When the history-making politician Ritchie Torres won his House seat in November, he told his mom, Debra Bosolet, “This moment belongs to you as much as it belongs to me, because I would not be here without your unconditional love.”

On Sunday, when the 117th United States Congress convenes, Torres will start his new job representing New York City’s 15th District—which includes the South Bronx, where he grew up. When he returned from his freshman orientation at the House of Representatives, he had dinner with his mom, his “hero.” She told him, “This is the first time I’ve had dinner with a congressman.”

Torres said he was smiling as he recalled the moment to The Daily Beast in the mellifluous, even-toned way he speaks. It is the same tone he employed throughout our conversation, whether discussing politics or the extremely personal—the bullying he endured as a kid, growing up in poverty, contemplating suicide, the mental illness he has confronted, contracting the coronavirus, his disdain for “incompetent” New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, his pride in being the first Afro-Latino, out-LGBTQ member of Congress, and his determination to be a politician representing the Bronx on his own terms.

Torres’ calm, precise speech doesn’t sound like a politician’s usual audio mask or the result of polished media training. Instead, it seems to be the voice of someone who by nature values reflection over bombast but who is still emphatic on what he does and does not believe. His proudly held independence includes, for now at least, respectfully separating himself from the “Squad,” and its figurehead Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who represents the neighboring congressional district to his. Politicians endlessly bang on about being their own people; Torres really means to embody that ambition, and in D.C.—land of greased wheels and questionable compromises and deal-making—he intends to hold true to it.

“I am the most grateful and gratified man in America,” Torres said. “I never thought in my wildest dreams that I would embark on a journey from public housing in the Bronx to the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C.”

Torres, 32, originally made history as the first out-LGBTQ elected official from the Bronx, the first out-LGBTQ member of New York City’s congressional delegation, and youngest member of New York City Council for the 15th District, when he was elected in 2013, aged 25.

Making history was “deeply gratifying,” Torres said. “Representation is not only a burden, it’s a blessing. I can serve as a role model and inspiration to people who see their lives and experiences in mine. I hope it inspires them to see themselves in government and public office. New York City is the birthplace of Stonewall and the LGBTQ civil rights movement, and who would have thought the first openly LGBTQ member of the New York City congressional delegation would come not from Chelsea or Hell’s Kitchen, but from the South Bronx? That represents a distinctive kind of breakthrough in LGBTQ representation in politics.”

“I am more hopeful I will have a greater ability to effect change as a congressman than as a city councilman,” Torres said. “At the local or state level, you’re largely planning in the garden of the federal government. What you do locally is the administration of federal programs, and so you realize to have a systemic impact you have to be a policymaker in Washington, D.C., because that is where rules are set, purse strings are held, and that’s where the future of the country is largely determined.”

For Torres, Congress is a “natural progression” from serving on the New York City Council. He has an “on-the-ground knowledge” of how federal policies operate at a local level and so is “cautiously optimistic” he will be able to make an impact as a congressman. “I also have no illusions about the inertia in Washington, D.C. I recognize it is a long game. It’s a hierarchical institution that recognizes seniority. I’m going to work my heart out to move the ball as much as I can, as far as I can.”

Torres said he became a politician and elected official “by accident.” He had dreamed of becoming a teacher or a lawyer. But 15 years ago he was introduced to his political mentor, former New York City Council member James (known to all as Jimmy) Vacca, which set Torres on his history-making path that has led him to Congress.

Vacca, now a distinguished lecturer of Urban Studies at Queens College at the City University of New York, told The Daily Beast: “I knew from the beginning that Ritchie was destined for great things, but you never know, especially in politics, what opportunities will arise. You never know when or if those opportunities will arise. He’s perfect for Congress and will become a valued member of the House. His grasp of policy is phenomenal.”

“I never thought I would be elected to office because in truth I am an introvert in a business mostly designed for extroverts,” Torres said. “Extroverts are energized by social interaction. I’m often exhausted by it. I am someone who needs personal time for deep thought and reflection. Life as an introverted politician has been a challenge, but I have mastered it.”

