Author's Note: Since this piece was published a cluster of academics have dissected the initial Scientific Reports article and questioned its credibility. Bioarcheologists Megan Perry and Chris Stantis criticized the presentation of the biological remains; Matthew Boulanger expressed concerns about the C-14 radiocarbon date reported in the study; microbiologist Elizabeth Bik expressed concerns about the use of edited images in Nature; and physicist Mark Boslough described the analysis as “riddled with errors.” Together with archeologist Austin “Chad" Hill, Anthropologists Morag Kersel and Meredith Chesson published a detailed examination of the study and its ramifications for looting in the region in Sapiens magazine. The evidence supplied by these scholars is compelling and suggests that the Scientific Reports article on which this report is based not only erodes scientific integrity, it also leads to the destruction of archeological sites.

If the hand of God were to reach out and smite people, then it might look a lot like a meteor. Or at least if a meteor was to smite the earth, then people might think that it was the hand of God. This is the argument of a paper published this week in the prestigious science journal Nature. Studying the effects of a meteor that devastated part of Jordan valley some 3,600 years ago, the authors suggest that it was this cosmic event that gave rise to the Sodom and Gomorrah story.

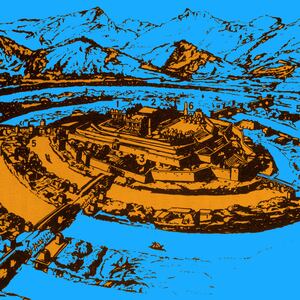

The excavations in question took place at Tall el-Hammam, the largest archaeological site in the Jordan Valley. The site was unearthed as workers quarried for gravel and has been excavated ever since by a joint team from Trinity Southwest University and the Department of Antiquities of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. What the team discovered was that while the region was continuously inhabited for two and a half millennia, 3,600 years ago it was suddenly destroyed.

What happened there can be deduced from material evidence. Archaeologist Christopher Moore, one of the authors of the study, writes: “Air temperatures rapidly rose above 3,600 degrees Fahrenheit… Clothing and wood immediately burst into flames. Swords, spears, mudbricks and pottery began to melt. Almost immediately, the entire city was on fire…Some seconds later, a massive shockwave smashed into the city… deadly winds ripped through the city, demolishing every building... None of the 8,000 people or any animals within the city survived—their bodies were torn apart and their bones blasted into small fragments.”

The extreme temperatures that melted pottery, mudbricks, and metal could not have been caused by war or even a volcano. Instead, the archaeologists argue, the area was leveled by a small asteroid, similar in size to the one that devastated Tunguska, Russia in 1908. The asteroid would either have impacted the area or detonated in the air (an airburst). The smoking gun for the theory is the presence of microscopic diamonoids in the destruction layer. These could only have been caused by the extreme pressure and heat of an extraterrestrial fireball. The scientific evidence for the destruction of the area by an asteroid impact or airburst is conclusive.

The archaeologists go on to suggest that the memory of the asteroid’s devastation is preserved in the pages of history’s most famous book: the Bible. As most Sunday school attendees know, the book of Genesis describes the destruction of two legendary Dead Sea region urban settlements, Sodom and Gomorrah. The cities had a reputation for wickedness. According to the Bible “the outcry against them before the Lord has become so great,” that God sent two angels to destroy them. Upon arrival, the angels were planning to spend the night in the city square, but Lot, the nephew of Abraham, takes an interest in them and welcomes them into his house as guests.

The city’s residents are curious, they crowd around Lot’s door and demand that he hand the disguised angels over so that they can “know” (i.e. rape) them. God blinds the would-be attackers, so they are unable to storm Lot’s house. The following morning and at the instruction of the angels, Lot and his extended family make a quick exit and “Sulphur and fire” rain down on the two cities. Sodom and Gomorroah are destroyed. Centuries of interpretation have understood the story to be a narrative about God’s condemnation of homosexuality.

Though it’s unclear why the angels needed to visit the city in person to exercise a surgical celestial attack, fire from heaven does sound like a layperson’s description of a meteor. The new study proposes that “an eyewitness description of this 3,600-year-old catastrophic event” may have been passed down in oral tradition and was eventually inscribed into biblical history.

For those who want their Bible and science to align, this would seem like a win. In this reading, the Biblical authors didn’t invent this story. Instead, Genesis contains an eyewitness report of geological events that were passed down from generation to generation. For those hoping that the asteroid explanation deals a fatal blow to homophobic readings of the story, I am sorry to disappoint. Theologically speaking, it is perfectly possibly for God to work through nature, even natural disasters. God may be supernatural but that doesn’t mean (for Christians at least) that God must act outside of nature.

The real problem with traditional readings of the Sodom and Gomorrah story is that it misses the point of the whole story and obscures the variety of forms of sexual violence that make cameos in the account. The exchange between Lot and the inhabitants is darker than the traditional reading admits. In Genesis, Lot’s concern is that the locals are treating two strangers poorly; by threatening the angels they are breaking the cultural norms that governed hospitality and the treatment of outsiders. This was a grave social crime.

Lot’s response to their conduct is to offer the mob his two virgin daughters to abuse instead. He feels empowered to do this because they are his daughters and, thus, according to the ancient view, his property. There’s no judgment in the story about Lot’s proposal to pimp out his children. Three millennia of interpretation has breezed past the violence of Lot’s solution in order to focus on homosexuality. That the crowd declines his offer of the girls and threatens to rape Lot instead does not make this a story about homosexuality, it only confirms that this is a story about sexual violence and power. In no reading are the sexual interactions figured in this story consensual. Perhaps that should have always been our focus.

Overlooking the mistreatment of women in the Bible isn’t an isolated affair: a remarkably similar story takes places in Judges 19. A Levite arrives in a foreign city with his enslaved concubine and is offered shelter. The locals threaten to rape the man and his host offers his virgin daughter and the Levite’s concubine to the rabble instead. In the end, only the concubine is pushed out of the door to the angry crowd. She is gang raped throughout the night and finds her way back to their lodging only to die at the threshold. In the morning the Levite, her slaveholder, finds her lying outside and callously tells her to get up so they can leave. Even without knowing that she is dead there is no acknowledgement of her trauma.

The people of the city are eventually punished but the Levite and Lot aren’t condemned for their cowardly willingness to sacrifice vulnerable women to protect themselves. Nor is violence against women enshrined in interpretive tradition as a crime against God. As Jennifer Barry, an associate professor at the University of Mary Washington and expert in the history of sexual violence told me, “in stories like Sodom and Gomorrah and Judges 19, the sexual violence preserved in the text focuses on the protection of men, while casually handing over women (some of whom are never heard from again).”

Scientific explanations for the destruction of the city certainly don’t solve the ethical problems that surround sexual violence in the Bible, but we might wonder if they are necessary at all. Jon Marks, a professor of anthropology at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte, told The Daily Beast that “The archaeology [in this study] is great, but trying to link up random possibly real events with ancient stories is a pretty silly expenditure of mental energy.” If the writers of the Bible had thought that Sodom and Gomorrah were devastated by space debris rather than divine punishment, the story would not be in the Bible. It’s precisely because of the ethically problematic reading of divine judgment that it’s in the text to begin with.