Andy Warhol was a figure in my New York landscape well before we met and some early sightings seem fresh as yesterday—Andy Kaufman’s breakthrough night at Carnegie Hall in 1979 being one.

This began with the comedian performing an Elvis Presley song, and then another, another, another, and another, which was when I saw Warhol making for the exit.

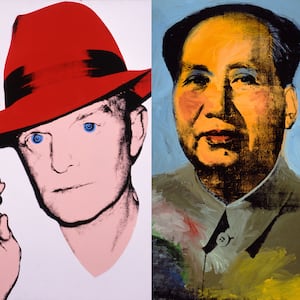

Had the multiple Elvises underwhelmed the master of serial celebrity, who had himself made images of multiple Elvises? Or was he just off to a more promising party?

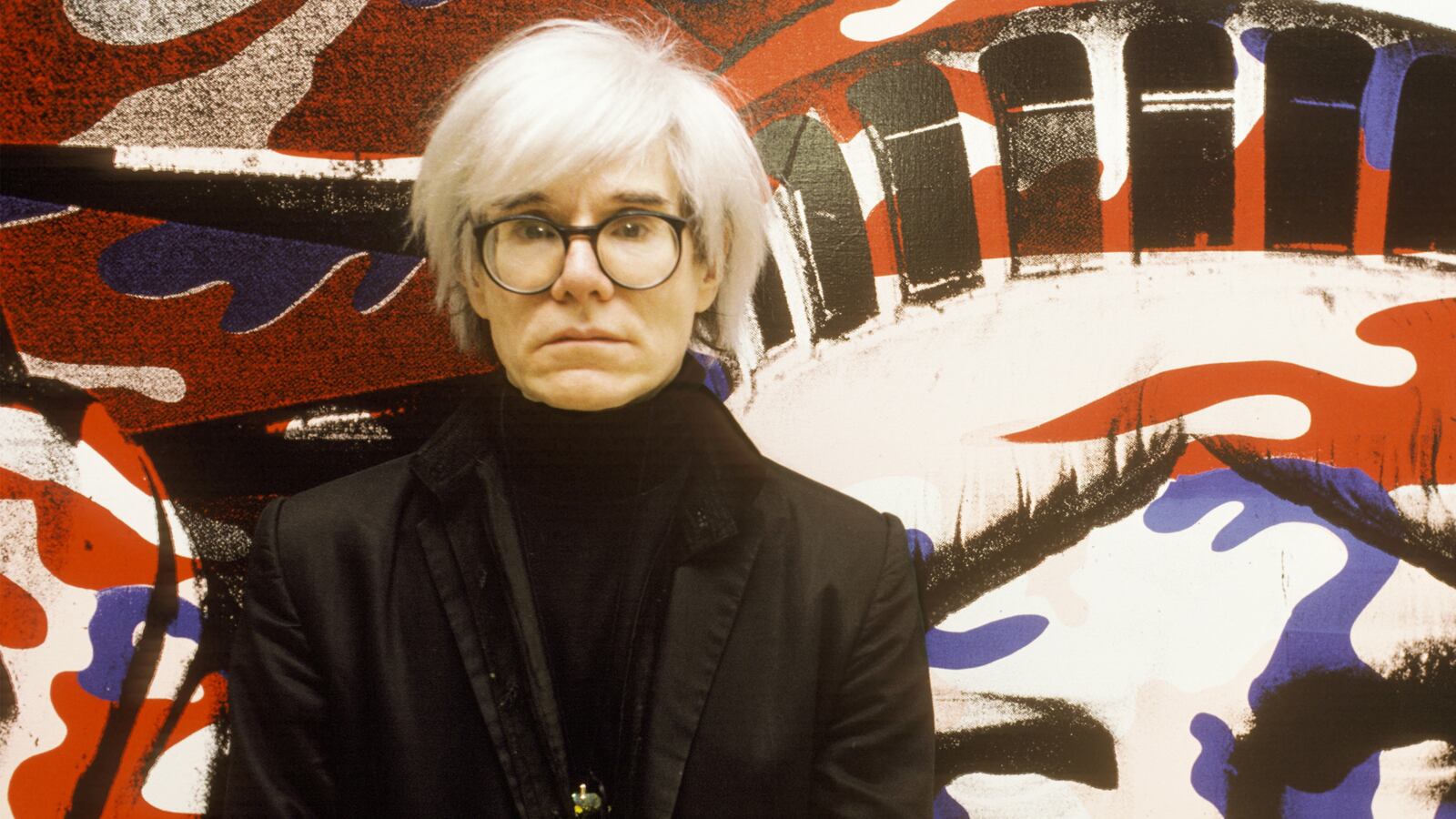

The social and artistic selves of Warhol recurred to me as I walked around the Whitney Museum’s blockbuster exhibition Andy Warhol—From A to B to Back Again, which The Daily Beast’s Tim Teeman reviewed last week.

Such was Warhol’s ubiquity that it was no surprise in 1982 to see him on a catwalk, modeling for the fashion house Van Laack. The owners, Rolf Hoffmann and his wife, Erika, were collectors, and Erika told an interviewer that Warhol had treated the gig as more than a flashbulb moment, that he had contrived to have his photograph and measurements appear in the catalogue of the Elite model agency.

“We had to hire, to brief, and to treat him exactly like the female models, including payment,” she said. “On the catwalk, he was smaller and much shyer than his radiant female colleagues, seriously focused to pose and perform. Amidst the TV glamour, the flashes, and the music, that was a touching moment.”

Andy Warhol (1928–1987), ‘Christine Jorgenson,’ 1956. Collaged metal leaf and embossed foil with ink on paper, 13 x 16 in. (32.9 x 40.7 cm). Sammlung Froehlich, Leinfelden-Echterdingen, Germany.

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS) New YorkThe upper art world, though, tended to be less warmed by Warhol’s professionalism than chilled by his media fixation and put off by a cross-cultural reach that took in art, movies, TV, publishing, briefly managing The Velvet Underground, designing album covers, and endorsing Puerto Rican rum, stereo equipment, and an investment bank while wearing a fright wig.