As a public speaker, and during this interview, Torres does not seem shy. But this outwardly confident, charismatic public personality, said Torres, is “an acquired skill. The more you practice public speaking, the better you become, the better you project it. I remember that when I first ran for City Council I was so anxious about public speaking I’d have to drink a glass of wine before any speaking engagement.”

Red or white? “Red wine, a Merlot or Cabernet. Eventually I became at ease with public speaking. I am a contemplative person. I love to take time to read, think, and speak to myself. I love to think about the larger questions affecting our politics. Even though, ironically, I have no college degree, I am deeply philosophical about how I approach politics.”

Can philosophy be practically applied to policymaking? “I feel like philosophy is universally applicable because it teaches you how to think critically. That’s not just useful in politics but in every human endeavor.”

“I have been blessed to have the friendship, love, and support of people who believed in me, more than I believed in myself.”

When he was a child, Torres’ maternal grandfather said to him, “You’re going to be somebody one day.” He did not live to see his grandson become a New York City Council member and now member of Congress, but when Torres won his council seat, Torres said to himself, “Grandpa, I am somebody.”

“He saw something that I did not see,” Torres said. “And I have been blessed to have the friendship, love, and support of people who believed in me, more than I believed in myself.”

Torres was 17 when Vacca—then district manager for Community Board 10—approached Robert Leder, Torres’ then headteacher at Herbert H. Lehman High School, asking if Leder could recommend a young, talented, civically minded student who would serve as district manager for the day. Leder, who died in 2018, immediately recommended Torres, who was captain of the school’s law team and had served in the Coro New York Exploring Leadership Program.

Vacca recalled being dazzled by Torres’ skills and confidence. “There are 110,00 people in the district. A district manager has to make sure people get services delivered to the community. I called Robert Leder, who immediately recommended Ritchie. He said he was extremely bright and would benefit from the experience. When I met Ritchie, it was like ‘Wow.’ I knew he was one bright youngster.”

He recalled that Torres, in his day on the job, participated in meetings with the neighborhood’s senior citizens “as an equal, as if he were a long-serving member of the community. He understood the problems.”

Vacca said he didn’t want “someone that young with such leadership qualities to slip through my fingers.” In 2005, when Vacca ran for City Council, Torres offered to help in his campaign. Vacca recalled, laughing, that when Torres went door-to-door canvassing for him, he had described Vacca as “loquacious” to one couple, who then phoned Vacca to query why one of his canvassers was using such language. “Are you sure he’s advocating for you?” they asked Vacca, asking what the word meant.

When Torres checked in with him a few days later, Vacca said to him, “Ritchie, you’re doing great, but you have to speak the language of the voter.” (Or, possibly, we might all benefit from expanding our vocabularies.)

When Vacca won his City Council seat, Torres became his intern, rising to becoming his housing director, organizing tenants’ associations and overseeing landlord/tenant mediation. Then Torres won his own seat, and mentor and protégé served alongside each other for four years.

Ritchie Torres is arrested with other activists at a rally demanding that the Trump administration abandon proposals to cut the Housing and Urban Development's (HUD) budget on April 20, 2017, in New York City.

Spencer Platt/GettyFrom 2006 to the present day, Torres has worked in one capacity or another on the New York City Council. “I’m about to resign my council seat and leave behind the institution I’ve spent half my whole life and all my professional life in. It’s a very bittersweet moment for me,” he said.

Torres’ even-toned voice is in one way deceptive; he is passionately devoted to fighting for his constituents. The New Yorker noted last year that as a council member Torres had became “known for his aggressive interrogations of city officials.” Had he achieved all he wanted to on the City Council? this reporter asked. “You never achieve everything, but I have established myself as a leading advocate for affordable housing and poor people of color in public housing.”

As chair of the council's Committee on Public Housing, Torres oversaw the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), which manages public housing for about half a million New Yorkers—and he invited its residents to voice what their demands for change, and held public hearings over the same. “I think of NYCHA as a city unto itself, the largest city of low-income Black and brown Americans in the country. I feel like I have been the leading advocate, the leading voice, for America’s largest city of low-income Black and brown Americans.”

