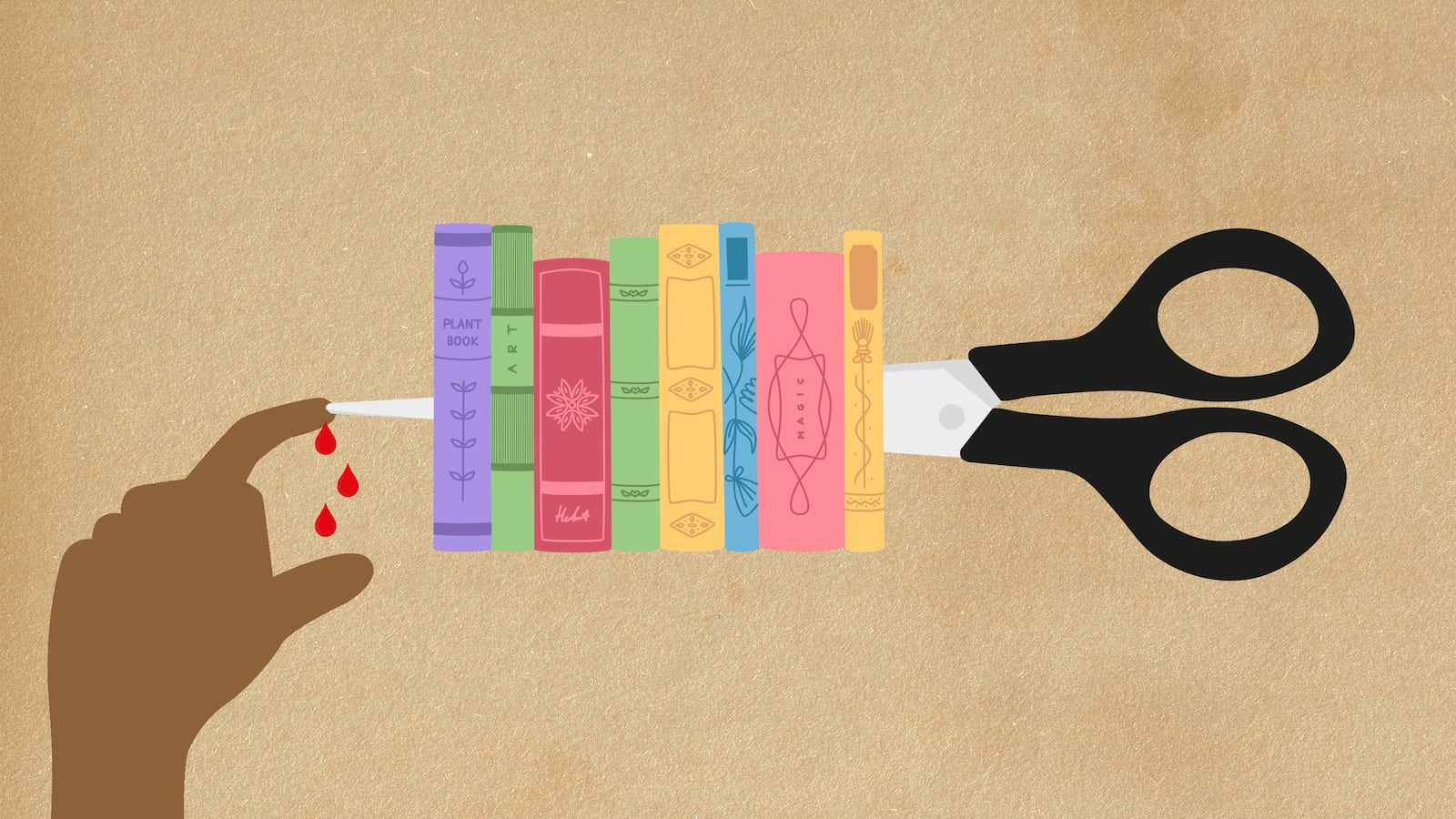

“Some minds are like soup in a poor restaurant—better left unstirred.” As Penguin-Random House endeavors to remove unacceptable prose from his and other works, this comment by P. G. Wodehouse seems an apt description of the likely outcome of attempts to sanitize and censor works moderns deem distasteful or unacceptable.

