I say let’s be careful about hot takes from the U.K. election. Jeremy Corbyn was a unique nincompoop. He was never suited to be a national leader of a major political party in a major industrial democracy. He was an ineffectual backbencher and should have remained so.

So I’m not hot on the “this is a disaster for Bernie Sanders” line. The result sure isn’t good for Sanders, who still has no shortage of his own kinds of limitations. But there are differences between the two men. Sanders has been a backbencher most of his life, too, so that’s a fair point of comparison. But when Sanders did rise to the national spotlight, at least he showed he can hold his place in it. Corbyn always looked to me like he was secretly wondering why the bloody ’ell all these people are suddenly listening to me. Also, Sanders is Jewish, and is far from a knee-jerk, left-wing, oh-no-I’m-just-anti-Zionist anti-Semite of the kind one finds much more frequently on the European left than the American version.

The big debate in the U.S. on the broad left, if it even bothers to ensue, will be around the question of whether Labour lost all those white working-class constituencies to the Tories because of its confused Brexit position or its Manifesto promising big new taxes on the rich to pay for, among other things, free universities, free childcare, huge increases in health and education spending, and nationalizing the railroads.

The people on the Sanders left will insist that it was all Brexit, because that absolves the Manifesto and permits them to argue that Corbyn’s crushing defeat doesn’t mean it’s impossible to win on a far-left agenda. More mainstream types will say it was the Manifesto’s fault, and the defeat proves that people don’t want far-left solutions.

I default toward the second view, but at the same time, it seems undeniably the case, at least from what I heard them saying all night on the BBC, that many white working-class voters abandoned Labour because they were Leavers and they didn’t like Corbyn’s mixed signals. So, as much as television always wants there to be One Reason why stuff happened, life is usually more complicated than that, and I think that’s the case here.

But even if we can’t say that the Manifesto cost Corbyn those constituencies, we can obviously conclude this: It didn’t win him those constituencies either. In other words, there don’t seem to have been a whole lot of white working-class Labour voters, northern men whose great-grandfathers were there pumping their fists skyward when Ramsay MacDonald was winning elections in the 1920s and who’d been Labour all their lives, saying, “Well, I don’t like the games he’s playing on Brexit, but I like this four-day work week more than I dislike that.”

And herein, for me, lies the real lesson of this election, and the matter we in the United States broad liberal-left must reflect upon: The gulf between “the left” and “the working class” is wider than it’s ever been and just keeps getting wider, and this is a chasm American liberalism has shown no capacity to bridge.

Historically and traditionally, of course, the left and the working class were the same thing. Ever since Marx, the basic idea has been that workers would develop a certain kind of consciousness, as workers, that would bind them together and make them see that they had a common interest (higher wages, better working conditions) and a common enemy (the capitalist class). This class consciousness would be so strong as to overpower other consciousnesses: racial, ethnic, and national.

Sporadically in human history, this has actually been true. The 1930s, mostly, but also a few later times. At the same time, though, the left came to mean many other things: student movements, antiwar movements, feminist movements, environmental movements, so much else.

I won’t go through the whole recent history; I trust you know its broad strokes. In the post-Obama United States, we’re at a point where we have a resurgent left. But it’s not a working-class left. It’s a young and predominantly big city-based left built around some economic issues to be sure but also cultural and other issues. They’re pretty much two different groups.