At Max’s Kansas City, the art world boîte of choice of the period, heavy hitters like Donald Judd, Robert Smithson, and John Chamberlain drank and disputed in the front room while the Warhol troupe occupied a room to the rear. Ruth Kligman, Jackson Pollock’s former mistress, told me that when she tried to introduce Mark Rothko to Warhol, he turned his back on them.

No wonder Warhol once said the only artist he enjoyed being with was Leroy Neiman, an artist who was wildly popular rather than Pop, best-known for his sports illustrations for Playboy. It had been one of the black marks against Warhol on the upper art world checklist that he had agreed to be in a double show with Neiman at the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art.

The botched assassination of Warhol by Valerie Solanas in 1968 happened because he wouldn’t return a script she had written brought about radical changes.

“He stopped going to Max’s after he was shot,” says Anton Perich, the photographer. “All his Superstars were waiting for him. It was like Waiting for Godot.”

“When he was shot the whole atmosphere was different,” Taylor Mead told me a few years ago over drinks at Cipriani Downtown with Ultra Violet (both have since died). Both had been key members of the Factory’s inner core and both had appeared in numerous Warhol movies, Ultra Violet having been a Salvador Dalí muse before Warhol anointed her a Superstar.

“After that he hired the upper class to work with him,” Mead said, meaning folk like Edie Sedgwick, an heiress, and Anne Lambton, the daughter of a British peer. “The eccentrics, like Ultra and me, were thrown out of the window. Without parachutes.” A long-standing grievance surfaced. “He owed me 50 bucks when I was starving to death in Spain and he wouldn’t send it to me,” Mead said.

Lambton said of Warhol, “He was like an idiot savant, amazingly astute and funny. People thought he was vacuous, but I didn’t. He was the perfect companion for a sheltered young girl. We had good jokes.”

I got to know Warhol a bit myself, well enough that I sometimes found myself talking with the slyly observant author of Popism, not the Warhol so frequently described as being restricted to “Wows!” and “Gee, greats!”