Vacca said Torres was a “very independent, strategic politician. Ritchie has his eye on the ball and the end result. And he’s analytical. He very much enjoys conversation. He enjoys reviewing options. He can be opinionated but also a good listener. He’s very methodical. He would think, ‘If I tell the housing authority there’s lead in the apartments, I’ve got to have documentation and make sure they do what they have to do.’ When he questioned agencies at the council, they had better come prepared. He’s done his homework.”

Torres concedes that NYCHA faces “management challenges” but insists it has been “plagued by years of federal disinvestment. If you starve an institution of funding, as the federal government has done to NYCHA, then you’re setting it up for failure. Children are being poisoned by lead, senior citizens are freezing in their homes during the cold of winter, disabled residents are stranded in top floor apartments because elevators break down, and asthmatics are struggling to breathe because of mold in their apartments. We need more funding in public housing and fundamental reinvestment in public housing.”

For Torres, NYCHA has the potential to be “a laboratory for a green revolution,” imagining its apartment blocks featuring rooftop gardens and energy retrofits. Torres believes public housing can become “the gold standard” for affordable housing in America. He hopes to effect real change with a seat on the House Financial Services Committee, which has jurisdiction over not just finance but also housing.

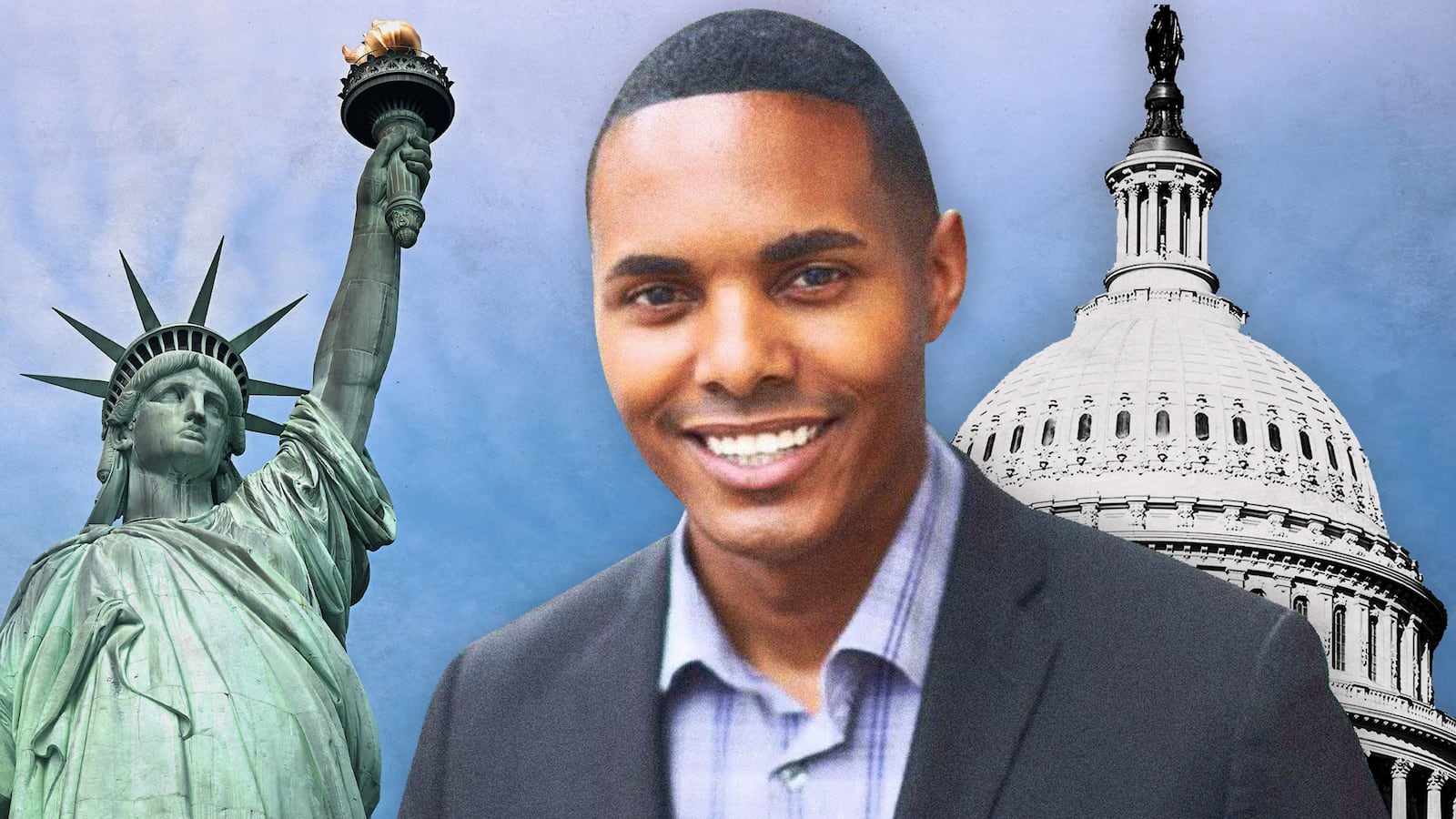

Ritchie Torres.

Courtesy Torres for CongressTorres is proud to have triumphed in a crowded and competitive primary over presumed frontrunner Rubén Díaz Sr., “the worst homophobe in New York State politics,” as Torres calls him. Díaz Sr.’s history of voluble bigotry includes opposition to marriage equality and his claim that the “homosexual community” controlled the New York City Council on which Díaz Sr. and Torres served together. “It’s a powerful testament of how far we have come as a society,” Torres said of his victory. “I’m part of a new generation of leaders who are more progressive, more disruptive, and every bit as diverse as America’ itself.”

“I think Ritchie is ambitious,” said Vacca. “He ran for Congress against a frontrunner who no one thought could be beaten. All of us in politics have to have ambition. I think Ritchie took on a giant in the borough and had to have ambition to do it. If he learned anything from me, it was to be very locally focused and in tune with the community.”

