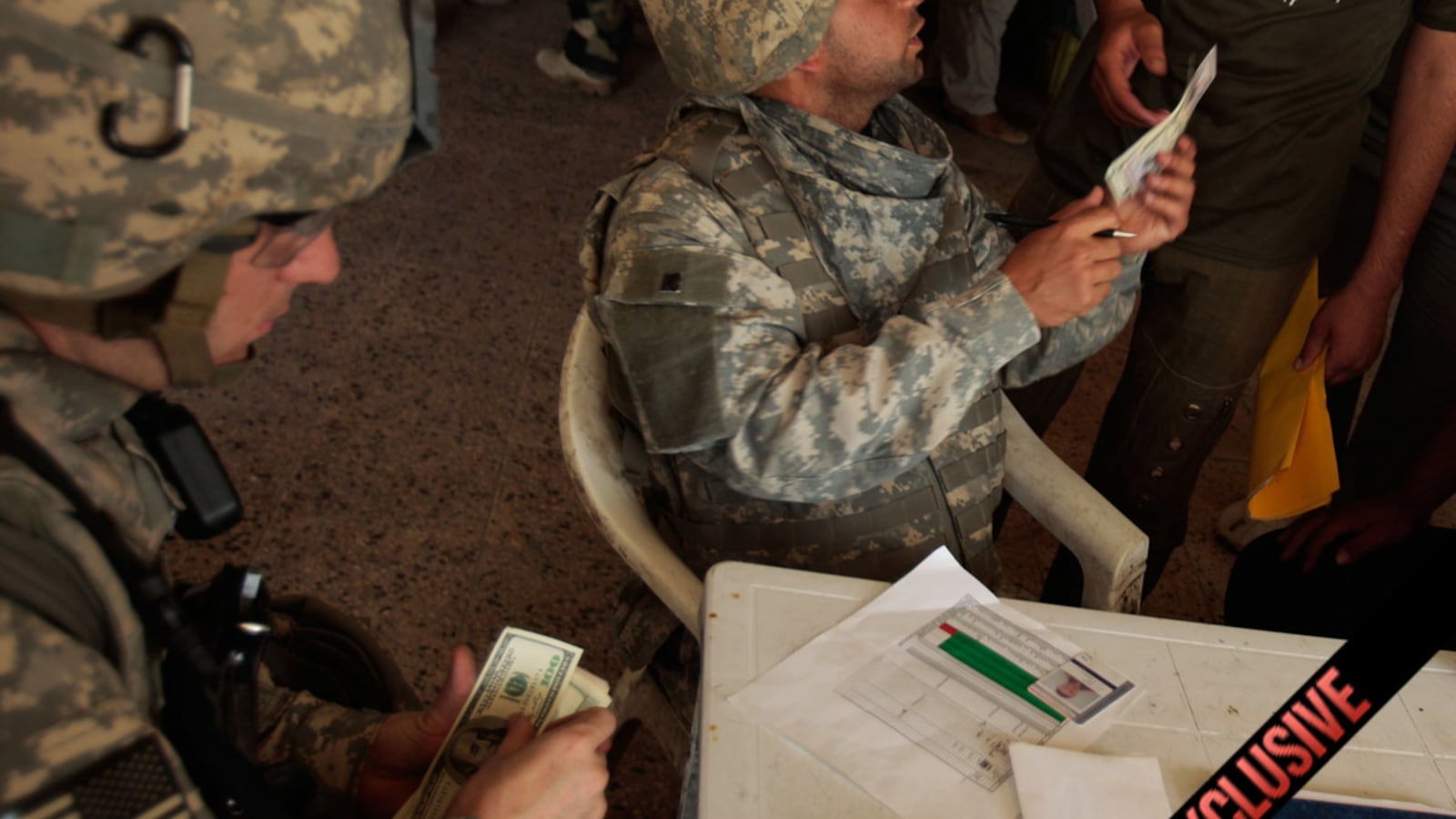

During the war in Iraq, battalion commanders were allocated packets of $100 bills and authorized to use them for anything from repairing a schoolhouse to paying off ex-rebels and paying blood money to the families of innocents killed by U.S. forces. But a new audit finds that in some cases that cash made its way to the pockets of the very insurgents the United States was trying to fight.

The money was part of the Commander’s Emergency Response Program (CERP), and from 2004 to 2011 the U.S. government poured $4 billion into it in Iraq. And because the Pentagon gauged CERP a success, a similar initiative is under way in Afghanistan. “We think CERP is an absolutely critical and flexible counterinsurgency tool,” Michele Flournoy, who was then undersecretary of defense for policy, told the Senate Armed Services Committee in 2010.

But was CERP really a success in Iraq? A 2012 audit conducted by the Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction (SIGIR) and released to the public on Monday found that 76 percent of the battalion commanders surveyed believed at least some of the CERP funds had been lost to fraud and corruption. “Commanders sometimes perceived the corruption as simply a price of doing business in Iraqi culture and others perceived it as presenting a significant impediment to U.S. goals,” the report says. “Several asserted that reconstruction money may have ended up in the hands of insurgents.”

The audit goes on to quote one commander who served in Kirkuk saying the government of Iraq “would get a cut of the CERP funding directly from the contractor. CERP contractors understood the system. This type of corruption needs to be compared with funding that was reinvested in insurgent activity or paid to disgruntled leaders of communities susceptible to insurgent support. The first is commonplace and expected, the second makes money a weapon system—given to insurgents.”

The evidence in the report is mainly anecdotal, as it is nearly impossible to account for cash in a war zone. Nonetheless, the report is detailed evidence that at least a portion of CERP in Iraq may have fed the insurgency these funds were aimed at stopping.

Marisa Sullivan, deputy director of the Institute for the Study of War and the former staff historian for Gen. Ray Odierno, who commanded forces in Iraq until August 2011, said the military should learn from the times that CERP failed. “But the benefits outweigh the costs here,” she said. “You had real, pressing needs in a battalion’s area of responsibility that could not be addressed by the longer-term development projects. Moreover, you had a security environment that prevented economic development from taking root.”

Sullivan asserted that CERP helped put people to work who would otherwise be susceptible to joining the insurgency and that the economic development the funds helped spark was critical in bringing security to the local environment. “Without CERP there would be not the kind of counterinsurgency success we saw in Iraq during and after the surge,” she said.

In some ways, battalion commanders in Iraq and Afghanistan face a catch-22 in introducing untraceable cash to the battlefield. Because it is a war and there is no security, big construction projects will require some form of protection, and that protection money often ends up in the hands of insurgents.

One U.S. Army Corps of Engineers officer told the auditors there would often be only one bid on local improvement projects. “We felt that these contractors were doing one or all of the following,” this officer said. “Conspiring with the insurgency, threatening other contractors, or paying the insurgents to allow them to work in the area.” This officer worked in Iraq in 2004 and 2005, before the military adopted the counterinsurgency strategy in 2007.

At the same time, those kinds of projects are great ways of taking young men who could join the insurgency off the streets, CERP’s defenders believe. The improvements to the standard of living also provide concrete proof the military is on the side of the local population.

Andrew Exum, a senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, said there is some evidence to suggest that CERP helped the counterinsurgency in Iraq. But that does not guarantee it could work Afghanistan.

“Money is not neutral, any more than U.S. soldiers are neutral,” Exum said. “You are always creating winners and losers with money on the battlefield."