It was strange for Richard White to see the fountain again, he said. As a 3-year-old boy, he was homeless and the fountain, in a park in the West Baltimore neighborhood of Sandtown-Winchester, was where he would drink and also wash himself. He would have to strain every muscle to make the fountain operate. Now, as a 6-foot-plus adult, he dwarfs the same fountain, he said, his warm, deep voice vibrating to a soft chuckle.

White’s life has seen him move from being a homeless young boy, adopted when he was 4 by the same couple who had once adopted his mother, Cheryl, to becoming one of the most celebrated African-American artists in the very white world of classical music.

White is the first African-American to receive a doctorate of music in tuba performance. He held the position of Principal Tubist with the New Mexico Symphony from 2004 until its demise in 2011. He has played with numerous orchestras, traveled the world as a player, and is currently in his fifth season as principal tubist of the New Mexico Philharmonic, as well as teaching at the University of New Mexico, where he is Associate Professor of Tuba/Euphonium.

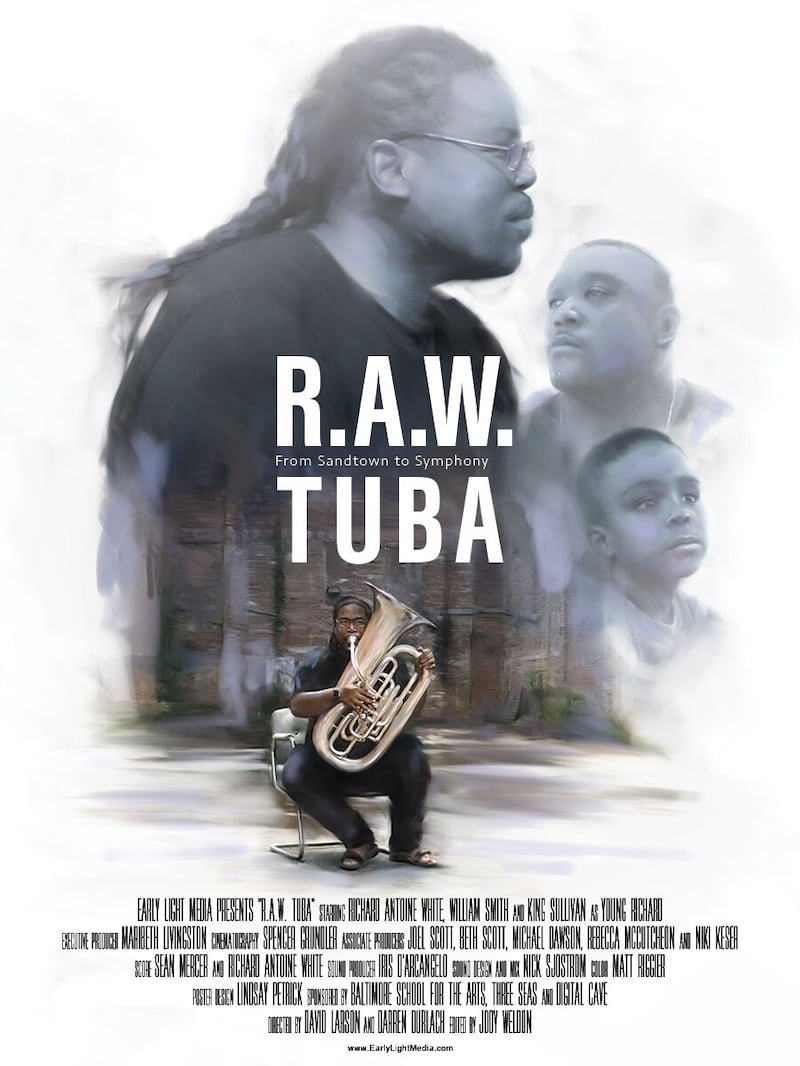

White is also known as ‘RawTuba’ (R.A.W. stands for his full name, Richard Antoine White). A documentary about his life, directed by Darren Durlach and David Larson and which will be screened for the first time in Baltimore on Feb. 8, has the title R.A.W. Tuba.