The current push among some publishers toward sensitivity reading and the removal of anything they deem offensive represents a pernicious attack not only upon free speech, but upon history itself.

There are three basic problems with this effort. First, it represents a form of intellectual laziness. Rather than working through prose we deem unpleasant due to racist, sexist, homophobic, etc. content, sanitizing old works allows us to simply avoid the issue.

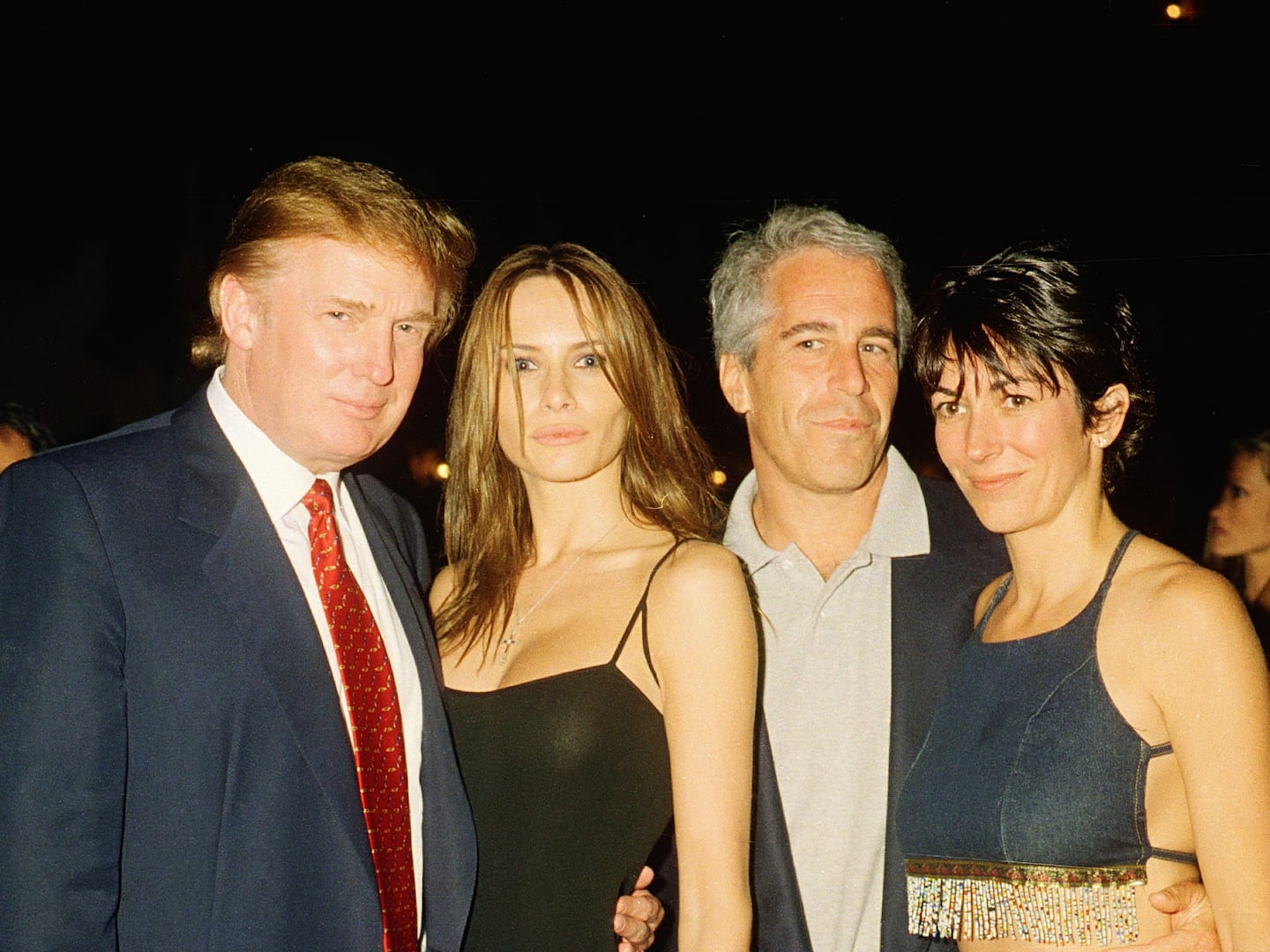

I teach a course on medical ethics and culture in which we have a segment on AI. One of the books we read is Heinlein’s The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. The book is a brilliant consideration of the rise of intelligent machines, but Heinlein’s depiction of women is sexist, to say the least, as is the dialogue he develops for the moon’s inhabitants. A sensitivity reading would suggest the need for major revisions—probably rewriting the entire book. But that’s a lazy mindset because it ignores some important questions.

Did Heinlein use sexist language as a writing strategy intended to critique sexism? Probably not. But we can also ask, is Heinlein’s prose a product of the cultural and historical context in which he wrote? There’s a good chance it is and it’s important to think about how the book reflects the time in which he wrote.

Of course, we can also ask, “was Heinlein a sexist?” The answer to this is important in interpreting the content of the book and to understanding Heinlein’s contributions to literature. These are complex questions that deserve thought and discussion about history, culture, and the intent of the author. But that thought and discussion won’t happen if the prose is sanitized to remove offensive passages.

Tied to this is a second issue of arrogance. The idea that a group of editors can make decisions on behalf of readers about what to deem offensive represents a paternalistic and condescending attitude that devalues the abilities of readers to draw their own conclusions from what they read. In essence, the attempt to sanitize works from the past is a moral effort that removes decision-making about what is right and wrong, offensive or inoffensive from the minds of readers and, instead, dictates to the public what they should think about what they read. In other words, along with deleting offensive words and passages, it erases the ability of readers to act as moral agents.