But do not expect Torres to be easily aligned with D.C.’s most famous progressives. Most recently, Torres told the New York Post: “I came to observe that there are activists who have a visceral hatred for Israel as though it were the root of all evil. The act of singling out Israel as BDS [the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement] has done is the definition of discrimination.”

Torres, who has maintained his distance from the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) as they emerged as a power in local politics with Ocasio-Cortez’s election to Congress in 2018, denounced the group after its New York City co-chair Sumathy Kumar declined to answer whether the DSA supported the existence of Israel as a state. Afterward, Torres tweeted, “The leadership of the DSA declines to affirm that the state of Israel should exist. ‘Insane’ is the word that comes to mind.”

The Post said Torres said he would not join the Squad. “I would never make an announcement that I would not join something. That’s silly,” Torres told The Daily Beast. “What I have said is that I intend to join the congressional Hispanic caucus, the congressional Black caucus, the LGBTQ caucus, and the progressive caucus. Those are the caucuses I am joining. I am often asked if I am going to join the Squad. My answer is simple. I refuse to define myself in relation to someone else. I prefer to be my own person, and I prefer to be judged based on my own story and my own record, on my own terms.”

That sounds like a no. Is it fair to assume Torres is not as far left or radically progressive as members of the Squad are?

“It might depend on the issue, but that strikes me as a fair characterization,” Torres replied.

His congressional victory, then, may in time show the plurality of what “progressive” can encompass, beyond both self-definition and it being a favored blanket insult of the right. Torres also made clear to the Post he would not be drawn into a public slanging match with Ocasio-Cortez, saying she had been “unfailingly gracious.” Some have called Torres a centrist; his tone is certainly one of a pragmatist. It will be fascinating to watch how he orbits D.C. and how D.C orbits him.

“Ritchie is very independent,” said Vacca. “Some of his views do not coincide with the Squad’s. Although Ritchie is very progressive, he is an independent thinker. He will go his way. I think Ritchie is going to be an asset in the House, but I don’t think that is contingent on him joining the Squad. He’s an analytical thinker and knowledgeable. He reads, reads, and reads. He makes his decisions based on the merits of an issue.”

