He was the savior, the second coming of Ronald Reagan. Trumpier than Trump in ways that were good, less Trumpy than Trump when it came to late-night tweets and outlandish proposals and bromances with dictators like Kim Jong Un. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis was the dream of a Republican establishment that wanted to move beyond Trump while retaining Trump’s supporters.

Now the dream is dead, with DeSantis announcing on Sunday that he was suspending his campaign after a dismal showing in Iowa, where his vaunted door-knocking operation came up short. New Hampshire and South Carolina were not looking any friendlier. Not a candidate usually known for his self-awareness, DeSantis somehow sensed that it was time to call it quits.

The conventional wisdom is that the dream of a DeSantis presidency has merely been deferred until 2028—maybe even preserved by his decision to forego weeks of humiliation that would have culminated in a Super Tuesday trouncing. But I am not so sure. After all, the factors that doomed DeSantis in 2024 will still be around in 2028.

Primary among them is DeSantis himself. Anyone who followed him throughout his first term as governor could see that he was not made for politics any more significant than the House backbench. DeSantis disliked people on the whole; if they disagreed with him, he despised them. Even basic shows of empathy proved difficult.

In July 2020, a reporter asked the governor at a press conference regarding the coronavirus pandemic if he wanted to say a few words about the passing of Civil Rights hero John Lewis the night before. Plainly unnerved by the question, DeSantis responded with unfeeling irritation. “All right, yeah. I appreciate the question, but we’re trying to focus on the coronavirus,” he said. Several months later, the hateful conservative disk jockey Rush Limbaugh died. DeSantis promptly ordered flags across the state lowered to half-mast.

The pandemic made DeSantis famous. To his credit, he saw that closing schools and businesses was wrong and, what’s more, unscientific. He stood up to the experts, and the press. He turned out to be right in many respects.

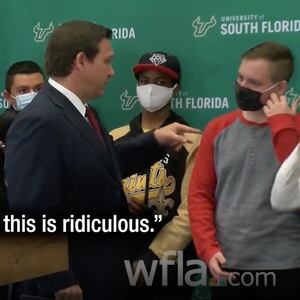

But being right only made DeSantis angrier and more self-righteous, as demonstrated when the governor held a press conference at the University of South Florida in March 2022. Some high school students were to stand behind him as he spoke. They were wearing masks. This displeased the governor. A camera captured him hectoring the students like a deranged gym teacher: “You do not have to wear those masks. I mean, please take them off. Honestly, it’s not doing anything. We’ve got to stop with this COVID theater. So if you wanna wear it, fine, but this is ridiculous.”

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis makes a campaign stop at LaBelle Winery on Jan. 17, 2024 in Derry, NH.

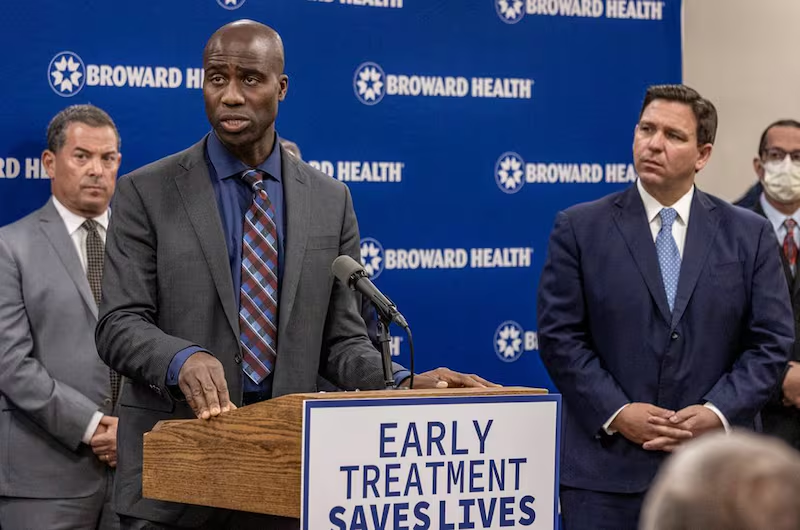

Matt McClain/The Washington Post via Getty ImagesBy then, DeSantis was smart enough to realize that the coronavirus was fading as a political wedge issue. He appointed the dangerously unqualified Dr. Joseph Ladapo as his surgeon general, thus ensuring that the anti-vaccine right would receive its steady diet of quackery. For his own part, though, DeSantis moved on, waging culture wars against Disney, the LGBTQ+ and Black communities, alienating his own constituents in hopes of winning future voters in New Hampshire and Iowa.

DeSantis justified his own authoritarianism the way Viktor Orban of Hungary may have, as a necessary bulwark against the excesses of the left. He constantly spoke about freedom, even as he erected ever more limits on what people could say or do. And he did it all with grim, humorless diligence, as if checking off boxes on some political consultant’s presidential to-do list. It is difficult to come off as both persistent and inauthentic, but DeSantis managed to pull it off.

