After the 2014 police killing of Laquan McDonald, Chicago officials appointed a commission to study policing in the city. When the commission issued its report two years later, Steve Bogira of the Chicago Reader noticed that the report bore striking similarities to a report issued after the death of Daniel Claiborne, a 70-year-old Black man, also at the hands of police.

Both reports, Bogira noted, found that residents in the city’s minority neighborhoods were frequently subjected to illegal stop and frisks. Both found that Black and Latino residents reported frequent verbal harassment and humiliation from police. Both reports found that police misconduct complaints were almost never sustained, and often weren’t thoroughly investigated. The Claiborne report found a 43-point disparity between the percentage of the city’s population that was Black and the percentage of Black people shot by police. The McDonald report found a 42-point disparity.

Here’s the punchline: the Claiborne report was issued in 1972—43 years before the McDonald report. Over nearly a half century, very little had changed.

But it isn’t just Chicago. After the Watts riots in 1965, Los Angeles convened the McCone Commission, which found similar problems with policing in that city. After the beating of Rodney King 25 years later, the Christopher Commission would come to the same conclusions.

In her polemical new documentary Riotsville, U.S.A., director Sierra Pettengill introduces fascinating new archival material about policing, dissent, and how the government views protest, but the bleakest takeaway is a familiar one—this country has a stubborn refusal to learn from its past. After a half-century of scandals, reports, studies, and commissions exploring race, policing, excessive force, and protest, we’re still having the same arguments. We’re still making the same mistakes. We’re still ignoring the same evidence.

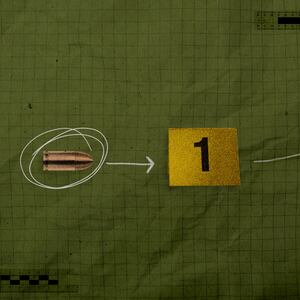

A scene from Riotsville, U.S.A.

Courtesy of Magnolia PicturesThe film’s title is a reference to the fake city fronts the U.S. military used in the 1960s to drill soldiers on riot suppression and crowd control. In the archive footage uncovered by Pettengill, U.S. troops practice anti-riot maneuvers in front of colorful storefronts—a drug store, a watch repair shop, a bank—that look as if they were pulled from the stage of a high-school theater production. As other soldiers (badly) play the roles of protesters and rioters, the drills grow increasingly tense. Helicopters swoop in. Tear gas canisters bloom noxious fumes. Tanks roll past.

Meanwhile, as the simulated protest escalates to simulated violence, a few hundred military brass and VIPs watch from a set of bleachers as if it were all a sporting event. The visuals are stunning, apocalyptic, and at times almost comical, like scenes from a dystopian B-movie.

The first unsettling thing to hit about the Riotsville drills is that it’s all being done by the military. Free societies tend to keep the military out of domestic policing, and those that don’t tend not to remain free for long. As you watch Jeeps, helicopters, and tanks patrol a facsimile of a U.S. city, it’s hard not to think you’re watching the blueprint for a military-police state.

Masked National Guardsmen fired a barrage of tear gas into a crowd of demonstrators on the campus of Kent State University May 4, 1970. When the gas dissipated, four students lay dead and several others injured.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesBut we’re also watching the film with the knowledge of what happens next, and that particular concern wouldn’t come to pass. While it’s true that over the ensuing decade, there would be several occasions in which National Guard troops would be called in response to civil unrest, sometimes with horrific consequences, we never reached the point where, as one Black activist predicts on a talk show in Riotsville, the military would become an ever-present force in U.S. urban areas.

But what did happen isn’t much better. The Watts riots gave birth to the concept of the SWAT team, an elite police squad modeled after military units like the Navy Seals or Army Rangers. The idea made some sense at the time. It seemed prudent for cities to have the specialization and firepower to respond to the rare emergency in which lives were at immediate risk—riots, active shooters, hostage takings.

But by the mid-1990s there would be a SWAT team in every moderately sized police department in the country. Militarized police forces would become the de facto method for serving search warrants, the default response to protest, and in some places were used even for routine patrol. Militarization became the norm.

The reason to be wary of using soldiers for domestic policing is that soldiering and policing are two very different jobs, with two very different aims. One is about protecting; the other about destroying. If, instead of using soldiers to police, we’ve armed, dressed, and trained our police as soldiers, we’ve only created a different version of the same problem.

Which is why, despite their absurdity, some of the scenes in the Riotsville archive footage—heavily armed soldiers kicking down doors, men in riot gear lining up against peaceful protesters—don’t look so foreign at all.

A scene from Riotsville, U.S.A.

Courtesy of Magnolia PicturesPettengill supplements the faux city scenes with scenes from actual protests of that era, interviews with 1960s focus groups and, most interestingly, clips from old talk shows in which panelists discussed race and policing in America.

The talking head clips are wonderfully of their time and place—flat tops, grainy video, spiraling wafts of cigarette smoke. But here too, take out the fat ties and Brylcreem, and the debate itself hasn’t changed much at all. In an extended clip from a Public Broadcast Laboratory special, an anchor moderates live feeds from civil rights gatherings in Newark and Detroit while, in another feed, the fuming head of the Fraternal Order of Police brushes off activists’ anger, insisting that police abuse is rare, and that cops defend the thin line between society and anarchy. The discussion itself sounds very much like the various cable news “town halls” after the George Floyd protests.