A candidate’s sexuality and race can still be weaponized against them, Torres said. “We saw it in the 2020 election against candidates like Gina Ortiz Jones and Jon Hoadley, and several others, so it would be premature to declare ‘Mission accomplished.’ We have to be as vigilant as we’ve ever been in fighting racism, homophobia, hate, and fear in every form. Keep in mind that Donald Trump won 74 million votes. Trumpism might outlive the Trump presidency, so it is premature to declare the politics of fear and hate have been defeated.”

The passage of the Equality Act, which would enshrine anti-LGBTQ discrimination in law, is dependent on Democrats winning control of the Senate, Torres said. “As long as Mitch McConnell sets the agenda of the Senate, there is going to be a real ceiling for how far the country can move forward. Senate control is essential, a non-negotiable. The single greatest obstruction on the path to progress is Mitch McConnell.”

“Religious freedom” and “religious liberty,” the battle cries against LGBTQ equality being employed by the Trump administration in the courts and local legislatures, “keeps me up at night,” said Torres. “The single most insidious threat to LGBTQ equality in every form is the weaponization of ‘religious liberty.’ For me, ‘religious liberty’ was originally intended to be a shield that protects from discrimination. It was never intended as a sword that enables you to discriminate.”

The issue is at the heart of a foster care case currently before the Supreme Court, now with a 6-3 conservative majority, which The Daily Beast has reported on.

“If the Supreme Court radically reinterprets religious liberty as a license to discriminate, that will have the effect of eviscerating the civil rights of the LGBTQ community at every level of government,” said Torres, meaning any person or organization in America “can discriminate against the LGBTQ community under the guise of ‘religious conscience’ and ‘religious liberty.’ It’s an open-ended assault on the equality and humanity of my community.”

There is only one antidote, said Torres. “Expand the Supreme Court. Because the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Constitution trumps the Equality Act. The only solution lies in expanding the court and creating a progressive majority, and taking back the Supreme Court stolen from us at the hands of Mitch McConnell.”

Torres means Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s seat, now occupied by Amy Coney Barrett, but he is also referring to Merrick Garland’s ruthlessly undermined nomination.

“For me, Democrats should have no illusions about the Machiavellianism and malevolence of Mitch McConnell,” Torres said. “The Democratic Party has to be every bit as relentless and ruthless in building power as the Republican Party under Mitch McConnell has been in building Republican power.”

Torres says the court should expand by “at a minimum” one seat. “I am not advocating for endless tit-for-tat, just for the one seat that was stolen from the Democratic Party at the hands of Mitch McConnell. Are the votes there for court expansion? No. I’m acutely aware of that. But if the question is how to prevent the weaponization of ‘religious liberty’ against the LGBTQ community, the only solution is court expansion and court rebalancing, or else we might be doomed.”

Many feel the Democrats simply aren’t as ruthless as the Republicans.

“If we continue to play softball, we’re going to be outmaneuvered by the Republican Party,” Torres said bluntly. “We might win the two Senate seats in Georgia. The Democratic Party might control all the political branches of government—the presidency, the House of Representatives, and Senate—but what good is Democrat control if it is struck down by the right-wing judicial activism of the Supreme Court? That activism has the potential to negate the value of Democrat majorities in the House and Senate and a Democratic president.”

That the Supreme Court came so close to destroying Obamacare “sends the message there are no limits to the damage that a right-wing Supreme Court can do to a progressive agenda.

“It’s why Republicans have been organizing relentlessly at the courts. If you can’t win at the ballot box, you’re going to try and win in the courtroom.” The recent pro-conversion therapy ruling in the 11th Circuit, by two Trump-appointed judges, “could be an omen of things to come,” said Torres, presaging “a broader weaponization of religious liberty and the resurgency of a Lochner-era Supreme Court.”

“My politics were formed in the crucible of lived experience in the Bronx, in public housing, and in poverty.”

Torres grew up with his mother, twin brother, and sister. Debra told The New Yorker in 2016 that she named him after Ritchie Valens, having seen the film La Bamba when she was pregnant with him. Torres’ father never lived with the family. (Debra did not respond to a request for an interview, or a set of questions sent by The Daily Beast via Torres’ spokesperson.)