Richard and his mother were both adopted (at different times of their lives) by Vivian and Richard McClain, and so it was that his grandparents became his parents, he said.

When White considers the sweep of his life, “I think how many of ‘me’ have we missed in every city in America because they didn’t receive the proper amount of help,” he said. “We have this mis-illusion of, if we help someone and they don’t achieve, then they’re no good or lazy. But we are built with different strengths and abilities.

“I only needed level 1 or 2 help, someone else may need 3 or 4. Not one size fits all. I was very lucky. I got the help and guidance I needed, and people were kind. There are thousands of me all over the world. If we actually follow through with action to help them we may have 100 Winston Churchills, 100 Martin Luther Kings. I think we’re letting a lot of talented, inspirational people through the cracks and not nurturing them enough.”

Had White not been helped, he said, “I would have got addicted to some drug or be dead, there’s no doubt in my mind. I was blessed with determination. I don’t know if it’s anger or what, I’m like a bulldozer. I keep moving forward. It was a gift I was born with.”

It was odd to film the documentary and be recognized by someone from many years previously. “That’s why I need to talk to someone. What does it mean? If it means nothing, I have to have the realization that it means nothing. I feel I’ve been dealt with a shitty hand. I’ve faced obstacles no one should have to face, but I hope my life shows how to rise above it and see good in it.”

White paused, and said slowly and with emphasis, “People talk about, and break down, the American Dream. I have lived it.”

His mother became pregnant with him at 16 and gave birth to him when she was 17, White said. Her parents were strict, leading to tension and her leaving home and living on the streets. “She battled alcoholism,” said White. “I was born premature. I weighed just over a pound. You could put me in your hand and close it.”

For the first nearly four years of his life he lived with his mother on the streets of Sandtown (“Freddie Gray's neighborhood,” as White called it), finding rooms in empty houses, and sleeping on random couches. White recalled days spent trying to find Cheryl or supporting her to stay upright while she was drunk. “I would roam the streets in dirty clothes. I would find coins in the gutters. I would buy chicken gizzards, five for a dollar.”

Sometimes White would store morsels of food under his tongue because he wasn’t sure when he would eat again: “I didn’t really know the importance of three meals a day.” He would often be barefoot, and the shoes he found rarely fit so he would stuff newspaper in them.

He recalled the abandoned houses with boarded-up windows that he would crawl into, the scars on his knee from falling through floors. “All I wanted was to be with my mom,” he said.

The block seems smaller today, the water fountain in the park he would drink from and shower in, small, as opposed to the huge contraption he tried to scale every day. “I probably smelled horrendous. I always had a snot nose.”

