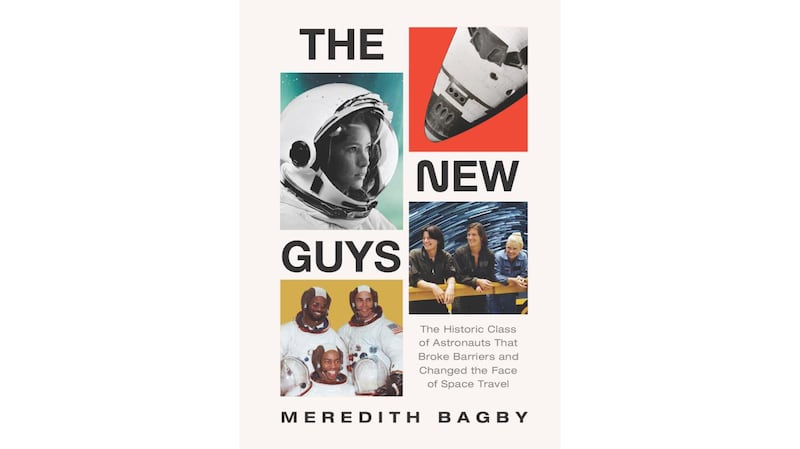

Astronaut, saxophonist, and karate black belt Ron McNair overcame an impoverished childhood in segregated Lake City, South Carolina to earn a Ph.D. in physics from MIT and become one of NASA’s first Black astronauts. Although Ron’s path to NASA was nearly derailed because of systematic racism and inequality, he found inspiration in the Black leaders around him and persevered. Tragically, Ron’s life was cut short when he died in the Challenger disaster. But his legacy lives on. In this excerpt from The New Guys by Meredith Bagby, we see how McNair stepped away from a promising career as a laser physicist for a once-in-a-lifetime chance to be an astronaut. Even though the world told him to play small, Ron was always taking risks and betting on himself. And he challenged others to do the same.

Malibu, California. Spring 1977

“What do you mean, you’re going to be an astronaut?” Carl McNair pressed the phone against his ear to make sure he heard his brother Ron correctly.

“NASA’s looking to recruit for the new space shuttle program,” Ron said. “So, I applied.”

Applied? Carl thought. “Won’t there be thousands of people applying? What makes you think NASA will choose you?”

“Why not? I have the credentials,” Ron said.

Carl shook his head and laughed. Only eleven months separated the two brothers. They had spent most of their lives in sync. No one knew Ron better than Carl. Even so, Ron could still surprise him. Sure, Ron was one of the few Black men who had earned a Ph.D. in physics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He was a star athlete in high school and college and a black belt in karate. He had recently started working as a laser physicist at Hughes Research Laboratory in Malibu, California—the very company that had invented lasers in the 1960s. If anyone’s qualified to work for NASA, Carl thought, it’s Ron. Still, an astronaut? Astronauts were “larger-than-life heroes like Neil Armstrong and John Glenn,” not little ol’ Ron McNair from Lake City, South Carolina.

Ron had grown up in the segregated South only three generations removed from slavery. Being from the “wrong side of the tracks” was more than an expression in Lake City. Actual railroad tracks separated the Black and white neighborhoods.

“We knew our place,” Carl said. The Ku Klux Klan made sure of that, threatening Black citizens they deemed “uppity,” running their preacher out of town for supporting the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and burning a cross on their Boy Scout leader’s lawn.

Ron, the second son born to father Carl Sr., a mechanic, and mother Pearl, a schoolteacher, grew up in humble surroundings. The first home he could remember did not have indoor plumbing. The roof on the old “unpainted weather-beaten frame house” leaked; an entire room was made unlivable from water damage. On rainy days, the family set out pots and pans on the floors and the furniture to catch the dripping water. On stormy nights, Ron would fall asleep to the metallic plink plink plink of raindrops striking cookware.

To help their family make ends meet, Ron and Carl, then twelve and thirteen, headed out to the fields to harvest cotton, tobacco, beans, and cucumbers. On summer break or holidays, they would wait on the side of the road at sunrise for work. “Y’all boys want to crop my ’bacca?” a passing farmer would yell out his truck window. “Yes, sir,” the boys would bellow back, climbing into the back of the pickup.

From sunrise to sunset, under the merciless South Carolina sun, Ron and Carl fell into a flow with the other tobacco croppers: Stoop, pluck, shuffle. Farmers preferred employing young folks like Ron and Carl to pick the lower leaves of their tobacco, priming the plant to grow taller, faster. The veteran croppers spurned the work. After a few hours, the boys understood why. “By midday, I felt as if someone had stuck a knife blade deep into my lower back,” said Carl. By day’s end, the boys could barely stand. The tobacco leaves were rough on the skin and harbored tiny worms that could bite. More perilous still were the rattlesnakes hiding in the loamy furrows. Picking cotton was worse. The spiny husks tore at their hands, making them bleed.