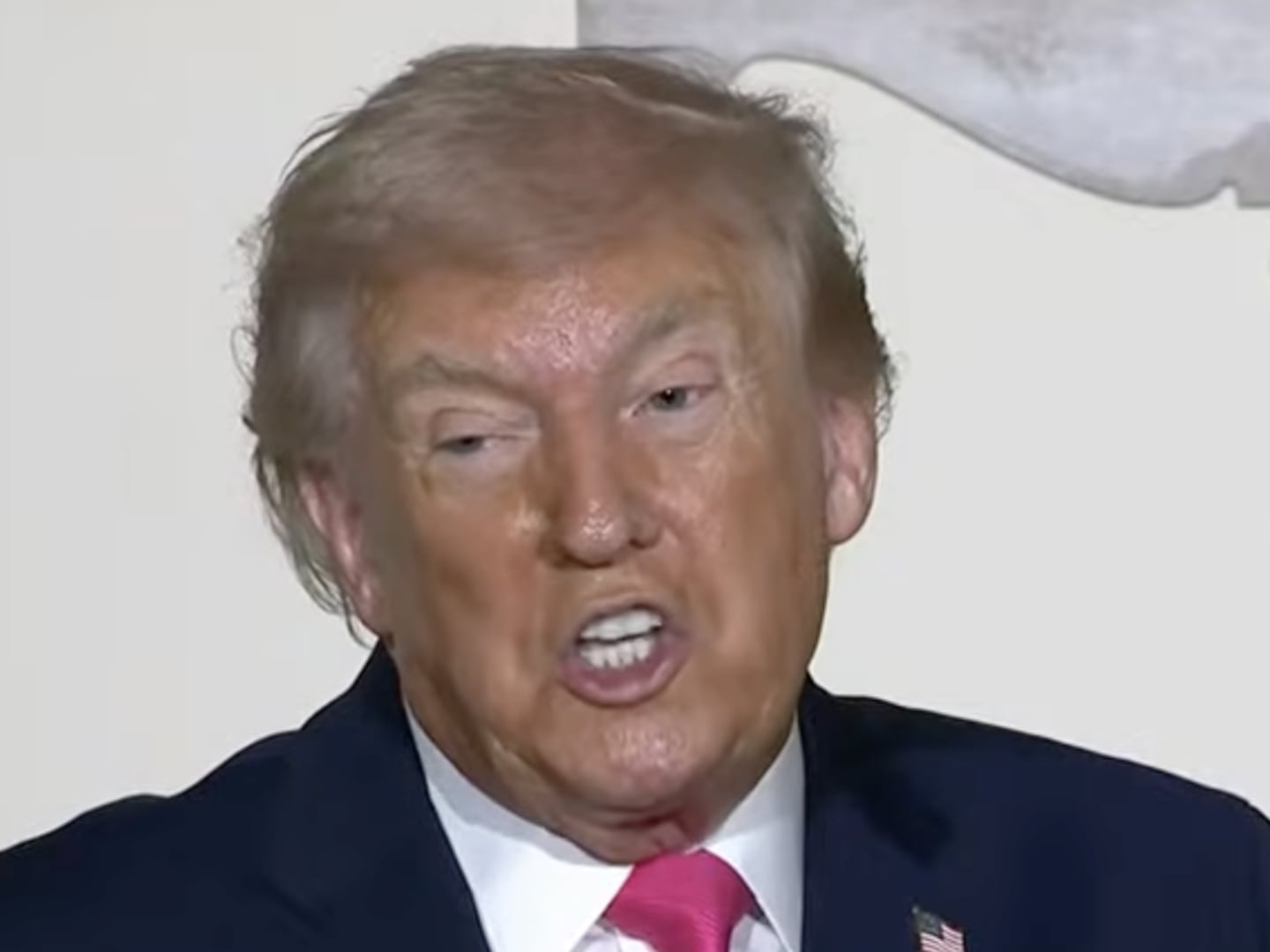

Ask yourself this question: Among Democrats, who is the candidate of the working class? It’s not Elizabeth Warren. It’s not even Sanders. If we define working class as non-college-educated, which for political purposes we do, the candidate of the working classes is Joe Biden. By a lot. And that’s just among Democrats. The real candidate of the working class in this country, alas, is Donald Trump.

In some respects, you could say that Labour yesterday finally experienced in full what the Democratic Party started experiencing in 2000. That’s when the Democrats lost the American coal fields (West Virginia went red in that election and has stayed there ever since, after backing Bill Clinton both times). The 2000 campaign, incidentally, is also when we started using “red” and “blue” as stand-ins not just for party affiliation but all manner of things—Ford vs. Volvo, iceberg v. arugula, all of that.

Still, if yesterday’s results suggest that Labour is only playing catch-up, they might also suggest that Democrats have still farther to fall among U.S. working-class whites. To my eye, none of the current candidates has what it takes to energize enough of the young left and hold enough white working-class voters. Sherrod Brown is the closest thing the party has to someone who might be able to do that—he got huge margins in the urban and industrial areas of Ohio and did far better than Hillary Clinton had two years prior in the Trumpier regions. But he’s not running.

This is all part of a broader trend across the democracies of the developed world. Right-wing ethno-culturalism is taking over everywhere, and liberalism has no good answer. (Johnson did not run a Trumpish, ethno-cultural campaign, but of course Brexit itself has always had strong overtones along those lines). Liberalism needs to develop an answer that is a hybrid of cosmopolitanism and populism. It needs, if you will, an Obama who’s more of an economic populist. When I put it that way, it doesn’t sound that hard, but, somehow, it is.