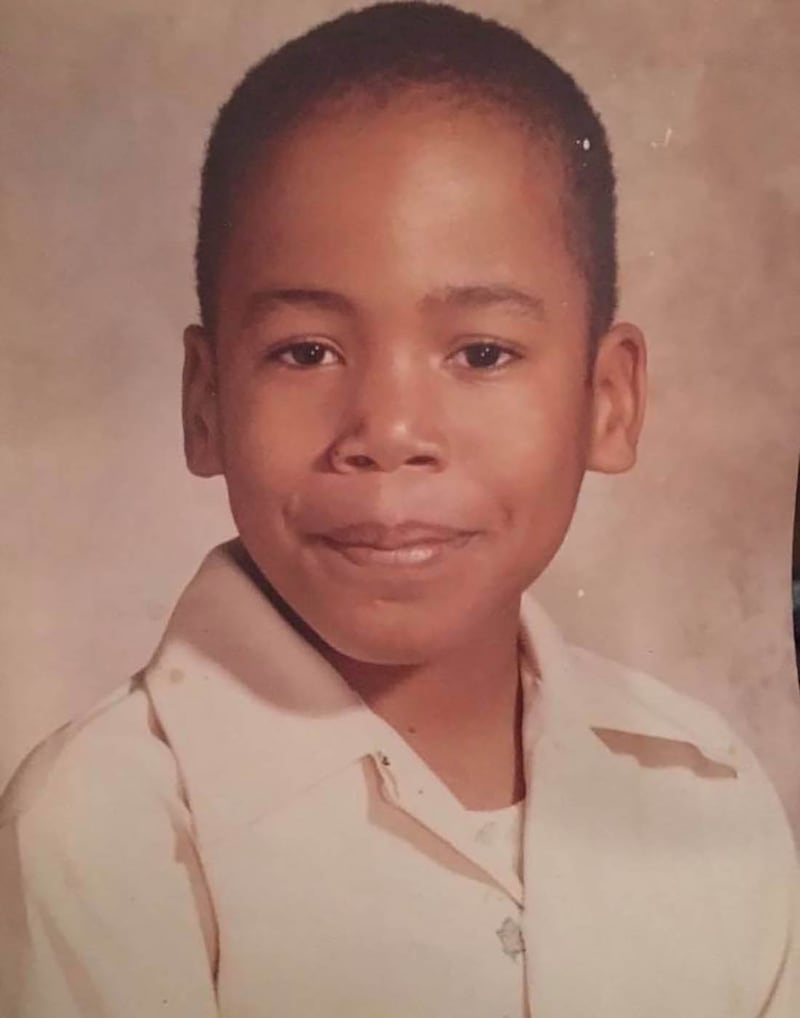

White: "This is from cross country elementary school, grades 1-5. If I had to guess, 1st or second grade."

Courtesy Richard WhiteHis biological father, Raymond Tyler, “got caught up in something illegal.” White recalled seeing him once through the glass window of a prison meeting room. Five weeks ago, he spoke to his father by phone for the second time in his life. His father is now out of jail. “I am sad and grateful,” said White. “It was overwhelming emotionally. I’m at capacity right now. We’ll have to talk more later. I am excited, but I also don’t know how to process it. He wants to mend our relationship.”

Raymond told White he had a sister, Tyra, he had never known about, who had just died after a horrific car accident. “I didn’t know her. How am I supposed to feel about this?” White asked.

His relationship with his half-brother, William Maurice Smith, was awkward for years. The two are now close.

White is thinking about how his relationship with Raymond can progress. “I would like to get know him, but I’m 45 years old. My life is what it is. My dad is the person that raised me.” Since making the film, he has heard people tell him how much they love him, they remember him from being a little boy. He doesn’t know who they are.

It’s odd to hear people tell him they love him today, when his memories are of knocking on people’s doors and being turned away and told to find his mother.

“America has inner-city problems,” said White. “Me sleeping under a tree didn’t bother anyone because people were fighting their own demons, like alcohol or drug addiction and abuse.”

As a young boy, he would be carrying trash bags filled with his possessions from one place to the next, to church basements to get clothes. He knew that he was living a life different than other children, “but not enough to complain about it. I wasn’t old enough to do that. I remember I always wished for a brother. In my mind I thought if I had someone else to hang out with, or if I could find my mother, things would be easier.”

Family members tell him now that they had extra food to share, but that White’s mother didn’t want anyone else taking care of him except her, and that White himself didn’t want to be anywhere else except with her. Somehow no one, and no agency, intervened until White was 4. “Everyone knew my mother had alcohol problems. I would get smacked around. No one took any responsibility for me. Until the day I was found freezing cold in a vestibule, no one acted on it.”

It was January 1977, and there had been a massive snowstorm in Baltimore, White recalled. He, then just 3 years old, couldn’t find his mother. He had gone to the tree under which they used to sleep, and she wasn’t there. Exhausted and cold, he slept in the entryway of a derelict house.