“I gained qualities in that cotton field,” Ron said. “I got tough. I learned to endure. I refuse to quit.” He observed the hard faces of the “gray-haired men and women who spent their whole lives at such labor” and knew he did not want the same fate.

Education would be his way out. By age three, Ron wad reading. By age four, his family said, “he was too smart to stay home.” Carl Sr. lied about Ron’s age to get him into kindergarten. By five, Ron was already wowing teachers, marching around school with a pencil behind his ear and a notebook in his hand. Ron flew through the material, skipped another grade, and joined his brother Carl’s class.

Some siblings might have felt competitive with their genius kid brother, but instead Ron and Carl became inseparable, bonded by a shared love of learning. “Ron inspired the rest of us,” Carl said. “We wanted to beat him, and even when we couldn’t, we wanted to close the gap.” On Saturday mornings, Ron and Carl paged through their family’s World Book Encyclopedia, dreaming about the wide world outside Lake City.

Inside Lake City, Ron and Carl studied in segregated and underfunded schools, with used textbooks, overworked teachers, and no extracurriculars. In elementary school, Ron’s teachers told him and his peers that they would have to “try twice as hard, work twice as diligently, and learn twice as much” as whites to succeed. Ron took that message to heart, ranking number one in his class and becoming a star on the school’s football team.

Inspired by Star Trek

In 1966, Ron’s interest in science was sparked with the debut of Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek. Ron never missed an episode, racing home with Carl to warm up the TV before the stroke of the hour when the show would start. They marveled that a Black woman, the beautiful and talented Nichelle Nichols, played a leading role on primetime television as Lieutenant Nyota Uhura. “As a Black woman, she had two strikes against her in our twentieth-century world,” Carl said. “But in the enlightened society of the twenty-third century, she was a high-ranking and fully capable starship officer.”

Ron followed his love of science to a high school summer program at Virginia Union University in Richmond. There, a simple question changed his life’s trajectory. “Have you ever considered pursuing a Ph.D.?” a professor asked him, after observing Ron’s capabilities. By the time Ron returned home, he had formed a grand plan. “I’m going to get a Ph.D.,” he declared.

After graduating as valedictorian at sixteen years of age, Ron followed Carl to North Carolina Agricultural and Technical (A&T) State University, one of the largest Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) in the South. He earned a bachelor’s degree in physics and, after completing a summer program at MIT, was accepted into their physics Ph.D. program. He toiled for five years in “the dungeon,” his nickname for MIT’s basement physics labs. Upon graduation, he received his job offer from Hughes Laboratories. At twenty-seven, he and his new wife, Cheryl, moved into a sun-splashed apartment in Malibu, California.

Wearing his bucket hat, jogging shorts, and athletic socks pulled all the way up to his knees, Ron took long runs on the beach. Although he would only venture ankle deep in the water, he loved the expanse of the ocean, the way it suggested the infinite. Looking out over the cliffs of Malibu at the Pacific, he was worlds away from those cold Boston winters; the hot tobacco fields were nothing more than a distant memory. Using his intelligence and determination, he had climbed his way out of poverty. He was living the dream in Malibu: a happily married, financially comfortable laser physicist.

Still, Ron felt something was missing.

Ron had grown accustomed to tackling life, not simply enjoying it. Carl noticed the restlessness: “[Ron’s] work at Hughes was exciting, but the shift into a five-day workweek routine felt like a step toward the humdrum.” “After watching him surmount one obstacle after another, I understood he couldn’t be content on the plateau. No sooner did he reach an arduous peak than he was searching the horizon for a loftier mountain to scale.”

That new challenge came in the form of a black-and-white brochure that landed in his work mailbox announcing NASA’s search for a new astronaut class. A few months later, Nichelle Nichols, the famed Lieutenant Uhura herself, appeared on a television advertisement pleading NASA’s case. Sporting a royal blue flight suit and posed in the Apollo Mission Control Center, she appealed to “the whole family of humankind, minorities and women alike. Now is the time,” she said. “This is your NASA.” Ron sat stunned, as if hit by a Star Trek phaser beam. She was talking to him.

From The New Guys)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https:/www.harpercollins.com/products/the-new-guys-meredith-bagby?uuid=6kDpHXEIydUaQPmE1123__;!!LsXw!Xhc42GYGNvUHQ22xzpRxBbkWq34PXoEwCC2I586v0p8FiBvwzp0Z07neYWOVLfs7qZSg9SRMPJ94BbxVRD_wjneFSlmIC3zLTQ$">The New Guys by Meredith Bagby. Copyright © 2023 by Meredith Bagby. Reprinted courtesy of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.