Furthermore I had liked him. The response of old Factory malcontents when I told them that, though, would usually be on the lines of, “Well, you didn’t know him very well, did you?”

Their durable bitterness was often centered on their role in giving Warhol key ideas. “Andy never did a painting, Andy never wrote a book, Andy never made a film,” Ultra Violet said. “That is where his genius lies.”

Andy Warhol (1928–1987), ‘Self-Portrait,’ 1964. Acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen, 20 x 16 in. (50.8 x 40.6 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago; gift of Edlis/Neeson Collection, 2015.126.

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS) New YorkWell, I said, wherever the ideas came from, he put together a pretty strong body of work. I added that I felt he had heart.

“Can you elaborate on that?” Ultra Violet asked, silkily.

Taylor Mead cackled.

The conversation moved on to Warhol’s first trip to California in 1962, which was occasioned by his second show at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles, but which was also motivated by his desire to move on from cheaply made conceptual movies into “real” big budget movie-making,

“He said he wanted to be part of the American myth,” Ultra Violet said. “And in many ways that’s Hollywood.”

Fame, part of the Hollywood work product, is at the heart of the Warhol oeuvre. “When he went into hospital he asked who is famous here?” Ultra Violet said of Warhol’s going into New York Hospital for a gall bladder operation in 1987. “That was all he cared for. They said, ‘Mr. Warhol, you are the only one famous.’”

Taylor Mead wasn’t having that. “With Andy it was always sort of a joke about how famous he was,” he said.

“But you can cash in on fame,” said Ultra Violet firmly.

Warhol died in 1987 aged 58, and now Taylor Mead and Ultra Violet are gone too.

David McGough was a celebrity photographer when he met Warhol. “We would talk at least once a week. In the street or at a party,” he said. “And it was almost like you were talking to a fan. He just wanted to know who was around and who was with who.”

The actress Pia Zadora hired McGough to document Warhol making her portrait. “I got to spend the day in the Factory,” he said. “I was having Andy do all kind of pictures up there and he was so happy.” Soon enough, he ran into Warhol at a party. “Oh, you know I’d really love to do something with your pictures,” Warhol said.

McGough’s work had already appeared in Interview and he didn’t feel that’s what was meant.

“He had taken a Madonna picture of mine and doodled on it with Keith Haring. It’s pretty cool, what they did. They gave it to her for a wedding gift when she married Sean Penn. So I’m really not sure what he had in mind but I was really thrilled because I had been waiting for a long time to work with him on any level. I was so in awe of him.”

He would never know. Warhol died soon after.

Gerard Malanga was Warhol’s right-hand man between 1963 and 1970, a fertile time both in art and movie-making.

Malanga went with him to see Jean-Luc Godard’s masterwork, Alphaville, during a trip to Paris.

“Neither Andy nor I spoke French and there were no subtitles,” he said. “When we walked out Andy was complaining…”—he affected a Warholian whine—“Oh, Godard’s copying me! I said stop it! That’s total nonsense! Andy had only been making movies for less than two years when we saw Alphaville. It was like talking to a little kid.”

I brought up Taylor Mead’s $50 woe. “I remember that episode,” Malanga said. “Taylor was in the hospital because he got mugged. I felt bad for him. But it wasn’t like Andy was cheap. It was like the most mundane things could be such an effort to Andy. And this was what got him stabbed. Because Valerie got paranoid that he was going to steal her script and make a movie of it, right?

Andy Warhol (1928–1987), ‘Flowers,’ 1964. Fluorescent paint and silkscreen ink on linen, 24 x 24 in. (61 x 61 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago; gift of Edlis/Neeson Collection, 2015.123.

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York“All Andy had to do was put it in an envelope, put a stamp on the envelope, and mail it back. But it was like a chore that he just couldn’t do. Same thing with Taylor. Andy could be frugal. And he could also be very generous. But little mundane things like that…”

Malanga moved on to concentrate on his photography in 1970. It had been he who brought Paul Morrissey aboard. Morrissey’s beat was the movies and he was sour about much else, including the very Factory itself.