The young Torres was extremely studious, “but mostly mischievous. I had more than my fair share of fights as a kid. I was assaulted by gangs in third grade and in high school. But over time, I came to realize there was more power in the mind than in the fist.”

“Debra is one of the nicest people you could ever meet,” Vacca said of Torres’ mom. “I think very highly of her. They are very close, and she is very supportive of him. She’s a follower of news and policy. I think Ritchie has a sensitivity to the struggles people go through because his mom went through those struggles. He saw what his mom went through in public housing. Her perseverance is very impactful on Ritchie.”

His mother went from one low-wage job to another, said Torres. “There were moments when she was an assistant car mechanic, a school server, and moments when she was unemployed. At its worst moments, she was raising three of us on the minimum wage of the 1990s, which was $4.25 an hour. Frankly, I don’t know how she pulled it off, but she did.

“How do you raise three children in the most expensive city in America on 4 dollars, 25 cents for an hour? For me, my mother is my hero. The essential workers and essential mothers of the South Bronx are heroes. They do the impossible every day, and these are mostly women of color who have raised our families and risked their lives through the peak of this pandemic.”

Torres emphasizes how his politics are intensely personal. “The central question I ask myself as a public official is, am I doing right by the essential mothers and essential workers of the South Bronx? Am I doing right by people like my mother, who have struggled and sacrificed and suffered so that I had a better life than she did? That is my guiding and animating principle in all that I do. My politics were formed in the crucible of lived experience in the Bronx, in public housing, and in poverty.”

Growing up, Torres said he knew the family was struggling. “I knew my mother was uncertain if we had enough money to put food on the table, to pay the rent, and hold on to our home. I was keenly aware of the poverty of our family, and struggling to get by.” His mother was loving but also a strict disciplinarian who would hold Torres “accountable.” If he ever hung out with the wrong crowd, “she would always steer me in the right direction.”

Torres recalled being beaten badly by a gang of students in the schoolyard of his elementary school, aged 7 or 8. The school did not call his mother; she only discovered he had been beaten when she saw the bruises all over his neck. “No one came to my rescue. You had this gang of students beating the hell out of me, and the school safety guards largely stood by.” One on one, he could have defended himself, but not against a gang.

The leader of the elementary school assault went to torment a classmate of Torres’ for the next 10 years, “and he wound up murdering him outside his own home. I was assaulted by the same person who murdered a friend of mine almost a decade later. There is a sense in which I consider myself lucky. When I heard what had happened, the first thought that came to my mind was ‘It could have been me.’”

His friend had done “everything right”: captain of the football team, excelled academically, on the path to college. “Then, on one day in broad daylight, he is murdered outside his own home, drenched in his own blood, and his mother comes out screaming. That could happen to anyone. The narrative of ‘pulling yourself up by your bootstraps’ ignores the role of chance in our lives.”

“The central mission of my life is to break the cycle of violence that cuts short the lives of many young people who are simply in the wrong places at the wrong times,” said Torres.

In high school, Torres discovered a talent he had no idea he had: public speaking. He became the captain of Lehman’s law team and twice led the school to winning the city’s moot-court championship. He delivered convincing arguments in the face of rigorous questioning from real judges, in re-enacted cases, such as Brown v. Board of Education, in which the Supreme Court ruled that the legally mandated racial segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. Torres read the whole case in high school “and found myself inspired by what the Supreme Court did.”

“It required you to think on your feet, to read, think, speak, and write,” Torres said of arguing the cases. “The skills I learned in moot court are skills I have brought to bear in politics. It was one experience in high school that had a formative impact in my life. It was rigorous preparation for the intellectual work of governing and policymaking.”

Torres kept his sexuality to himself for years, “for fear of not only rejection but also violence.” At 16/17, via MySpace, he found out a teacher of his was LGBTQ; Torres approached him and came out to him. “I had had no visible LGBTQ role models in my life, and this person inspired me to come to terms with who I was.” It was the first time he had acknowledged his sexuality to someone else, and he began the process of coming out, which culminated in his successful run for City Council.