“I woke up in a bed with covers and hot tea, and lots of adults and authorities. I don’t remember the name of those people,” he said. “I went with Vivian and Richard McClain, and afterwards to their house. Soon after my mom eventually came to their house and retrieved me. But the social workers and Vivian and Richard were aware of this fragile situation.”

White spent a short time with his mom, “and then another incident of me not being able to find her happened, some calls were made, and my dad (Richard McClain Sr.) came to get me and I was with them ever since.” Richard finally moved in with Richard and Vivian in May 1977, as he turned 4, with the McClains eventually obtaining full legal custody of him.

Acclimating to not being on the streets was tough. For the first few days it felt odd sleeping in a bed, so White slept on his new bedroom’s floor. He wasn’t used to eating three meals a day, and would keep sandwiches in his pocket in case they would be his only food for the day.

He and Richard Sr. are very close, he said, but not overly affectionate. Making the movie, Richard Jr. would say, “Dad, I love you.” His father would reply, “OK, that’s good.”

Richard McClain told The Daily Beast that he was “extremely proud,” of his son, and that his son’s determination had seen him succeed. He was as humble as Richard Jr. had indicated he would be about his and Vivian’s own vital roles in helping Richard Jr.

Angie McClain, Richard and Vivian’s daughter, said she had helped bring Richard up. “He learned how to be respectful here. I saw his drive and determination. We’re so proud.” Richard Sr. has seen Richard Jr. in concert at Johns Hopkins University. “My mom (Vivian) would be jumping for joy,” said Angie.

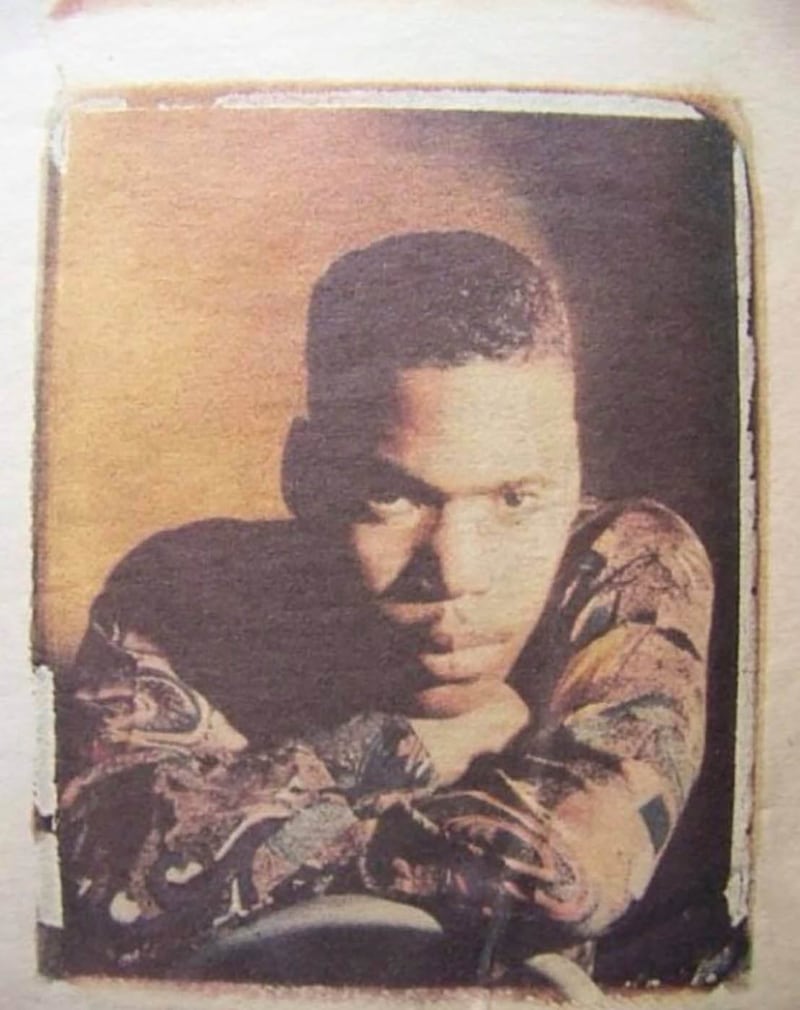

White, in his senior year of high school

Courtesy Richard WhiteWhite’s adopted parents had brought Cheryl up, and so, when they gained legal custody of Richard Jr., they cautioned her against making promises to her son that she couldn’t keep.