Concerning a book about Warhol’s screen tests, he complained to me that it was full of what he termed euphemisms. “Like ‘Factory technicians.’ There was no such thing. There was nobody there who did anything but me,” he said, adding that the book was “a product of what I call the Warhol Military Industrial Complex. It’s based on a fantasy of what they think Andy was.”

In 1972 Warhol hired Ronnie Cutrone, a young artist, as his assistant. “I mixed the colors for the paint, I stretched the canvases, I did the collages,” he said. “They used to call me the head of the art department as a joke. Because it was just me.” He worked on all the major series, including the Oxidation works, aka the “Piss” paintings, abstractions created by urinating on copper sulphate.

Warhol had been having problems getting the color bright enough in these, and Cutrone proposed they take Vitamin B Complex to up their acidity.

“Andy said great! So I went out and got a big bottle of Vitamin B Plus. And then we would have coffee, water, and maybe orange juice every morning. But Andy and I were both shy. We couldn’t pee in front of each other. We had to do it separately. And it would come out literally like Dayglo. They were so vivid after that.”

The Piss paintings were produced between 1977 and 1979 and sold poorly. Warhol, who was usually able to brush off sniping, was wounded by “The Rise of Andy Warhol,” an eviscerating New York Review of Books cover story by Robert Hughes that came out on Feb. 18, 1982, and described him as “the first American artist to whose career publicity was truly intrinsic.”

Warhol’s market had begun to droop and remained on the skids until a decade after his death.

Cutrone left the Factory in 1980 to focus on his own art but he remained a Warhol loyalist. I spoke to him a few years back and he was still angered by the disrespect shown for Warhol’s later work.

“He couldn’t get more than $50,000 for a painting,” he told me. “It was pathetic. Other artists who weren’t nearly as good as he was were getting two hundred and fifty, four hundred and fifty thousand for each canvas. And Andy would never even get the fifty, there would be a big discount. So he might get 35,000 top dollar for his art. Which I found to be a travesty.”

A few dealers supported Warhol. His connection with Alexander Iolas, the Greek-born dealer who had given him his first gallery show, endured. Iolas sold pieces to European collectors and in 1984, he commissioned a major group of works from Warhol based on da Vinci’s painting “The Last Supper,” one of which you will see at the Whitney.

Another supportive dealer was Larry Gagosian, then a relative newcomer to New York City’s Chelsea art scene, who had been taken to see Warhol by his longtime lieutenant, Fred Hughes.

“He let me come to the studio, you know, the Factory,” Gagosian says. “And I started selling Warhol paintings out of the studio. With Andy there. Under Andy, while Andy was around. And we were having lunch there one day with Fred, in his office. And I saw these things rolled up. I didn’t know what they were, they were kind of gold-colored, copper-colored. They looked like rugs, they were rolled up and wrapped in plastic.

“I said, ‘What are those?’ And Andy says, ‘Oh, those are these Piss paintings. Nobody wants them.’ He kind of dismisses them. And I said, ‘I’m kind of curious to see them. Can I see one?’ So we, literally, Andy and me and Fred, unrolled a 30-foot Piss painting, out on the floor.

“I said, ‘Wow! This is really cool! I mean I really like this.’ And then Andy—I remember exactly what Andy says—he says, ‘Do you think you could sell them?’

“And I said, ‘Sure! Absolutely! Why not? Let’s do it!’ So I said, ‘Let’s do a show.’ And he went along with it. And we had an opening. And we had a party afterwards at Nell’s on 14th.” (Nell’s, a basement restaurant, was then piping hot.)

That was Warhol’s last show during his lifetime. His market remained stagnant for 10 years after his death. Now? Warhol is huge and, as in those early Factory years, as much so outside the art world as within it.

After the recent screening of Matt Tyrnauer’s documentary Studio 54, there was an onstage interview with Ian Schrager, a co-owner of the club. And what was his very first question? A man in the audience asked what he had thought of Andy Warhol. “He was a sphinx,” Schrager said.

Valerie Solanas once said that talking with Warhol was “like talking to a chair.” Go to the Whitney. The place is pulsing, alive. The sphinx—or the chair, if you like—has done OK.