“When I ran for City Council, I decided I was going to be out not only to the select few but to everyone. I was going to be fully out because I felt like it was important for me to be honest with my constituents,” Torres told The Daily Beast. “If you are dishonest about your personal life, you’re inclined to be dishonest about your political life. When it comes to integrity there’s no compartmentalization. You either have it or you don’t, and I said I would rather live a life of integrity and authenticity. So I ran as an openly LGBTQ candidate and became the first openly LGBTQ official from the Bronx.”

Vacca said that when Torres ran for council, they wondered if his sexuality would be an issue; it was not. Vacca himself came out in 2016, wanting—like Torres—to be “totally open and transparent” about who he was to his constituents.

When Torres came out to his mother, she “lamented the fact she might never have grandchildren, which is a misconception, but my mother loves me.”

Torres suffered badly from depression in his later teenage years and early 20s. It was so bad he dropped out of New York University as a sophomore. “You can never reduce depression to one variable. It tends to be a combination of factors. My sexuality might have been a factor; the death of my grandparents and the history of depression in my own family might have been factors. I dropped out of college because of depression, and it became so severe there were moments when I thought of suicide. I tell people I would not be alive today, much less a member of the United States Congress, were it not for the mental health care which saved my life.”

Torres was hospitalized for a few weeks, which were formative, “because I was able to find treatment that set me on the path to rehabilitation.” Vacca appointed him to serve as his housing director, “and gave me the chance to rebuild my life, recover from depression, and find my calling in public service. You’re only as strong as the support you have in your life, and I’ve had some of the greatest supporters who have believed in me more than I have believed in myself.”

James Vacca.

AlamyOf that time, Vacca told The Daily Beast, “I realized Ritchie was going through a bad period, and I guess my protective streak clicked in. I was always very supportive and protective of my staff. Ritchie often had no clothes on his back, often had no place to stay, and often had needs for mental health counseling and services. I wanted to be supportive. There were times when I told Ritchie that he could stay in my office overnight. There were times we had very serious conversations.

“Ritchie had many rough patches. He never told me he was thinking of suicide. I knew he was very depressed, and I suspected he may have thought of it. I tried to support him, and I hope more people come into public life, like Ritchie, able to talk about these experiences and help others by doing so.”

Today, Torres takes a daily anti-depressant. “It enables me to be a functioning, productive public servant,” he told The Daily Beast. “I took it for the seven years when I was on the City Council and I will take it as a member of Congress and feel no shame in admitting that I take an anti-depressant, and take no shame in admitting I have struggled with depression.

“As a public figure I feel a deep sense of obligation to break the silence and stigma that often surrounds mental health. If I was silent about my own struggles with depression, then I would be perpetuating the stigma. I would be part of the problem rather than part of the solution.” He still has “depressive moments, depressive episodes, but it’s much more manageable with an anti-depressant.”

Everyone should be mindful of their mental health, said Torres. He is not concerned about whether his depressive episodes could affect his ability to do his job. “I am confident, just as I survived the rigors of New York City politics, that I will excel in Congress,” he said.

“I contracted COVID-19 myself at the peak of the pandemic. Thankfully it was manageable.”

Torres is confident that the worst of the coronavirus is behind New York City and the Bronx. “What we need now is not only the vaccination for COVID-19 but also a structural vaccination for the deeper inequalities that have been laid bare by COVID-19: racial inequalities, health inequalities, and digital inequalities. That should be the work of the Biden administration over the next four years.”

Torres lost constituents and friends to the virus. “And it’s personal for me. I contracted COVID-19 myself at the peak of the pandemic. Thankfully it was manageable. I had to quarantine myself at home for two to three weeks. I had symptoms resembling those of the flu, but nothing that required hospitalization. It was a terrifying experience, first because I had to keep my distance from all friends and family, including the person I love the most, my mother, who at the age of 60 is in a high-risk category; and second because I had an infectious disease that brought our whole society to a standstill. It was an experience like no other, and COVID-19 has been a catastrophe like no other.”

Torres has very different views of how Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio have discharged their pandemic-related duties. Cuomo, he thinks, has been an “extraordinarily effective communicator.” Torres’ mother, like so many, found Cuomo’s daily press conferences to be reassuring and clarifying, for New Yorkers and Americans in general.

