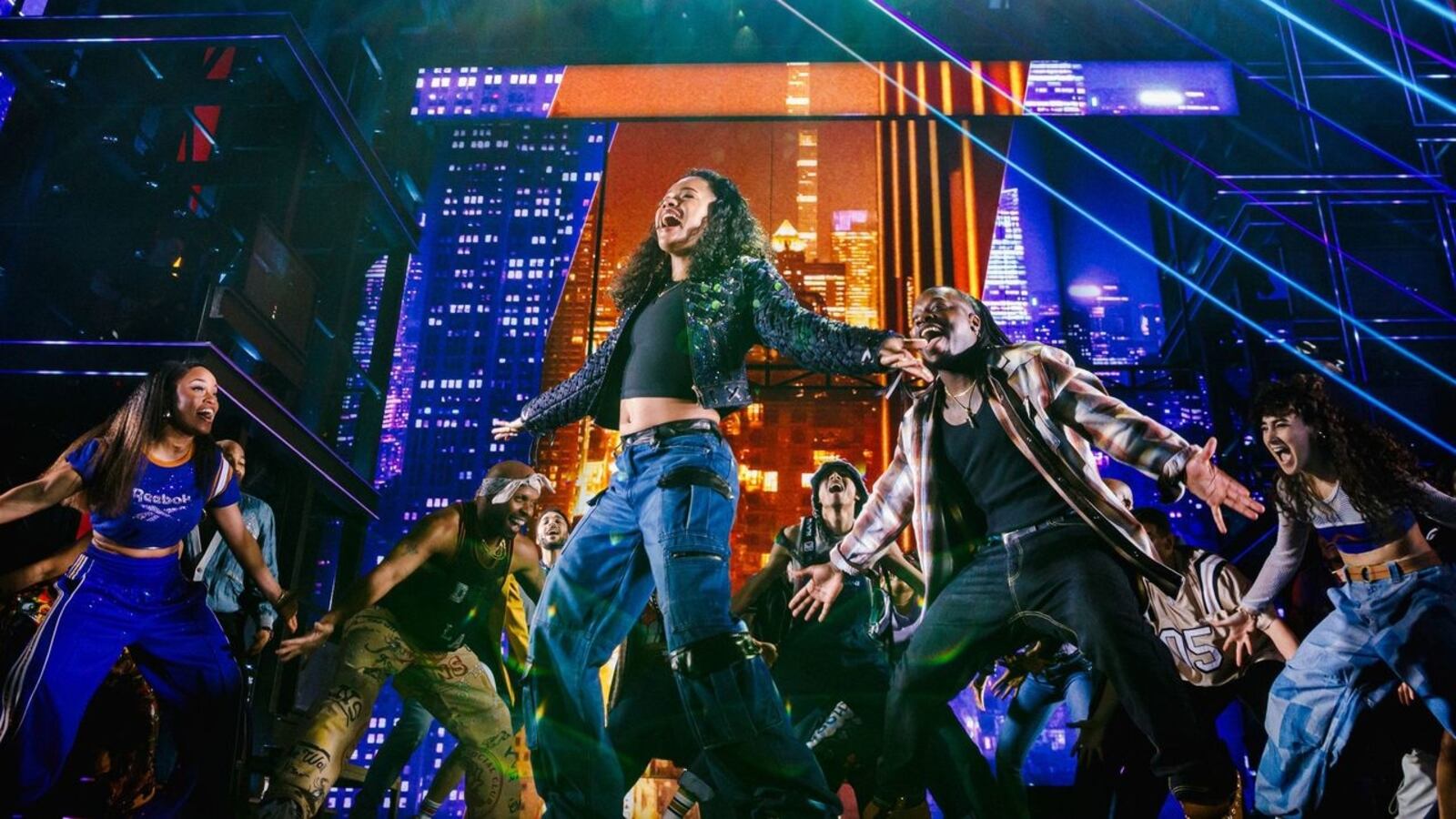

Hell’s Kitchen, Alicia Keys’ part-autobiographical musical, has finally found the right stage to explode on. In its off-Broadway incarnation at the Public Theater, it felt modest and a little plodding. Now, at the Sam S. Shubert Theatre (booking to Sept. 29), it feels properly, impressively amped up. The story remains lackluster, but who cares when the music and dancing are so gorgeous, propulsive, and electrically alive and vivid.

The production, directed by Michael Greif, has a through-line of sweetness that overrides a roughness of New York City living it implies but never delivers on—and spiritually never wants to dwell in. Its mean streets are not that mean, its central romantic storyline never rises to a passion that the audience feels invested in, and its family dramas are of the safe, after-school special kind. This is, at its heart, a warm bath of a musical; Keys’ music now has a massive space to happily fill, while Camille A. Brown’s fabulous choreography supplies a welcome and impressive swagger.

Book writer Kristoffer Diaz told WNYC that Keys “did not want to do a biopic, the retrospective of an amazing artist, because she’s in the middle of her career. She’s still making hit after hit after hit. So we wanted to focus on a really specific small moment in her life. I think we did that.”