Florida Surgeon General Joseph Ladapo, left, speaks during a press conference at Broward Health Medical Center on Jan. 3, 2022, alongside Gov. Ron DeSantis.

José A. Iglesias/Miami Herald/Tribune News Service via Getty ImagesThe DeSantis who won re-election in 2022 was not the unknown congressman who had prevailed in 2018 thanks to a Trump endorsement. But if his political identity was evolving, the underlying character remained the same. For a feature in The Atlantic, the British journalist Helen Lewis traveled across Florida, finally arriving at the second DeSantis inauguration.

At the ceremony, the Pledge of Allegiance was read by Felix Rodríguez, an 81-year-old Cuban-American who had participated in the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion 60 years before. Rodríguez had trouble with the words. Lewis observed the governor’s response:

“I realized instantly what a natural politician—Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, Ronald Reagan—would have done: walk over, take Rodríguez’s arm, and create a viral moment of human connection. DeSantis stood rigid and stern. Given a 15-hour run-up and a focus group, he might have gamed out the advantages of a small, public act of kindness. But he couldn’t get there on his own.”

Lewis was a rare skeptic during a period when fawning profiles dominated the very mainstream media DeSantis continued to insist was his enemy. Because of that stubborn insistence, DeSantis failed to capitalize on his standing as the post-Trump candidate many Republicans—and even some moderates—were yearning for in late 2022 and early 2023.

Instead of validating the hopes invested in him, DeSantis remained standoffish, the persona largely defined by an unusually aggressive Twitter operation. Maybe this was a misreading of the moment. More likely, I suspect, is that the people around him knew that the key to a successful DeSantis candidacy was to preserve DeSantis as a conservative palimpsest on which National Review could inscribe whatever fantasies it wished.

“I think it turned out that he was Ron DeSantis,” Republican strategist Liz Mair says when asked to diagnose what went wrong with his campaign. “Awkward, weird, too conservative on a host of policies, seemed like a knock off version of Trump at best and at worst like a less appealing Floridian Ted Cruz.”

Hence the disastrous campaign announcement on X with Elon Musk and venture capitalist David Sachs, a game of keepaway culminating in a glitchy event that featured the candidate ranting about his favorite topics: DEI, ESG, etc. The obscurity was the point.

And, of course, there was Trump. DeSantis’ primary political action committee was called Never Back Down; though, legally, it could not coordinate with his campaign, everyone knew it ran the show. Presumably, the tough-talking governor who took on mask-wearing high schoolers and teachers who announced their gender pronouns would be eager, even zealous, to duel the man who stood between him and the Republican presidential nomination.

President Donald Trump is greeted by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis at Southwest Florida International Airport on Oct. 16, 2020, in Fort Myers, Florida.

Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty ImagesNot exactly. Always too clever for his own good, DeSantis thought he could skirt past Trump without Trump noticing; that he could court both MAGA and suburban conservatives who read The Bulwark more than once in a while, even if they still watch Fox News; that he could tout his six-week abortion ban in Iowa while pretending he’d never signed it in New Hampshire.

“The reason DeSantis was seen as the strongest challenger, and almost certainly was the only one who ever had a path, is that his team built up a huge crescendo of hype to set the table for his entry—he just was never able to capitalize on it,” the Republican strategist Liam Donovan told me.

DeSantis kept crowing how he had “beat the left” in Florida without ever explaining how he was going to beat the Donald in Iowa. He often seemed more intent on outwitting the public, offering legalistic answers on every topic from Ukraine to Jan. 6.

“Fundamentally this was always going to be a difficult needle to thread,” Donovan says, “something that took shrewd strategy, flawless execution, and transcendent political talent to pull off.” DeSantis was flawed on all three counts, he believes. I see no obvious way to fix those flaws. He is already the self-pitying, embittered Richard Nixon of 1973; the more nuanced Nixon of the late 1960s was always too tough a role for Ron.

In 1956, Soviet premier Nikita Khruschev denounced Stalin’s “cult of personality” in a secret speech that marked a break with decades of brutal dictatorship. I don’t know what a Khruschev-like address would look like today, but I am certain that Trump will continue to maintain his grip on the Republican Party until such a condemnation comes along.

DeSantis backed down from that challenge. He “refused to throw those punches, all while letting Trump humiliate him,” says former Trump administration staffer Sarah Matthews, an unstinting critic of her former boss—and of Republicans too timid to criticize him. “Now, he's saved the ultimate humiliation for last by ending his campaign with an endorsement of Trump.”

The endorsement is as cynical as every other political move DeSantis has made since gaining national attention in 2018. By endorsing Trump now, he hopes to gain an endorsement from Trump in 2028.

“If he runs again, he’ll benefit from low expectations,” Republican strategist Alex Conant says. So that must be it, then. It’s another perfect calculation from a politician who doesn’t seem to realize that it is conviction that he lacks.