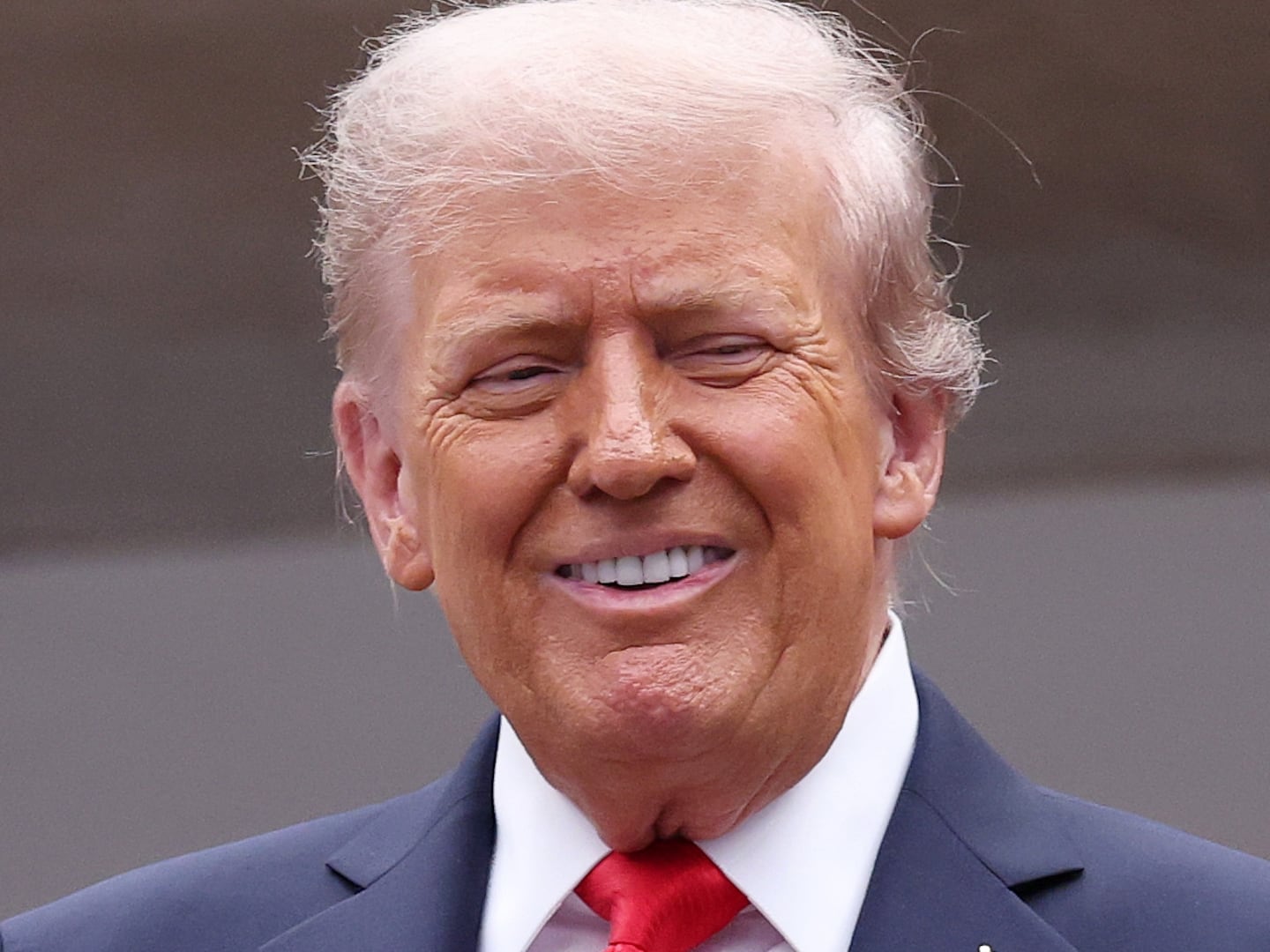

One might imagine that these problems alone would be enough to pause anyone thinking about sanitizing writings of the past, but there is a far more serious issue that needs to be considered. Imagine for a moment that you are living 50 or 100 years in the future. Masterpieces of 20th-century literature like Wodehouse’s The Inimitable Jeeves or Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory have been excised of sexist and racist content. People download them on their Kindles and read away.

What will they think? The answer is easy. They will have no inkling that the authors of those or other books may have harbored sexist, homophobic, or racist inclinations. It’s quite possible that readers will think things like, “It’s amazing how forward-thinking authors were in those days.”

I suppose publishers could put warning labels on book covers to address this problem. Something like: PUBLISHER’S WARNING: This book has been rewritten to protect readers from discomfort and critical thinking. But that won’t solve anything, because sanitizing those books only opens the door to revising the reality of those who wrote them and closes the door on both individual and collective thinking about who those authors were and why they held ideas that we, today, deem offensive.

This is bad enough, but there is a deeper issue here. Those books sanitized today will become the accepted representations of history tomorrow. Revising the prose also revises the history, because as people in the future read it is unlikely they will be aware of the types of language that was used and the bigoted ideas that were commonplace.

There is no difference between removing offensive language from the works of authors like Wodehouse and Dahl and removing references to slavery and racism from history books. Both lead to the same conclusion—whether intentional or unintentional—the dissemination of a revised history that has been sanitized, so that we do not need to individually or collectively confront the errors and evils of our ancestors.

Publishers like Penguin are engaging in a misguided attempt to do something that seems like a good idea—make literature less offensive to many who read it. However, despite good intentions, these publishers are doing a disservice to the very thing they want to support—the elimination of bigotry.

If one thinks toward the future, there is a good chance that the works sterilized today will simply become the unquestioned works those authors wrote. There will be no need for critically examining their writings or their world because it will be taken at face value that the prose people read is the prose the authors wrote. It will become the truth of who they were as authors and what their world was like.

Publishers need to be protectors of free speech, including speech we dislike or find offensive. And they need to stop, immediately, efforts to cleanse the prose of authors of the past, to ensure that future readers understand and can critically examine the perspectives and personalities of those authors—as well as the times in which they lived.

If publishers like Penguin continue on their current path, it will only ensure that future minds are left unstirred.