Hell’s Kitchen is a tender and quiet love letter to a city, as well as a coming-of-age tale; its warm-hearted core, rambling script, and an indulgently overlong run-time are undercut with smart one-liners and peppily wry performances. The setting is some time in Rudy Giuliani’s ’90s mayoralty-of-New-York-City era: 17-year-old Ali (an excellent and engaging Maleah Joi Moon) lives with her white mom Jersey (Shoshana Bean, loving, tough, fiercely protective) in a one-bedroom apartment on the 42nd floor of Manhattan Plaza, the Midtown West building famously then-as-now heavily populated by those working in the arts.

Jersey keeps a rigorous schedule focused on her daughter’s care; as Ali has it, “dinner every night between 6 and 6:30 before she leaves for work. The night shift. Her second job. In bed by 9.” Her dad Davis (Brandon Victor Dixon, charming, gently-not-really roguish) is absent, then suddenly present again. Ali is annoyed that Jersey doesn’t give her enough freedom; trouble at home brews after she falls for Knuck (Chris Lee), a guy in his twenties who with his friends plays drums outside Manhattan Plaza.

Knuck knows exactly how people mistakenly see him as a ne’er-do-well. In reality, he’s a hard-working, community-focused young man who just wants to get on. Jersey sees him as a gateway to Ali wasting her entire life, and so the tension of the musical is born, culminating in one of the most puzzlingly staged non-riots this critic has ever seen on stage.

You don’t feel as if you’re in or around Hell’s Kitchen. Manhattan Plaza is its own unique community and social ecosystem, and the streets—once Ali is out on them—aren’t as specifically rendered as the title of the show suggests. Indeed, she spends most of her time heading east to Gramercy Park or the Lower East Side to see Knuck. You keep waiting for the Hell’s Kitchen-ness of the title to assert or distinguish itself, but it does not.

Shoshana Bean, left, and Maleah Joi Moon in 'Hell's Kitchen.'

Marc J. FranklinThe show also has a habit of neutralizing all points of contention; it will set up a conflict, then have everyone quickly get along, or see their errors or understand their failings, because everyone is basically understanding. Knuck is an extremely responsible, quiet guy who is mortified to learn Ali is younger than she had led him to believe; their relationship never really takes flight, and they have a most mature separation.

Davis is a non-malevolently absent parent, so when Jersey reads him the riot act, it is deserved, but he knows it, and it is forgiven by the final number. Jessica (Jackie Leon) and Tiny (Vanessa Ferguson), Ali’s friends, seem potentially interesting, spiky commentators on the action, and should have more to do.

Keys’ new and very familiar compositions all sound great (arrangements are by Keys and Tom Kitt; orchestrations are by Adam Blackstone and Tom Kitt), and the choreography is so distinctive and brilliantly executed by an exceptional company of dancers that it sharpens and enlivens any scene in which it features.

Robert Brill’s scenic design is a modular, multi-level affair to convey the high-rises and crowded streets as simply as possible; Dede Ayite’s costume design is NYC-perfect; Natasha Katz’s lighting and Peter Nigrini’s projections add extra city scale and feel. gain, all feel so much better suited to a big Broadway house than the Public.

Ali keeps expressing her frustration, but one has to ask—with a lovely mom (who’s not even that strict), and people looking out for her, like Ray, a dream doorman played by Chad Carstarphen—why is she so pissed off? She’s intelligent and musically gifted, her perils and troubles are pretty minor, and Hell’s Kitchen doesn’t quite know how to make her repetitive complaining consequential.

When she says of her mom, “She sees me having even a little bit of fun—a little bit of a life—and right away, there she is. It’s just me, locked away in this tower, cut off from this city that’s honestly the only place I want to be,” you want to say: come on Ali, from what we can see on stage, you have it pretty great!

Kecia Lewis, left, and Maleah Joi Moon in 'Hell's Kitchen.'

Marc J. FranklinThe presence of Kecia Lewis’ Miss Liza Jane as a regal piano teacher hiding a secret pain of her own is the dry corrective to all the overstated angst on stage— “You are here because the voices of your ancestors have requested your presence. Sit. Learn,” she tells Ali. And it is Lewis’ singing—particularly with the guttural and soaring “Perfect Way to Die”—that will leave you the most open-mouthed and moist-eyed.

The musical doesn’t drill into big issues hovering at its margins (race, policing, class, betrayal, sex, love), and at all times underlines the themes of personal responsibility and care all its characters hold dear, and—if they fall short in exhibiting these qualities at different moments—looks, glances, and words soon convey that all necessary, proper and right lessons have been learned. Hell’s Kitchen is extremely wholesome.

For example, Ali’s mom soon regrets her hot-headed behavior towards Knuck, and is soon telling her daughter to make sure he is OK after his non-arrest after the non-riot, which she feels responsible for. “The hell was I thinking? I could have gotten him killed… There’s no excuse. For any of it.” Thankfully, Bean’s maternal spikiness as Jersey remains. She tells Ali to go be with Knuck, but as her daughter heads towards the door, adds sharply, “Tomorrow. Sleep here tonight, go see him tomorrow. Do not sleep with him! Please.”

If the drama is kept on an unthreatening simmer throughout, an Alicia Keys musical set in New York can only end one way, and so it is with Hell’s Kitchen—which nails its “Empire State of Mind” finale with all the stage-filled, hometown razzmatazz you’d anticipate and hope for. On Broadway, you have no choice but to leap from your seats.