The documentary also spends a lot of time on the first of the many commissions to come—the Kerner Commission, a blue ribbon panel set up by Lyndon Johnson to study the cause and response to the riots of 1967. The commission was mostly made up of white, establishment politicians—mayors, governors, and congressmen—along with the Atlanta police chief and the head of the AFL-CIO. The only non-white member was the head of the NAACP at the time, which is why the panel was criticized by activist groups for its lack of representation.

Yet the commission’s report still found rampant and persistent police brutality in the cities that had seen rioting. It found that the police response to protests was typically heavy-handed and overly aggressive, and more likely to provoke violence than to prevent it. And while it found ample documentation to support the grievances of protesters, it found that those grievances were often ignored. The activist H. Rap Brown, who was behind bars for “inciting a riot” at the time, later remarked that he was incarcerated for saying the same things the Kerner Commission had put in its report.

Since the Kerner Commission, there have been too many other commissions, studies, and reports to count. The U.S. Department of Justice has produced volumes of jaw-dropping reports about police abuse and misconduct across the country—including, just in the last decade or so, in Ferguson and St. Louis County, Missouri; Cleveland; Baltimore; Chicago; New Orleans; Minneapolis; San Francisco; and Milwaukee, among others.

A few important lessons echo throughout the five decades of reports and studies since the Kerner Commission. The first is that riots tend to happen in cities with long histories of police abuse, racism, and corruption. They’re rarely about a single incident. Second, they tend to happen after people in those cities complained about such abuses for years, but felt they’d been ignored.

Finally, they also tell us something important about how police respond to protest and civil unrest: When law enforcement officers treat protests as an exercise of the First Amendment—as a right the police are obligated to protect—there’s less likely to be violence. When they treat protesters as a threat and show up expecting violence, they can end up provoking it.

Protesters sitting on the ground are confronted by riot police during the World Trade Organization’s 1999 conference in Seattle.

Christopher J. Morris/Corbis via Getty ImagesThis has happened over and over again. Norm Stamper, the former police chief in Seattle, has said the greatest mistake of his career was the militaristic, heavy-handed way he and his department responded to the 1999 WTO protests in that city. Subsequent analysis of the violence during the protests show it was provoked by the officers’ too-quick, inept deployment of tear gas. Stamper has said he regrets that the way he responded to those protests has since become the norm.

The 2015 DOJ report on the police reaction to protests in Ferguson, Missouri after the shooting of Michael Brown concluded that the violence in St. Louis County erupted only after police showed up at a peaceful protest with snipers, dogs, riot gear, and armored vehicles. The police presence “served only to exacerbate tensions between the protesters and the police,” the report concluded, and “defeated… the perception of procedural justice and legitimacy.”

There’s plenty of academic research on this as well. The psychologists Clifford Scott and Steven Reicher have studied a generation of unruly crowds—from the 2011 London riots in response to a police shooting, to the 2019 protests and riots in Hong Kong, to soccer hooligans in the 1990s.

They’ve found that crowds, especially protest crowds, generally tend to self-police when it comes to rioting and violence. Crowds with a shared interest, especially protesters, want to be heard and seen as legitimate. But once police begin to use force—particularly if it’s seen as excessive or arbitrary—the crowd begins to see police officers as a common enemy. The self-policing stops, and the violence spreads.

By the time of the George Floyd protests in the summer of 2020, there was a palpable difference between the police agencies that had heeded these lessons, and those that hadn’t. In cities like Newark, Flint, and Camden, police officials attempted to identify with protesters, even marched with them. Those cities saw comparatively little rioting and property damage. Kansas City provides a particularly good example. After an outbreak of violence during the first week of protests, police officials met with protesters, listened to them, and then pulled back their presence. The violence abated.

Policemen walk with protesters during the City Collective Prayer March on June 7, 2020, in Norfolk, VA. The event was organized to honor George Floyd, an African-American man from Minnesota who died in police custody on May 25, 2020.

Annette Holloway/Icon SportswireIn Norfolk, Virginia, the police chief reached out to protesters early on, and marched with them. The city saw little violence. But in nearby Virginia Beach, police responded quickly in full riot gear. Violence followed. One man who attended both told a local paper that police in Norfolk “were in light gear or T-shirts,” while police in Virginia Beach “had come expecting a fight.” So they got one.

A ProPublica review of 400 protests that saw some kind of violence found that in nearly half, the violence was either caused or escalated by inappropriately aggressive police tactics.

Of course, some cities saw violence that had nothing to do with the presence of or reaction from police. The lesson here isn’t that an appropriate police response will always prevent violence. It’s that the wrong police response is more likely to provoke it.

In the Riotsville footage of soldiers marching through hastily constructed cities, we see the seeds of the precisely wrong attitude toward protest take form. It’s an approach to public safety that sees protest not as a constitutional right worthy of protection, but a threat to order and stability; that sees protesters not as citizens with legitimate grievances but as subversive elements to be suppressed.

At one point in the documentary, an unidentified Black panelist on a 1967 talk show laments the formation of the Kerner Commission. “That’s what we do in this society,” he says. “We appoint a committee, and we investigate. Ergo, ‘something’s being done.’ And that’s just simply not true.”

But though the commission didn’t get everything right, it did identify a lot of what went wrong in 1967. The problem wasn’t the report itself. It’s that once it was published, nothing happened. Now, countless commissions, blue-ribbon panels, and official studies later, we still know what works. We still know what doesn’t. Yet little has changed.

This is the most chilling thing about Pettengill’s documentary—for all the weird, other-worldly imagery of the Riotsville drills, the film feels way too familiar.