“They cut the cord,” said White. “For years, I thought these people had taken me away from my mom. I didn’t see at the time they were giving me the chance for a better life. Back then, I did as much as I could not to talk to them. I talked to myself in the mirror for years.”

“I bought him a trumpet. His teacher took the trumpet from him and gave him a tuba, and he never stopped with it,” said Richard Sr.

His schoolwork had been going poorly in 4th grade and Richard and Vivian threatened him with taking the trumpet away unless his schoolwork improved, “and I didn’t have a failing year at school since,” White said.

Before music became his life, Richard wanted to be a footballer. He was 6-foot-5 and 300 pounds. “I was built to play football, man,” he laughed. “If I could have played football rather than the tuba I would have done without hesitation.”

The plan, he said, had been to attend a vocational technical school, be a carpenter, and play football, but, aged 15, after “a horrible football injury,” he was told that if he suffered another injury he wouldn’t walk again. Music became the most important thing to him.

“My drive in life is that I don’t think I’m better than anyone, but I think I can be as good as anyone else,” White said. “When someone says I can’t do something, it’s the best motivation. I don’t care if I have to do something a trillion times, I will do it. Sometimes I do things the hardest, rather than easiest, way.”

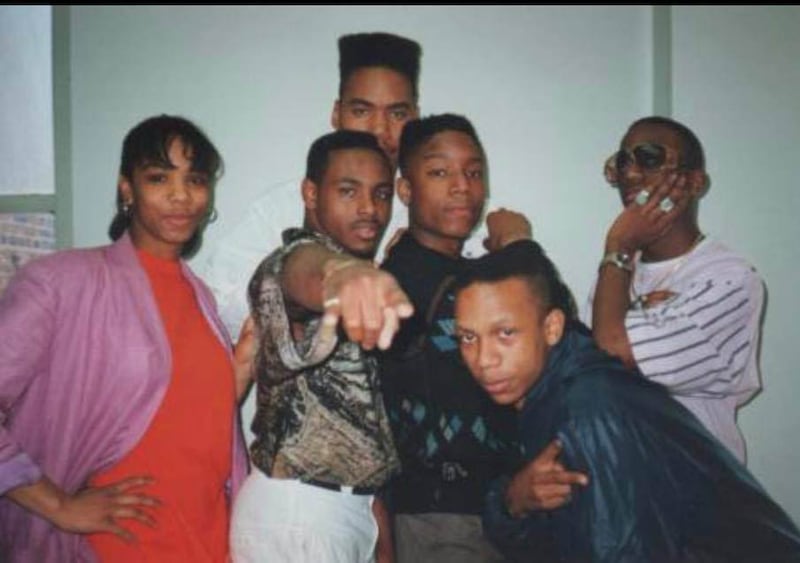

White: "Definitely Baltimore School for the Arts 10th or 11th grade. Me in the back Kid N Play high top fade! Mix of music and theatre majors in this picture."

Courtesy Richard WhiteWhen he would go to the local basketball courts, he said, the drug dealers would make him go home. “They knew I had something going on.”

In 10th grade, Richard and Vivian asked White if he would like to call them mom and dad rather than grandma and grand-dad, a significant moment for them all.

His mother saw an article about him in the Baltimore Sun as a promising young musician in his senior year at high school, and then—after being rushed to hospital after an asthma attack—the last thing she said to William before she died was, “I want you to be like your brother.”

Cheryl died, aged 36, in June 1992.