“Communication is an essential element of effective leadership,” Torres said. “To be an effective leader you have to be effective communicator. No one was more effective in communicating during COVID-19 than Governor Cuomo.”

However, de Blasio, said Torres, has been “a profound disappointment. Bill de Blasio is a unifying figure who manages to be despised by left, right, and center. The one thing everyone agrees on is the incompetence of Bill de Blasio. His management of the pandemic was the most egregious example of his fecklessness.”

Torres skewers de Blasio for the “mismanagement” of remote learning, his “erratic” opening and closing of schools, his refusal to shut down the city in early March, and his decision to go to the gym the night before New York’s shelter-in-place began. “His decision making was erratic in the moment of greatest crisis.” For Torres, “the greatest challenge confronting both the city and country was not COVID-19 per se, but COVID-19 compounded by a crisis of leadership—and in New York City we have a crisis of leadership.”

Do any of de Blasio’s vying mayoral successors hold the solution? “Potentially,” Torres said crisply.

Does he have a favored candidate? “Stay tuned.”

Ritchie Torres.

Courtesy Torres for CongressTurning 30 was not a big deal because Torres did not feel he had a conventional 20s. He ran for public office at 24 and became a City Council member at 25. “I felt like I became an adult much earlier than most people do. I had a heavy responsibility at a young age. I had to govern a council district larger than most cities in America. I felt like I skipped my 20s and went directly to my 30s.”

This reporter asked if love was important to Torres. “Love in the form of family and friendship is immensely important to me. It’s indispensable, but as far as romance…” Torres’ voice tailed off, then that resonant, even tone reasserted itself. “My focus is on Congress. I am intent on excelling as a member of Congress. Everything else is secondary.”

Is he in a relationship? “I am single. I am married to the district, if that counts. I am married to the South Bronx.”

Does he want to be in a relationship, or is he happy to be single? “What is most important to me is excelling at public service, and public service often has a crowding-out effect on romantic life. It can be the price of public service. I’m at ease with it. In life you have to make choices and trade-offs, and I have made my choice.”

It sounds, when he says it in that even tone, like a slightly sad, grimly made choice—after all, many people in public life have partners. Vacca hopes that Torres will find space for a personal life. “Is he a workaholic? Yes. Is he 24/7? Yes. I don’t want to intrude in his personal life, but I would love for Ritchie to meet someone. I think that would be great, and I think it will happen, whether planned or not, at a certain point.”

What does the future hold for this intelligent, telegenic, and charismatic young political star? Predictably, Torres demurred when asked to discuss his future ambitions, which—who knows—could one day include such offices as the New York City mayoralty or the presidency.

“I have a rule. I never put politics ahead of governing. I focus on governing effectively, because I’m optimistic if I excel at governing the politics will take care of itself. People will want me to rise to the next level. I never get ahead of myself and calculate 10 or 20 steps ahead. I focus on whatever role I have at any given moment.”

But looking at his assured political rise, he is surely ambitious, this reporter said. “I have moral ambition and policy ambition,” Torres responded. “I have an ambition to advocate for poor people of color in public housing. I have ambition to advocate for the essential mothers and workers of the South Bronx. And that’s where my focus is going to be on.”

That intensely held and practiced localized focus also means Torres intends to be in D.C. “as much as necessary and no longer. I am going to return home.”

For Torres, “home” seems to be a multi-faceted touchstone. It is not just where the heart is but where the wellspring of his determination to effect change, and his own ambition and self-possession, lies.

For him personally, “home” is where his mother first fought for him. For him politically, it is now his focus when fighting for others, principally the poorest people of color in his constituency. Every part of Torres’ story, personal and political, seems to begin and end there. “The Bronx is my home, always has been and always will be,” he said, as we wound up our conversation. “I have lived in the Bronx, I have suffered in the Bronx, and I will die in the Bronx.”

“It is important for an elected official to be visible and present in their home districts,” he added. “The most important lesson my mother taught me is to never forget where you come from, and to never forget the people who voted you into office. You always have to return home.”