William says their mother was a “phenomenal woman with demons in her life.” She would be proud of Richard, he said. “She’s up there doing jumping jacks right now.”

At the Baltimore School For the Arts, when the professors corrected his grammar, White initially thought they were “trying to make me white, rather than cultured. I didn’t want to talk like white people, I’m from the streets. I wore sweat pants. It was awkward to fit in. If I hung out with my street homies, I sounded weird. They asked why I was talking funny. The gap between being educated and them not caused friction.”

The School For the Arts (out of 600 applicants 35 are accepted every year) saw a talent in White, and his teachers—particularly Chris Ford, now the BSA’s director—believed in him, and insisted he work hard and focus. At the time, White said, he didn’t know why he wasn’t kicked out.

White laughed, recalling meeting Ford for the first time, and reading music for the first time having learned to play the tuba by listening to tapes. He laughed again, recalling that he thought he could make money by playing the tuba.

He was at school at 7 a.m. every day, he practiced all the time, including through lunch. His contemporaries there included jazz trumpeter Dontae Winslow, Jada Pinkett Smith, and Tupac Shakur. “I never heard anyone speak so eloquently and so ghetto at the same time,” White said of the latter. “He pushed me to understand that if someone calls you basic it’s not a compliment.”

White was particularly inspired by Harvey Phillips, distinguished professor emeritus at the next educational institution he attended, the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music. At Phillips’ ranch White helped to bail hay and paint fences. “He instilled into me what it is to be a good person, and told me that if I wanted to be successful to think of something that was needed but didn’t yet exist, and do it.”

None of his teachers gave White a pass, White said. “I learned that hard work is not bullshit. It was like, ‘Work hard, fail, work harder, fail, work harder.’ The secret to success is to work hard, work harder, and work as hard as you can. I have no choice but to do it. For some reason my teachers didn’t give up on me. I don’t know why.

“I’m sad when I think that I might die before I get to do all the things I want to do. It might be true for everyone, but I don’t care how long a thing takes. The only thing that can stop me is death. I had the same mentality growing up. Those that have to make it will make it. I don’t have a choice except to keep trying. The only thing to stop me from trying is when I can’t try any more.”

White laughed gently, recalling that his singular achievement in tuba may be down to an African-American boy who yanked on his coat one day on the Baltimore subway, while he was complaining to Richard Sr. about finishing his degree.

“Hey mister, you got a doctorate?” the little boy said. “Oh man, I’ve got to finish it now,” White thought. “That changed the course of my life. If that hadn’t happened I probably wouldn’t have finished. It motivated me to carry on. I knew why I had to do this. When I got to Peabody (Conservatory of Music), I was one of only two black people there.”

There, his teacher was David Fedderly, who held the Principal Tuba position with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra from 1983 to 2014, who pushed White as hard as Chris Ford had at the Baltimore School For the Arts.

Only 1.8 percent of U.S. symphony members are African-American. When he was at Peabody, White met with the then-Dean to mull ways to make the institution more diverse and accepting, “because it was weird walking around and not seeing anyone who looks like me. I learned that when you communicate to people what is going on, they will pay attention. They didn’t care that I was only black person in school. I was Richard the tuba player, which is ultimately crazy, because that’s what you want. I’m not sure I want to be Richard the black tuba player. I wanted to be Richard the tuba player.”

White doesn’t feel he has been discriminated against or racially profiled in any way. He said that he appreciated that the Metropolitan Opera was the only organization in the field that kept an obscuring screen up during the entirety of the musician audition process in order to ensure player selection was based purely on skill, “and the Met has more Latin and African-American members than any other orchestra,” he said.

It was easier, White said, “to get into the NBA than win a professional symphony job as a tuba player.”

For White, the key to ensuring that orchestras became more diverse was to make instruments and teaching available to all children when they are younger, or a passion for music will remain the province of the wealthy who can afford private music lessons and instruments.

“I don’t believe in affirmative action,” White said. “I don’t want to go to an orchestra and think they’ve gone, ‘Hey, you’re African-American, we should put you in there.’ I don’t think the idea should be to give handouts, but rather hand out opportunity.”

William, Richard’s brother, told The Daily Beast of his sibling’s drive, “Coming from where he’s come from, all that struggle, he has never given in. He has excelled and made his way. He came from a difficult part of the community: You had to be sharp or get lost. He could have gone the street route and dealt drugs but he chose the school route, tuba. He has achieved so much. I’m so proud of him.”

William, who works at Walmart as a supervisor while also taking care of his father who is dying of cancer, is also happy to have a relationship with Richard now.

In times past, Richard, William said, didn’t know what he wanted from him. “He may have thought I wanted something from him. I tried to reach out all the time for a brotherly bond. I didn’t want money. I just wanted to build the relationship our momma wanted us to have. I did have a resentment towards him. I didn’t do anything wrong, but we were not doing what normal brothers do. But then Richard told me, it wasn’t that he didn’t want anything to do with me. He just didn’t know how to approach me.”

The brothers have now built a relationship, and speak by phone regularly and see each other when they can. In the film they make music together, using William’s fantastic freestyle rapping set over Richard’s tuba playing. “The fact he is acknowledging me is such an honor,” said Richard. “We may be biological half-brothers, but to me we are brothers-brothers. He is an example to me, to all of us, that you can achieve anything if you really believe in it.”

Music brought William and Richard together, William said. “He was the first person that got me into classical music, with a selection of classical music he made for me. I loved it. Listening to it made me feel closer to him. I love opera and classical. I’m a black dude in the hood listening to Beethoven, Bach, Tchaikovsky, and Pavarotti, and I understand and enjoy it.”

White’s favorite music to play is Bach and Bruckner. He laughed that he thought he should be living in the Baroque Era.

“There’s something very beautiful and unexplainable when I listen to those types of music and those composers. I hear Bach and Mahler in rap. Music allows me to go to a third dimension, it allows me to leave any issues with the world behind. I have a really good life because I’m a tuba player. My ultimate goal is to be a monumental figure in the world of classical music. I really just want to be the best me. I believe we are all just scratching the surface of all our potential.”

White has been with his partner, Yvonne, her three kids and puppy, for four years now. He loves her and is very happy, he said. He doesn’t have children of his own and doesn’t want them.

“It takes courage to admit that you don’t want to have kids,” said White. “I think more people should take care of what already exists. There are tons of kids in this world who can’t go to college without a scholarship. I would rather help other people before I help myself.”

His students have issues, and come to him for advice. “It really does feel like they are my kids.” Yvonne’s kids feel, to him, to have a life of privilege, “but that’s not their fault, it’s just my perspective. Watching the film really opened their eyes. It made them realize, they said, how privileged they were.”

With Lawrence Brownlee and Quincy Roberts, fellow alumni and dear longtime friends from the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, White is helping fund the Brownlee, Roberts and White Brothers in Achievement Scholarship, to be awarded to one student every year and worth $65,000, aimed at “underrepresented populations, including but not limited to financially challenged students and/or students with diverse cultural experiences.”

Alongside enjoying the prospect of having grandchildren, White said he wanted “to buy a tuba ranch and retire in New Mexico with Yvonne.” White said he was inspired by Harvey Phillips’ ranch. Phillips’ ranch was “a feel-good life embracing goodness, with a table in the kitchen that you didn’t have to reach for. It just rotated in a circle, and the food came around to you. That’s my dream now.”

“A tuba ranch,” he said, “is somewhere where people can come and eat chili or ramen noodles, and have beer 24/7 and play music. It will say ‘RAW Tuba’ as you enter. You can sing, play the tuba, play the tambourine, whistle.”

As White works on a memoir, he is alarmed by the financial crises, and bad financial treatment of members, afflicting American orchestras, leading to strikes at such institutions as Chicago Lyric Opera. The Baltimore Symphony does not have a single contractual player, he said. White had sued the New Mexico Symphony when it owed him $42,000.

“The music industry is a business, and we have to understand that,” White said. “It’s insane if you’re trying to operate off donations and tickets. It won’t cover 5 percent of your costs. I think we need to look at successful business models selling their products and emulate them. Orchestras have become so segregated, catering to an elite group of people. We’re ignoring 90 percent of the population. Justin Timberlake and Queen Latifah should be at these concerts, or whoever this generation wants to see.”

When he sees homeless people now, White said that “sometimes I feel like a hypocrite. I see them. They’re very clear to me. I see how I was homeless. Just as we are immune to gun shootings, I see how people get to be immune to homelessness. It’s gotten so out of hand we don’t recognize it as a problem right there in front of us. I don’t understand why I see a church on every corner and so many homeless people. It doesn’t add up. We are in a society where it’s every person for themselves, rather than one in which every person is taken care of. I think because of social media we all think we know more than we do. I don’t think a lot of things are real to us.”

White has made a list of things he still wants to do. “I want to make my first solo tuba CD. I want to be the first person to say I’ve given a recital on all seven continents, including Antarctica. I want to write a book, which I’m doing. I want to become a full professor, not just an associate. I want to be in an administrative position in a university in the next five years. I want to open the tuba ranch in the next year, year and a half.”

For White, from age 1 through 30, “you’re in school trying to figure it all out. 30 to 60 is adult responsibility, mortgage and all that, make sure the family is OK. 60 to 90 is you’re not going to be here forever. I want to stop working by 60, and enjoy the last 30 years.”

From 60 onwards, White hopes for a life of public speaking and service, but not running for office, which he would love to do but worries that his heart is “too pure” for it.

If White had “a story line” for the end of his life, he said laughing, “I would like to die fighting, swinging, not with a terminal illness. I’d like to die fighting a good cause, something worthy. When it comes it comes, but I ain’t going to lay down easy,” he said laughing. “If it comes in my sleep or something like that my reaction will be, ‘Oh damn.’ If comes any other way—hardship, illness—I’ll give it a battle royale. I’m not so Hollywood that I want to die on stage.

“At some point I won’t play the tuba. Do I want to die at 65 playing the tuba? Absolutely not. It has opened doors for me, but there are other things in life I want to do. The tuba has blessed me. I believe I am supposed to be a motivational speaker now. That’s what I believe my calling is.

“If I had one wish to give to the world, it would be to believe in the power of the imagination and be kind. That’s really my message to the world. I say in the movie, going to the moon is not about billions of dollars, it’s believing the impossible is possible.”

For all his success and warm eloquence, White said he always believes he is not good enough, and on he works to the detriment of his health; in October he gets pneumonia (this year is the first year he hasn’t).

He has never suffered from depression, but does have “anxiety about letting people down. I’m not sure how to process people telling me they love me via social media, or tell me they remember me from when I was young. I can tell they’re sincere. I’ll have to talk to someone about that eventually. My life is so controlled as an orchestral musician, I don’t know where to put things like this which don’t have an obvious compartment.”

White said he has “overwhelming moments of sorrow and joy at the same time when I think about where I’ve come from and been. I’m laying on that cardboard. I’m cold, I’m freezing. I don’t know where my mom is but at least I have a piece of cardboard. Then I’m in Rochester about to play in a quintet. I think, ‘Wow, my mom gave me up, but boy was that a heroic thing for her to do.’

White has moments of “complex duality,” he said. “People talk about good and bad, high and low, and sometimes I experience those all at the same time. From time to time, just like when I was on the streets, there are moments of silence where I just think. I don’t necessarily come away with answers, but the one thing I did when I was younger on the streets and still do now is give myself a big mental hug.”

R.A.W. Tuba will be screened at the Baltimore School of The Arts on February 8 at 7 pm, with more screenings around the country to follow over the course of the next year.